Fluvial Embodiments: On Abhinava Bhattacharyya’s Jamnapaar

“Jamnapaar” translates to “trans-Yamuna,” and refers to the eponymous river in a state of passage—running through Delhi, dividing the city into two relatively favourable halves. Populated mostly by migrant communities from neighbouring states, the suburbs on the banks are often viewed pejoratively—as a land on the underside of mainland Delhi. The eastern bank especially—which was not under the purview of imperial Delhi or its former counterparts—began to be inhabited by refugees following the Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, and later, the Emergency in the 1970s. During the latter event, the basin became a site for resettlement colonies for the impoverished and disenfranchised, resulting in a precarious life by the river, attendant with informal economies of livelihood. Having previously worked on the riverine hydrology and intimate publics of Delhi, filmmaker Abhinava Bhattacharyya found himself drawn to the Yamuna River and life around the Delhi Ridge (or the Aravalli Range) in preparation for his diploma film, titled Jamnapaar (2017), as part of the Creative Documentary Course at Sri Aurobindo Centre for Arts and Communication (SACAC), New Delhi. He points out how, while growing up in the metropolitan city, the river was always relegated to the periphery of ocular cultures, which rendered it a “sensory assault” on his first view of the waters in person. Replete with sewage, plastic and a plethora of waste on and below the surface, the river carries the weight of an Otherness that makes visible the city’s many inequalities of resource consumption.

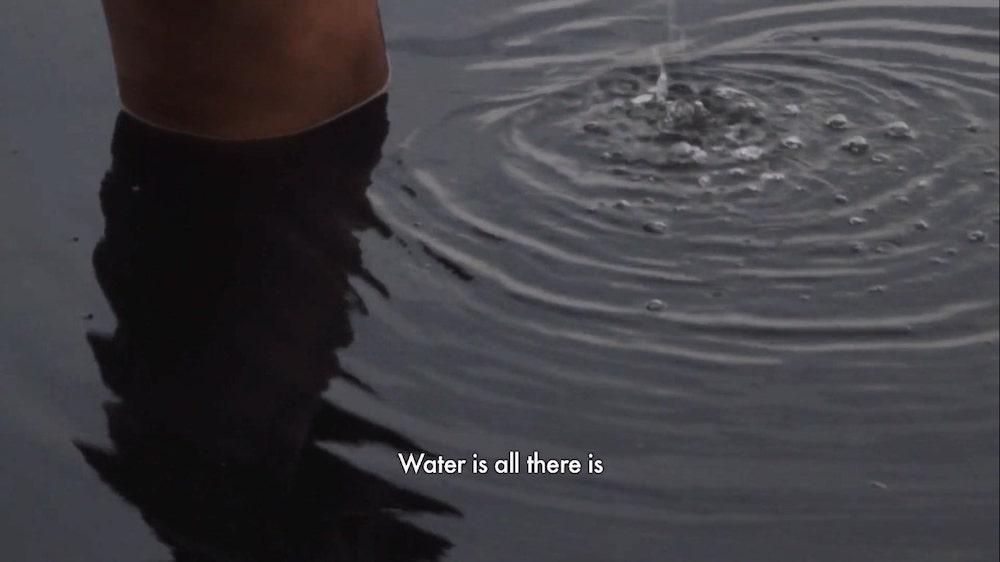

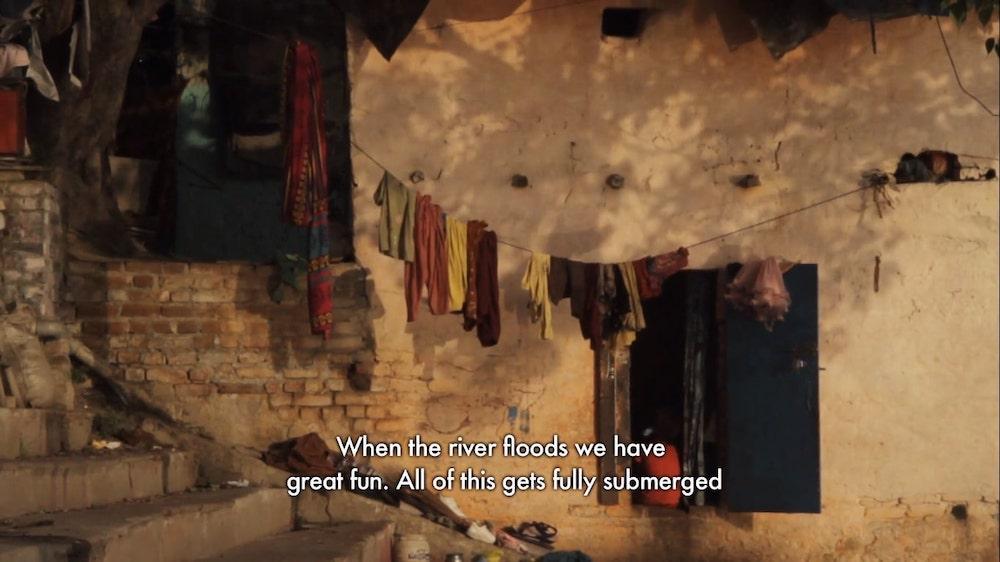

The narrative anchor of the film—having emerged as one on the editing table, out of organic connections between vignettes—is an aged man who works as a tea-stall owner for half the year, and as diver/lifeguard for the other half. Talking about the technicalities of saving drowning bodies and the eerie regularity of its occurrence, he emphasises how the river is the mainstay of the inhabiting communities. Worshipped as a sacred river, there are historical accounts of the Yamuna as a body of pristine waters that date as far back as the thirteenth-century; but no living body seems to remember it except in its present state of dilapidation—explains Bhattacharyya. An imagination informed by its contradictory state in the contemporary, the river acquires the tone of a personal mythology as the protagonist laments its purported loss of piety. Children talk about having caught a three-headed snake during floods that otherwise submerged their houses—attesting to the emergence of many publics through intimate scripts around the water. Acting as a reflective screen to the life unfolding around it, the water absorbs the colourful hues of the sky, which are exaggerated in the cinematic syntax as a contrasting palette to the river’s general pallor. Birds also become an important motif in that Bhattacharyya captures Siberian gulls migrating to the toxic river in their annual flight—in a strange magnetic pull towards a perishing body. Is it only because the route is embedded in their memory-system from evolutionary patterns of avian navigation? What could the past of the river have looked like? Through subtle flights of fantasy, the filmmaker wonders along with the protagonist.

“How do you represent a degraded site?”—this was the pivotal question posed by mentors Sameera Jain and Ruchika Negi that encouraged Bhattacharyya to find a language through which to shape his optics around the subject of the film. A repository of the city’s garbage, chemicals and other excrement, the Yamuna River is part of the planetary archive of meaning and matter. Percolating into and diminishing marine life, the waste has altered the ecology of the river, while human life has sprung and persisted in a precarious entanglement with its toxic constituents. Refusing assimilation into its environment, the pervasive presence of plastic on the water points to its recalcitrance, sealing off the cyclical mechanisms of circulating matter. Interspersed with discarded flora and foliage, the plastic waste creates a hybrid sensorial regime for life on the margins, as a rag-picker is seen collecting potentially usable polythene from the waters with an oar. Entering geological time, the toxins in the waters permeate the human bodies living in and around the river—resulting in an attritional violence cohabiting with plural fictions. At one point, the diver remarks that an image captured on a reel is permanent unlike memory, which is personal and subject to illegibility. Through this film, Bhattacharyya confronts the failure to imagine an idyllic past for the river by looking for a new language of being through his camera—one where the river and its peoples exist in shifting relations of aqueous corporeality.

All images from Jamnapaar by Abhinava Bhattacharyya. Delhi, 2017. Images courtesy of the director and Sri Aurobindo Centre for Arts and Communication.