Linguistic Knots and Enduring Images: On Spandan Banerjee's English India

In colonial India, the English language was a central player in power relations between the British colonisers and the peoples of the colony, especially when it was introduced as a medium of instruction in the latter. Critic Samik Bandopadhyay argues that this was an insidious project—aimed at turning the new, aspiring Indian middle-class intelligentsia into perfect compradors and colonial agents of British power in India. In a continuation of this assimilative impulse in the contemporary moment, the degree of one’s “fluency” in the language determines such attributes as class and a potential professional standing. Spandan Banerjee’s English India (2015) begins with the nuances of the eponymous language as they are passed through generations in the Anglophone academia in Calcutta, a remnant of said instruction in the former imperial capital. The film takes this strain and segues into the occupational idiosyncrasies of tour guides in Delhi, who mobilise the language to guide English-speaking tourists and earn revenue from the work. In a pan-Indian economy that favours the use of English in the absence of a common counterpart in the vernacular, the language is also mostly acquired or learnt out of necessity—such as in the case of the guide. Banerjee represents this entanglement of need and aspiration through the guides’ trajectories around cultural landmarks in Delhi, as they attempt to straddle the roles of both escort and storyteller. Using a cinematic lens to peruse their many phrases, linguistic errors and the syntactical amalgam with native tongues, the film looks at the visual fantasia of a nation borne out of multilingual intimacies.

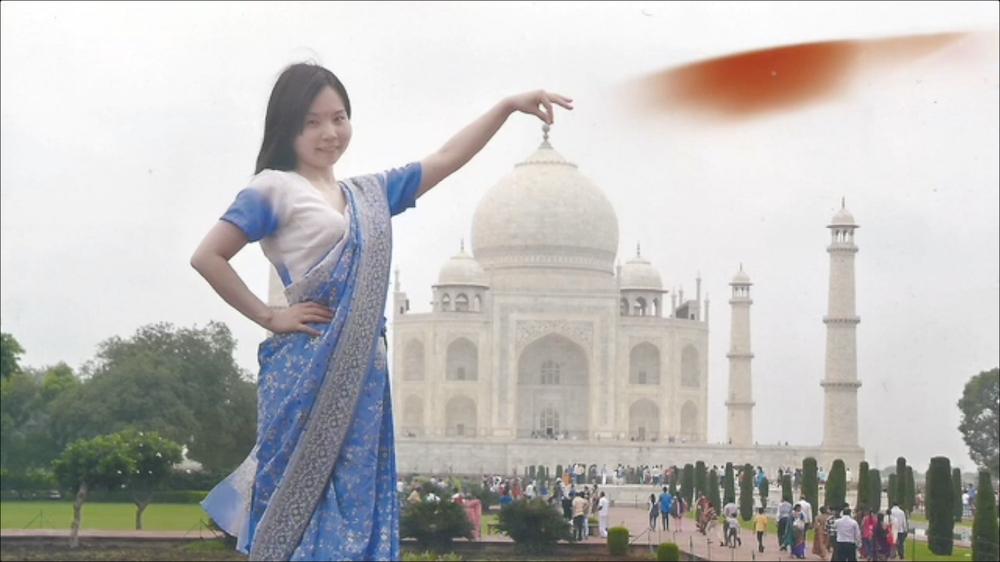

Using Anglicised vocal inflections and staple phrases of greeting and assurance (“No Problem” being a recurring example), the guides provide just enough information to satiate the average tourist, delving deeper into the concerned history only when probed further. As one of the tourist-respondents points out in the film, the tailoring of information—to the different levels of curiosity they may be confronted with—is an important skill carried by the tour guide. It precludes saturation with data while ensuring a token experience for the visitor. The Taj Mahal becomes an important visual motif in this transcultural exchange. Perennially busy, the premises of the monument are teeming with eager guides and photographers offering their services with ready specimens on site. A montage of these images punctuates the film, showing visitors posing around and with the Mahal in various permutations. We see them participate in illusions of holding the tip of the monument with their fingers, romantic demeanours in tandem with cinematic parlance around Mughal romance, and frozen mid-air while jumping—all while a formal placard nearby reads, “No Photography Allowed.” The monument’s symbolic import extends beyond its perimeters and percolates into the public consciousness through oral histories, songs and popular media, all of which render it impervious to official rules of constraint. The visitors engage in active memory-making through the aid of photography every day, creating an enduring syntax through time.

The film also takes the viewer through the bylanes of Delhi; rickshaw-pullers double as guides and lead visitors to off-beat attractions such as kabootarbaazi (pigeon-rearing)—a phenomenon that has continued from the hobbies of erstwhile Nawabs, and is distinct to Old Delhi cultures of leisure. This points to a nostalgia for a regal past, that is now marketed for tourist consumption through practical re-enactments. It is a yearning that ties up with the aspirational drive towards English and its correlation with a purported colonial grandeur, which, in turn, shapes the images as they are concocted by the guides with words, turns of phrases and in calculation of the tourists’ expectations. However, the viewer is soon informed about the increasingly rapid substitution of personal guides with audio applications on historical sites, which create a manicured (and homogenous) version of the viewing experience. In the absence of the guides in person, the applications erase the sounds, jokes and moments of shifting ease that were attendant to interpersonal exchanges. As the surviving guides try to make a living, the English language is spoken across these public spaces through a recursive subroutine, effectively rewriting its cultural import in the indigenous context. Existing in a continuum governed by the contingencies of reception, the language among said working class is mostly learnt outside the institution—through aural absorption and oral practice—in departure from its first motivations during the colonial period. From a language proper, it mutates through use into a freely accessible text, open to appropriation; there is no “correct” way to speak this English.

All images from English India by Spandan Banerjee. 2015. Images courtesy of the director.