Exhibitions as a Series of Statements: An Interview with David Bate

Concerning Photography: Photographic Networks in Britain (c. 1971 to the Present), a conference celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of The Photographers’ Gallery, attempts to explore the robust history of photography in the UK. Re-examining the 1970s as a pivotal moment within British photography, a parallel strand that emerges and demands special attention is the role of exhibitions. Over the first day of this conference, the trajectory of exhibition-making was echoed through various lenses.

The first panel titled “Institutions, Infrastructures,” looked at institutions, particularly independent galleries through a historic lens. Anne McNeill spoke about the Impressions Gallery, Bradford as one of the first photography galleries; Taous Dahmani shed light on the Autograph ABP as another such example focusing on Caribbean, African and Indian diasporas. Historian and educator David Bate presented a snapshot of the year 1979, as portrayed through the exhibition Three Perspectives on Photography: Recent British Photography, and Annebella Pollen presented on the international visibility of British photography facilitated by the British Council.

An overview of the state of photographic education and its beginnings was the focus of the second panel titled "Pedagogies." Exploring how exhibition histories get folded into the present, Juliet Hacking compared models of education across the US, UK and other parts of Europe; while Anne Lyden presented the case study of the Glasgow School of Art as one of the first programmes in photography. Andrew Dewdney explored the notion of the future of photography, taking into consideration the new condition of the image and how we may think of its admittance into the art museum. In conclusion, the keynote presentation by artist Mahtab Hussain evoked the lived experience of these histories and attempts to fold his own identity, heritage and displacement into the photographic histories that represent Britain.

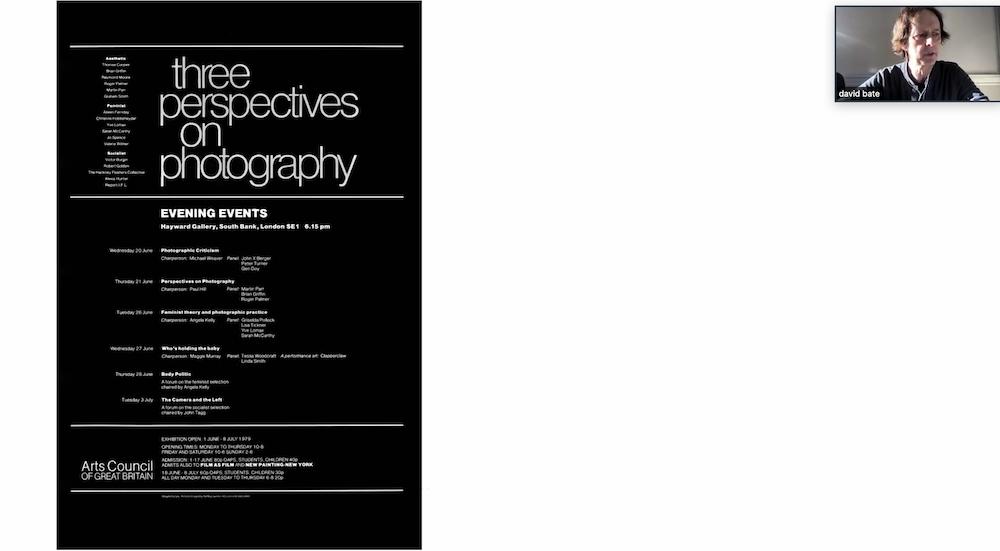

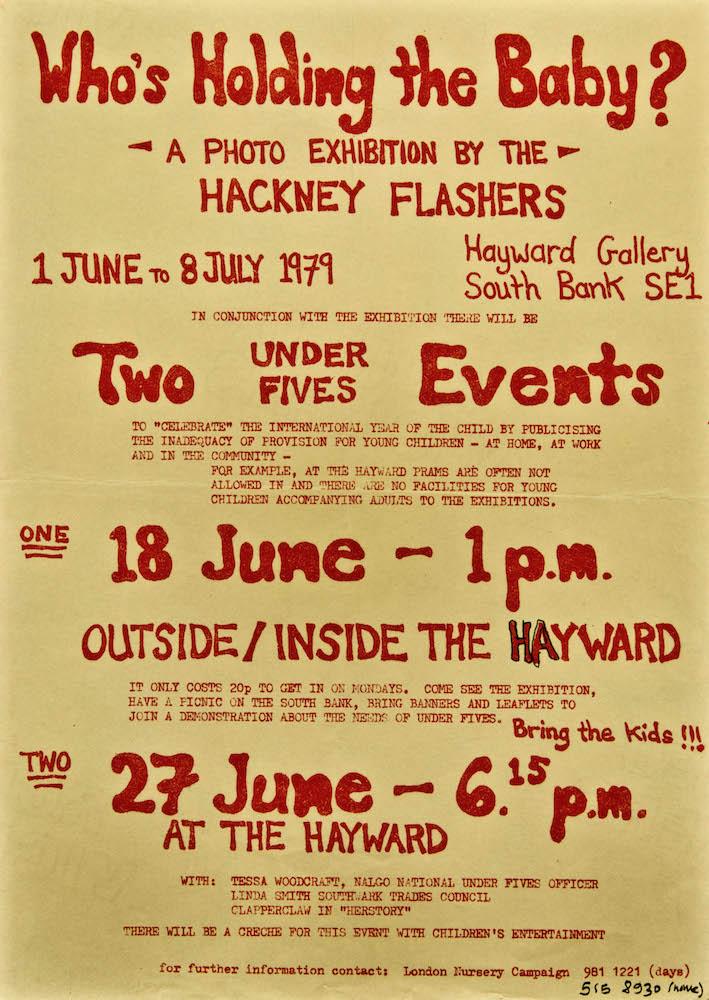

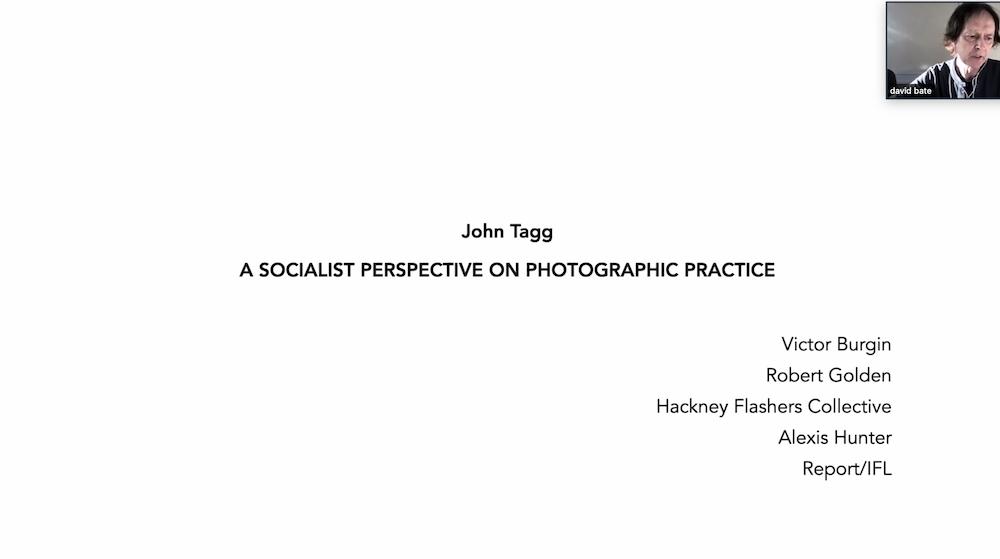

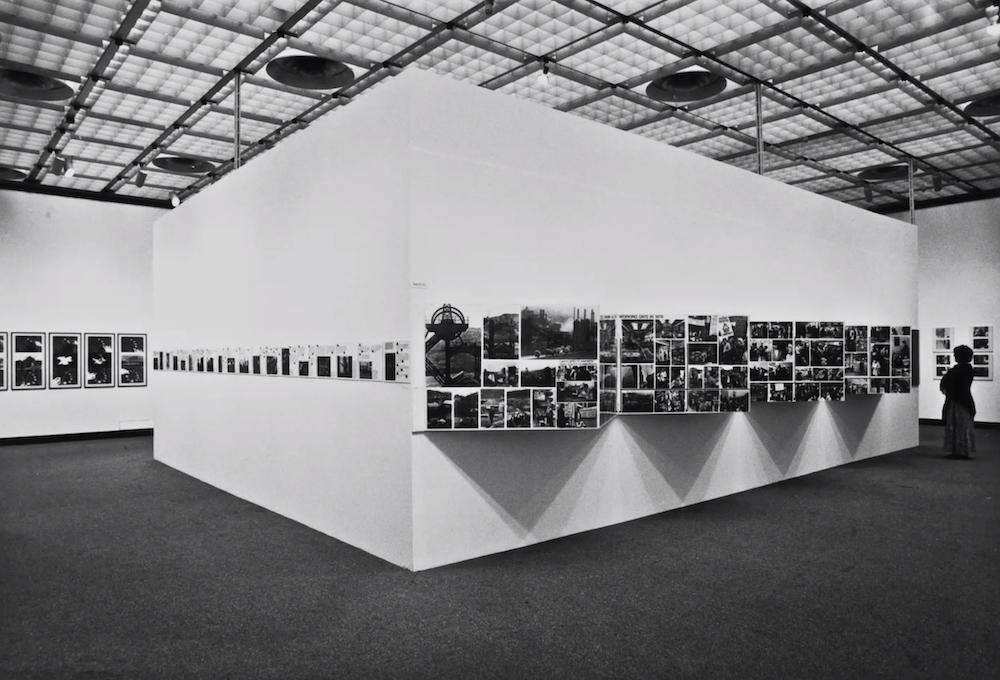

Held at the Hayward Gallery in 1979, Three Perspectives on Photography: Recent British Photography was the focus of David Bate's presentation titled "1979: A Snapshot of the UK." The exhibition consisted of three sections, namely: “Photographic Truth, Metaphor and Individual Expression,” “Feminism and Photography,” and “A Socialist Perspective on Photographic Practice” devised by curators Paul Hill, Angela Kelly and John Tagg, respectively. Despite being called the “…untidy title of an untidily conceived exhibition” by critic Stuart Morgan, it was one of the most widely attended exhibitions of its time. David Bate, in his presentation, highlighted the boldness of this “untidiness,” both in idea and execution, as a way to express the context of the time—a “statement” on the moment. Emphasising this particular curatorial strategy, the talk narrated and analysed the significant impact of the exhibition. In the following interview with Bate, we discuss the importance of the exhibition in fostering photographic interest, evolutions in its conception and the resultant changes in photographic pedagogy.

Sukanya Baskar (SB): While speaking about the 1970s, you made a comment about the relevance of “exhibitions as a series of statements.” I was wondering if you could expand a little on why the exhibition has held such importance within the field of photography and photographic history?

David Bate (DB): What I meant by “exhibitions as a series of statements” was that they can be seen as the “speech acts” of any given institution. So, for the purpose of historical analysis, this would include its curatorial statements, the space and its arrangement, organisation, etc. I draw here on the work of the French philosopher and historian Michel Foucault for a model of thinking about the past as a set of practices working in frameworks, that define those practices. To me, the emergence of photography galleries in the UK in the 1970s is symptomatic of a new plural, social demand—to see and be seen outside of the constrictive media and institutions that held sway at that time.

The importance of the exhibition, as a form, relates to two overlapping aspects. One is that independent photography (until the early 1980s) tended to be a craft tradition. Photographers made their own prints by hand for aesthetic reasons and to maintain control over their process. The print mattered as a “picture,” because photography required considerable technical skill and expertise. So, in an exhibition you can see the quality of the hand-made print, which looks different from a newspaper reproduction. And it was free of editorial control, except negotiating gallery curators, of course. The second reason is the social aspect of an exhibition—a gallery is a space where people can gather. So, it is no surprise that the informal conversations that happen in galleries between visitors, photographers and gallery staff eventually became formalised into “educational” events and workshops.

Photography exhibitions offered a social space, via the gallery, to those whose values were not included or allowed elsewhere, those who were not served by either the main art institutions or mass media industries. Perhaps this is why so many different marginalised social groups gravitated towards photography as a means of representation, aesthetic expression and identity. It was new, and offered a notion of poetic “truth” or creative communication.

Despite the growing demands and popularity of an alternative format, the photobook, photography specific exhibitions have continued to increase through newer networks of international festivals and photo fairs. These not only put on temporary exhibitions of wall-based work by individuals, but display photobooks too. The last time I was in China, I was amazed to see school children being taken to a photography festival to look at the exhibition of photobooks as an educational activity. I am sure I do not need to point out that all this demand for physical social interaction is parallel or perhaps even in response to the digitisation of social institutions.

SB: Taking the example of Three Perspectives on Photography, I gather from the brochure that public programmes were also held under the same thematics as the exhibition. Was this a novel approach at the time?

DB: My understanding of the events at the Three Perspectives on Photography show was that they aimed to “amplify” and expand on each “perspective." Much of it was what we would call in today’s language “socially engaged” photography. John Tagg had said that he wanted to show that “socialist” photography was not a single “style,” look or issue. The same can be said of the other sections, which showed a diversity of practices rather than being homogeneous. “Feminism and Photography,” for example, was proposed as a question rather than a style. In any case, each required its own discussion, because it would have been so new to the audience. The idea in Jo Spence’s work, for instance, that you could go back to “family photographs” to interrogate the identity of your “self” was deeply disturbing to both the traditional view of art and what “photography” an art gallery could or should be about. Today, no one would even blink at such a proposition.

After my talk, several people who had visited the exhibition in 1979 (apart for the curators of the show!) got in touch to say how fascinating it had been to see all these different, then “new” photographic practices within the same exhibition. The Hayward Gallery is a very particular space, with different sized rooms on different levels so it already had “natural” architectural divisions.

SB: Within the context of photographic education—where exhibition history is one of the ways that we approach the medium—what are some of the changes that you see?

DB: Photography students have certainly responded to the changing conditions of photography and its exhibitionary conventions. This can be seen every year, as the goal of many courses in photography in the UK is still the degree show exhibition. Until the internet, this was the dominant form of recognition of the fruition of a project; but now it is much more likely to be accompanied by a book or a selection of images on an Instagram feed, website, etc.

As a tutor, I am aware that students are comfortable with the hybridity of outputs, as “transversal” formats. At the University of Westminster, these issues are part of the practice and theory curriculum for photography. From my own recent experiences of exhibiting projects, for example (an online exhibition located in India in 2020, data files sent for printing and exhibition to Pingyao International Photography Festival, China in 2021), I am conscious of how different the whole practical process is now—from production issues to the dynamics of exhibition preparation. The pandemic has accelerated these changes too. Technically, digital printing offers much more diversity of output than analogue photography ever did. On the other hand, modern and contemporary art has also often privileged “outmoded” technologies, as Walter Benjamin had already noted in the 1930s. So, now we have to add certain forms of photography to that.

The notion of “expanded photography” which celebrates the photographic as object—whether as three-dimensional forms, performances, moving/static image objects, installations, or the so-called “post-photographic” fictive practices—is also symptomatic of these shifts. If the world of social communications works almost exclusively now on digitised screens, then the critical question for photography education and its research is to consider—what is the “object” of photography? These are the issues that face the old networks of galleries too, or at least pose useful questions to think about the future and present of photography.

Concerning Photography: The Photographers’ Gallery and Photographic Networks in Britain (c.1971 to the Present) is being held online from 25 November 2021 to 2 December 2021. Please click here to access the conference webpage.

To know more about the conference, please click here and here.

All images are screenshots from the presentation "1979: A Snapshot of the UK" by David Bate as part of Concerning Photography. 25 November 2021. Images courtesy of David Bate.