What Do We Mourn? : Shoebox and the Death of the Single-Screen Theatre

Elegies for the single-screen theatre have been pouring in from different corners of India, especially over the last several months. A long and hopeless struggle to compete with multiplexes seems to be drawing to a close, catalysed by the two devastating waves of the pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns. Many people with access to stable internet connections, which often come with complimentary OTT subscriptions, have taken to watching films almost exclusively on online platforms. Even a return to the multiplex feels like a nostalgia trip.

.jpg)

Palace Theatre.

.jpg)

Ticket Ghar.

This is the hour of the archivist, when the act of collecting the debris of history conflates with mourning. Some, like Hemant Chaturvedi—who had travelled 32,000 kilometres across India documenting over 600 single-screen theatres between January 2019 and March 2020—gesture movingly towards the architectural and anthropological legacies of the theatres through their photographs. Others like Immersive Trails, alongside reproducing 360-degree views of the interiors, have been trying to collaborate with owners to find sustainable ways of preserving the edifices. But what is the point of holding on to the past?

Faraz Ali’s debut feature, Shoebox, co-written by him and Noopur Sinha and produced by Faraz Khan, bravely resists answering this question in absolute favour of the nostalgist. Premiering at the Dharamshala International Film Festival in 2021, this beautifully paced film traces through the eyes of Mampu (Amrita Bagchi), her father, Madhav’s (Purnendu Bhattacharya) desire to protect his single-screen theatre in Allahabad against property developers. At the moment of her return from Pune—where she is pursuing her doctoral degree—the city itself is undergoing an identity crisis as its inhabitants are divided into two camps. On the one hand, there are those who favour the change of its name to Prayagraj and the accompanying promise of progress and development spun by the right-wing fundamentalist government, and on the other, are those who see through the reckless opportunism of this narrative. The city is gearing up for the Kumbhmela and real estate—even on the fairground—is being fought for tooth-and-nail.

Preparations for the Kumbhmela.

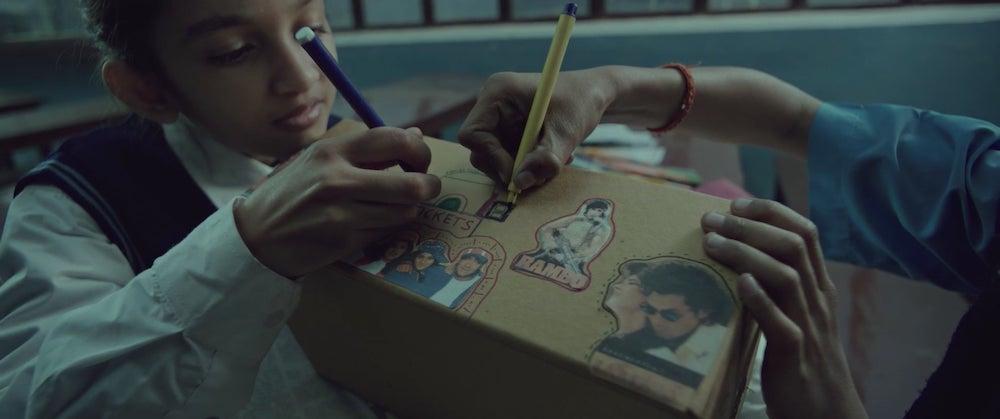

Like Marcel Proust’s madeleine, the portkey that allows entry into the protagonist’s memories in this film is a shoebox, which Mampu rediscovers inside her father’s cupboard while rummaging for some documents after he is admitted to a hospital. It is the same box that had contained Madhav’s gift to his wife on Saraswati puja many years back, on the fateful day she tragically died in a car crash; the same box that Mampu and her friend Kaustabh would later turn into a toy projector for a school assignment in order to illustrate the rectilinear propagation of light. They were barely into the first few frames of a rejected length of film reel from her father’s theatre—seemingly of a film featuring Amitabh Bachchan—when Madhav interrupted their under-the-table screening and snatched away the makeshift projector with a stern word against watching films. A strange contradiction, for a man so enamoured of the screen? Perhaps not.

Mampu and Kaustabh making their projector.

In subtle ways, the film makes us aware of Madhav’s self-positioning within a changing world. He hails from a Bengali, upper-caste family (Chatterjee), the likes of whom—often employed in government positions—seem to have migrated to the erstwhile Upper Provinces in the wake of 1857 as the British tried to quell dissent through civil administration. Madhav is outraged that politicians and developers view his theatre as “property,” oblivious to the value he sees in it as a space of collective and lived memory. While it is evident that the theatre has not been run profitably in ages, Ali’s empathetic portrait of Madhav ensures that his vulnerabilities—as a widower, father and older brother—are conveyed alongside his social and cultural hubris. Perhaps his reluctance to allow his daughter to enjoy screenings at the theatre stems from the same positioning, which perceives a class hierarchy between the proprietor and the clientele, with the additional factor of gender.

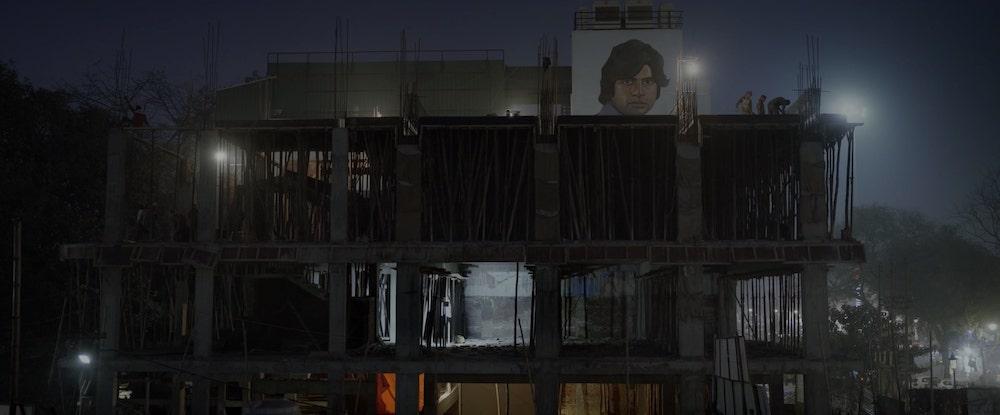

Amitabh Bachchan, as a working-class cult hero, gradually erased.

What could easily have been represented as a reductive debate between historical sensitivity and callous urban development turns into a nuanced and deeply personal story of Mampu’s attempt to navigate patriarchy, her family’s legacy in Allahabad and her eventual search for justice (no spoilers). One of the climactic sequences deploys a red herring to show a fantasy-driven possible ending to the film—where Mampu exacts revenge on the political candidate by choking him with a film reel as her grandfather plays the sarod recital that had been cut short by his death in the car crash.

While there is a hint that this could be the audience’s fantasy, it could as well be read as a projection of Mampu’s own unrealised desire, rather than a larger position on the deflected debate. As with the issue of the city’s name change, Shoebox resists taking sides overtly. It creates ample room for the viewer to occupy different positions at different times, and watch it unfold through alternative lenses (even though the film’s colour palette is heavily tinged with a sense of nostalgia).

.jpg)

The magic of projection, almost like the aurora borealis glow.

This elegy to the single-screen theatre was a reminder for me that the moment of mourning is a short-lived one: one that perhaps only exists in and as art. After we have recognised the passing of something we hold dear, and before we—like rationalists and philistines—pose the unanswerable question: “In the greater scheme of things, so what?”—that moment can expand and talk of things that matter in the world, human and non-human. It is up to the artist to treat it with as much dignity and disinterested fairness as can be mustered. This is not an easy task.

Shoebox is screening online till the 14th of November (today) as part of the Dharamshala International Film Festival 2021.

All images from Shoebox by Faraz Ali. 2021. Images courtesy of the director.

To read about some of the other films playing at the festival, please click here, here, here and here.