Material Media: Emergent Ontologies and Enquiries

The panel, “Material, Process,” organised as part of the conference, Concerning Photography: Photographic Networks in Britain (c. 1971 to the Present), brought together curators working with the material medium of photography and its various extra-territorial iterations within, on the margins of, and outside the context of the traditional photo-museum. The confrontations, enmeshment and collisions of photography with screen and network cultures have resulted in multiple, intersecting discourses within the institution. This has shifted the way we engage with revised editions of photography as both tool and medium. The anthropogenic thinking embedded in digital cultures of photography is taken up for perusal in its capacity to pervade, saturate as well as exasperate, as familiar coordinates are recalibrated in the recognition of shifting agencies through the decades.

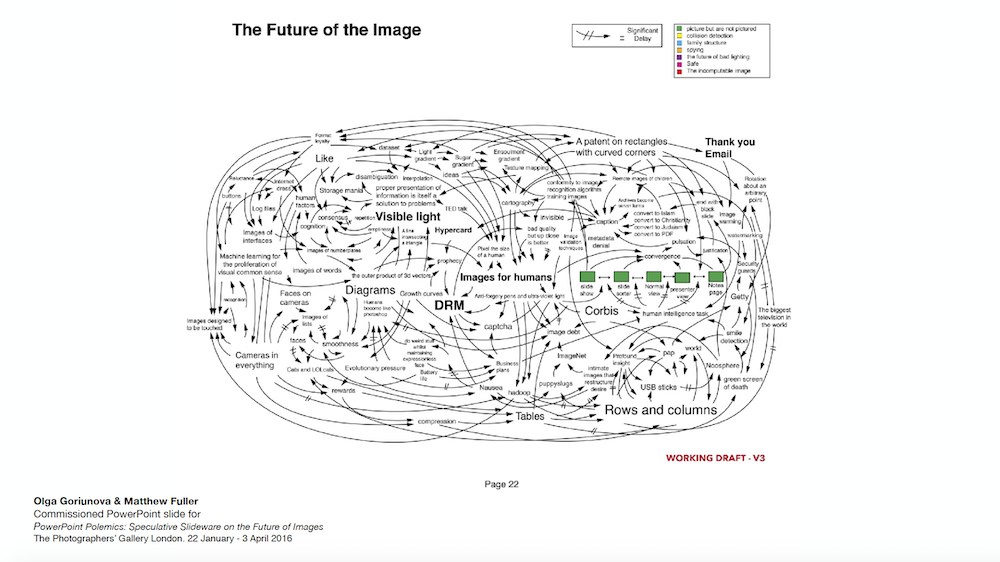

The Future of the Image, commissioned by The Photographers’ Gallery for PowerPoint Polemics: Speculative Slideware on the Future of Image. (Olga Goriunova and Matthew Fuller. 2016. Image courtesy of Katrina Sluis and the Photographers' Gallery.)

In their presentation, scholar Mo White elaborated on the use of slide-tapes by UK-based artists in the 1970s and 1980s, mostly as an interim form leading to engagement with more historically prominent time-based media such as film. The slide-tape consisted of a series of 35 mm positive slides that were projected, and often synchronised, with a tape soundtrack. Often, multiple projectors were involved, and the pulse command on the tape soundtrack allowed images to fade between them and to be synchronised with the sound. An analogue technology, it was mostly used for the purpose of educational instruction in schools and libraries. Owing to its low market price, the slide-tape became an accessible tool and affordable adjunct for many practitioners, especially Black artists, women artists and others practising on the margins of the mainstream gallery context. The slide-tape thus occupied a critical position in mediatic discourses, foregrounding minoritised voices (and narratives) in scaled frames of dispersion. White reminded us that there are no institutional archives or holdings for slide-tape works to date (at least in their original format), as the technology gradually fell into disuse (and invisibility) around the 1990s. An exception would be the Tate Modern, although it holds information exclusively on one critical body working with slide-tapes—the Black Audio Film Collective—owing to its critical mobilisation of archival imagery in the restructuring of colonial subjectivity. However, other works in the vein of formative experimentation are absent in public memory. A re-engagement with the form as “legacy media” by contemporary artists has meant locating the practice only within the framework of recollection. Claimed by no neat category, the slide-tape has thus elided an autonomous historical narrative, enabling instead a culture of consumption as a precursor to the moving image of the present age.

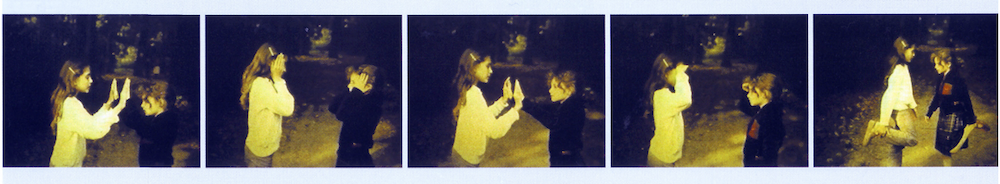

Clapping Songs. (Tina Keane. 1980. Slide-tape. Image courtesy of Mo White.)

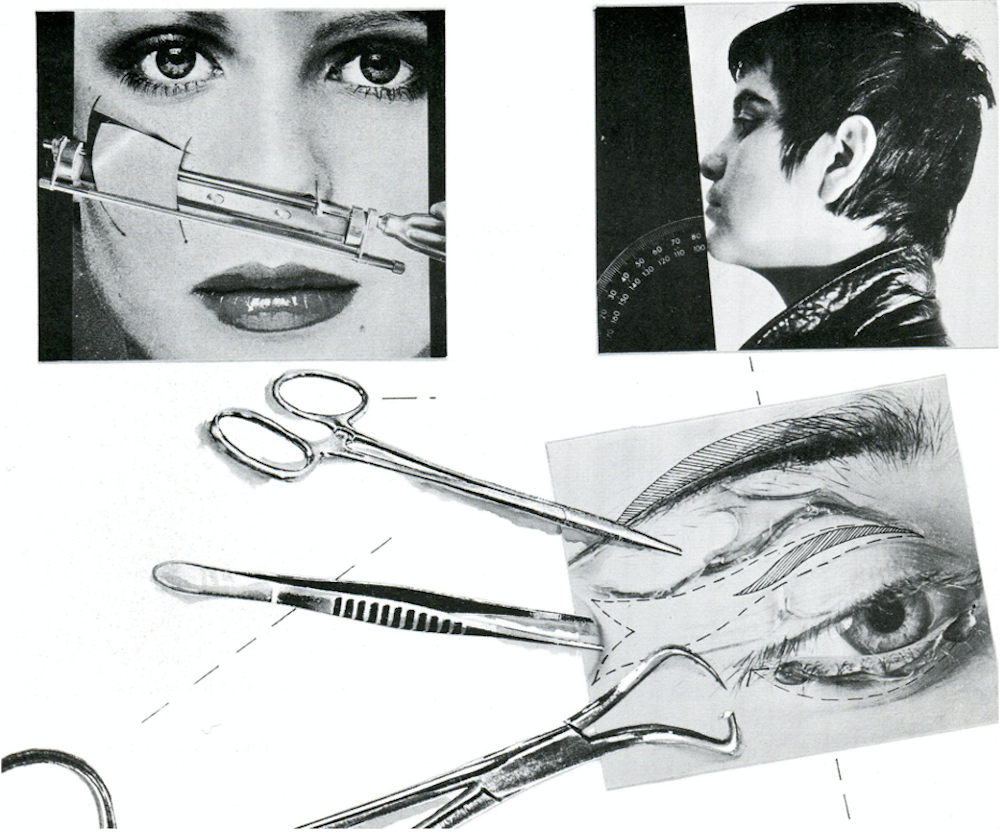

Short Cuts to Sharp Looks. (Roberta Graham. 1979. Slide-tape. Image courtesy of Mo White.)

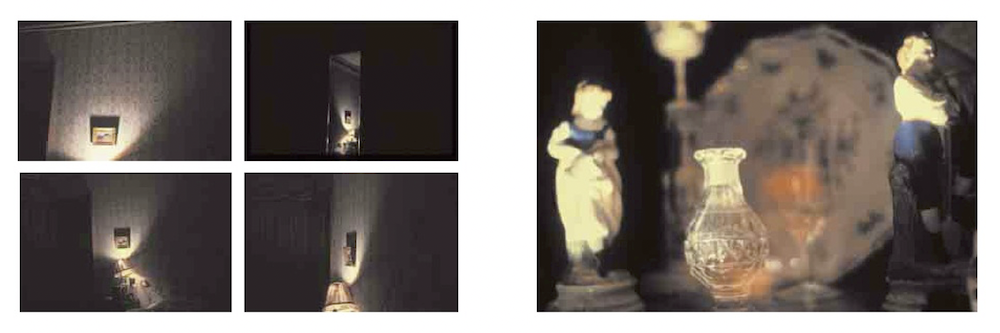

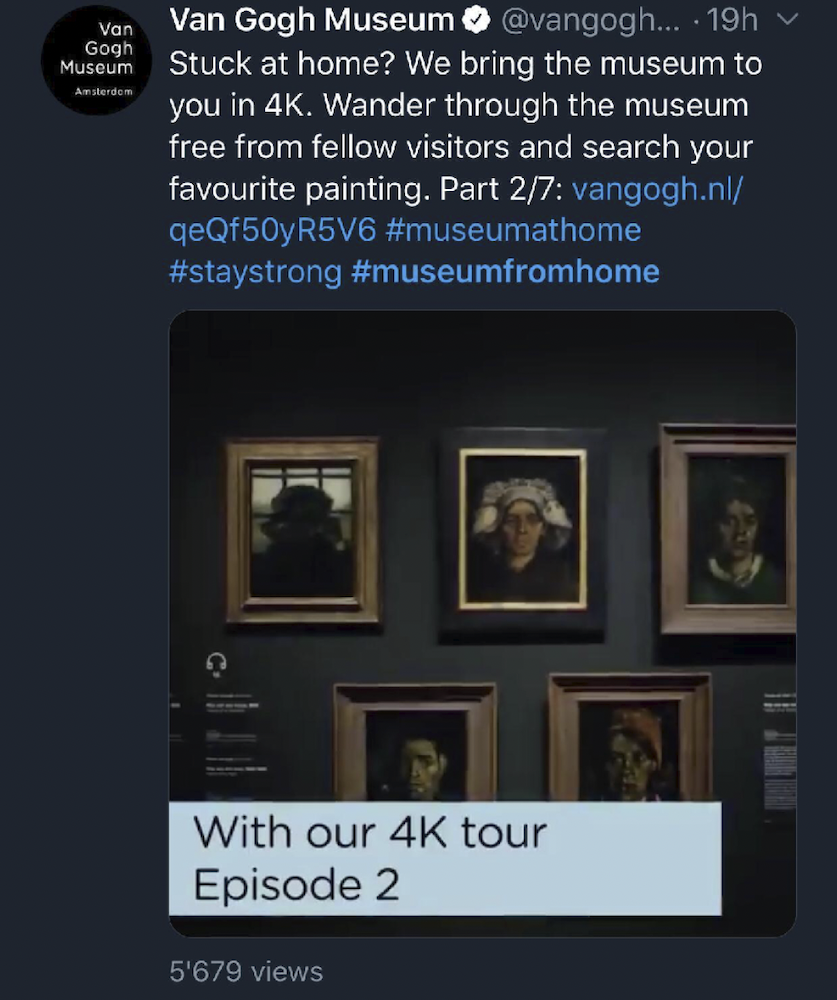

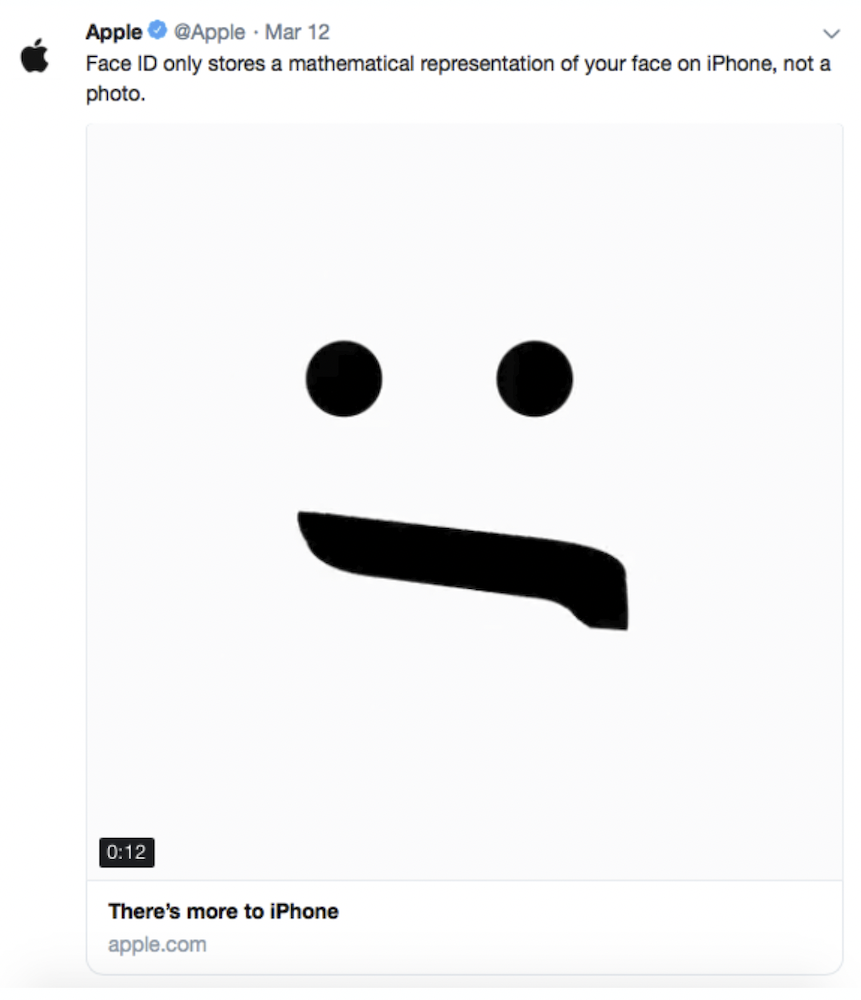

Older works involving the use of slide-tapes have often been re-staged in the contemporary moment—such as Nina Danino’s First Memory (1980, 2010)—which situates them in a moment where the gallery space was both threatened and enriched by post-photographic discourses around image-making. Having been appointed the inaugural Digital Curator at the Photographer’s Gallery—where she worked from 2011 to 2019—Katrina Sluis talked about the digital as a tool, medium of broadcast, as well as culture, in how it has been mobilised by artists to reformulate notions of photographic indexicality. Sluis was careful to problematise the analogue/digital binary by foregrounding their compatibility in areas such as digital post-production processes, where a manipulation of the pixel attested to the artist’s intervention—in the vein of the maker’s touch to their painting. The digital “turn” was then absorbed by museums under the guise of a new photographic avant-garde—when it did not pose a threat to the extant economies of the printed form, Sluis emphasised. But the digital photograph is “ubiquitous, immense, liquid,” pervading a space otherwise hallowed on the premises of preservation, exhibition and exclusion. The photographic image has been reconstituted as a “calculable surface,” explained Sluis, and has altered perceptions of the spaces that house them. For example, the 3K and 4K digital tours by museums (with increased resolutions, and by extension, viewing experiences akin to on-site flanerie) that intend a simulation of the analogue. The Covid-19 pandemic further encouraged the organisation of these tours, which, as Sluis pointed out, harvest valuable metadata that are otherwise generated by public engagements at the backend. Sluis’ appointment was a part of the institution’s attempt to navigate these changes, and one of the approaches proposed was collaborative practice-centred research. Sluis emphasised that such an approach would be suited to analyse image automation and the softwares enabling it by studying the vast infrastructure that constitutes the internet beyond anxieties around the crisis of authorship. Her first exhibition at the Gallery on its Media Wall, Born in 1987: The Animated GIF (2012-present), consisted of GIFs, a format “native” to the screen (as opposed to a digital iteration of the printed image). The exhibition encouraged a shift in understanding digital culture by moving beyond utopian visions of the internet as a democratising space by looking at the ethics of harvesting the labour of photographic communities to animate machinic vision. Navigating the cultural value of the image, the Media Wall became central to this research around new formats, economies of image-making and contemporary photographic datasets such as ImageNet.

First Memory. (Nina Danino. 1980. Multimedia installation. Image courtesy of Mo White.)

Sluis pointed out that the communities behind annotating images on the internet are an invisible labour force that is not adequately compensated for their work—a byproduct of the extractive rhetoric and practices of data capitalism. The question of labouring communities behind photographic processes was foregrounded through the case of the Grunwick strike, as Rowan Lear enumerated the historical event that helped improve working conditions in photofinishing factories. Having risen to prominence while meeting the market demand for improved photographic equipment in the 1970s, Grunwick hired the new immigrant communities in the UK. This primarily comprised South Asian women who had recently fled East African countries with their families following an imposed exile. Entitled to their circumstantial compulsions, Grunwick treated the workforce as cheap labour, subjecting them to racial discrimination. The photographic industry then promoted a new racialised hierarchy against the promise of emancipatory expression. The working force revolted against their anti-immigrant policies by mobilising colonial labour networks across the country and going on a long series of strikes in protest. At the time, Grunwick had opened a mail order service to receive and develop photographs. By refusing to keep the postal service running for the industry, the workers effectively put a halt to their labour through a kinship forged across communities. Lear kept the historical images from the strike deliberately blurred throughout her presentation, questioning the notion of representation in this context: who has the power to share and show? Undercutting the spectacle attendant to the images, Lear refrained from engaging in mediatic repetition, focusing instead on the latent energies that ran through the photographic subjects in cumulative view.

Tweet about a 4K tour at the Van Gogh Museum. (Image courtesy of Katrina Sluis.)

Tweet about Apple Face ID. (Image courtesy of Katrina Sluis.)

A similar case study of community-led initiatives was discussed by panelist Peter Ride through an elaboration of the ArtAIDS project. Set up as a platform for artists to include their work on the “web” (as it was understood around its conception as a homogenous and limitless space of inclusion and access) in the absence of content that addressed the issue of AIDS, it was intended to be an open-submission project that invited relevant artwork. The works on the platform borrowed from each other in vocabulary, aesthetic and impulse, resulting in ontological confusions around authorship. A radical idea then, the possibility of photo-sharing opened up avenues for appropriation as well as anonymity, resulting in an altered ecology of photographic practice—one that is received as commonplace today in its attendant complexities.

Shironeko: AKA ‘Basket Cat’. For the LOL of Cats: Felines, Photography and the Web at The Photographers’ Gallery. (London, 2013. Image courtesy of Katrina Sluis.)

The question of inclusion and exclusion in activist spaces leads one to think about the control exercised on ownership and distribution of resources. The leader of the factory union at Grunwick, Jayaben Desai, had, on her disappointment with the decision of the larger body of the Trade Union to end her hunger strike against Grunwick, remarked:

“Trade Union support is like honey on the elbow—you can smell it, you can feel it, but you cannot taste it.”

As Lear clearly enumerated, the deployment of a technology can impact the communities involved in facilitating its use. It produces degrees of inequities that may be felt and understood, but never tasted in full measure for redress owing to inevitable fissures within the communities. These alliances that coalesce around the image are complicated by the removal of the image itself in digital cultures, as tangibility is resisted in favour of an ephemeral, contextless presence. New ecosystems have thus had to emerge against the ever-shifting architectonics of the web. Sluis talked about how, while the web introduced a liberatory rhetoric in free circulation of the image, it was also accompanied by a complex mode of stealth and corporate extraction of data; the AI is then a “political constellation” of information that is both dormant and hypervisible in its functions. In light of these conversations, institutions have had to reassess their relationship to the public beyond the market-driven imperative of expanding audiences. The curation of such a spectatorship entails understanding the politics of expanded lens-based practices, their haptic possibilities, the experiential mappings they enable, as well as the possibility of a techno-material landscape of broken links borne from durational abundance. Traversing micro-sites of intimacy across a de-realised landscape, the migration of images to the online space has thus created a digital vernacular premised on new notions of the apparatus.

To learn more about the conference Concerning Photography organised by The Photographers' Gallery and the Paul Mellon Centre, please click here, here and here.