Nationhood, Interrupted: On Moonis Ahmad Shah’s Material for a Love Letter to Comrades from the Subcontinent

Across a diptych-like frame, artist Moonis Ahmad Shah places disparate elements in dialogue with one another to foreground the absurdity embedded in the arrangement of landscapes per territorial politics. As a construct, borders are contentious, and charged with complex claims to ownership. Borders enable a taxonomic dissection of land, demarcating its constituent inhabitants into separate systems of institutional care. In the video, Material for a Love Letter to Comrades from the Subcontinent (2021), the simultaneous absurdity and ubiquity of marked land is evoked in how it also shapes or resists dominant ideologies, perpetrated by normative voices. Working with digital and forensic vocabularies, Shah’s concerns revolve around the Othered body, and how narratives may be reconstructed through archival re-imaginations. Screened at the VAICA Festival 2021 under the thematic capsule, “Urban Heterotopias,” this multimedia video gestures towards the fissures in popular understandings of nationhood, and how ground realities are often at a vast remove from the celebratory patriotism that is cultivated through repetitive utterances and affirmation.

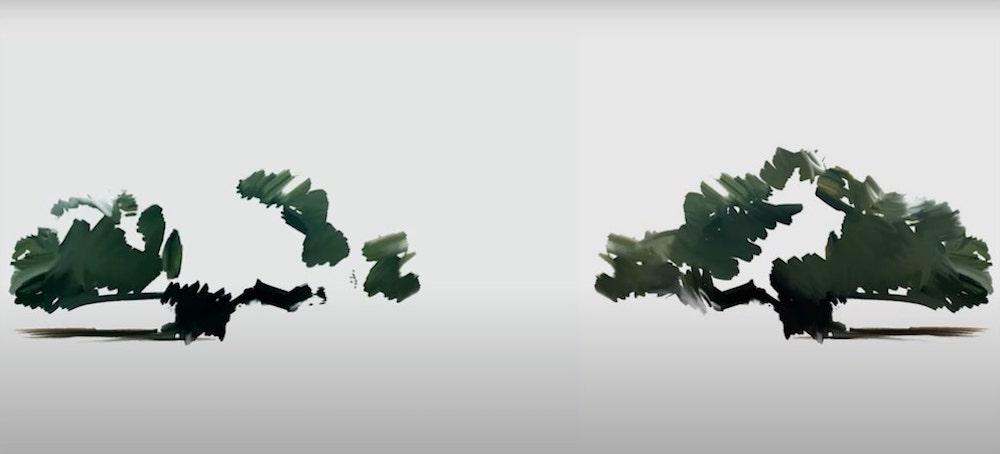

The diegetic composition comprises an expansive garbage dump; on either side of the median, a white screen is mounted without context. In tandem with a children’s chorus in the backdrop, the screens chart digital representations of trees and clouds, as the terms of their origin are debated in sing-song queries. The mirrored wastelands are sutured by their subsumption into a “national” imagination that is increasingly challenged today by the pulsating reality of state-inflicted violence, border skirmishes, pellet injuries, mass disappearances and psychological afflictions―all of which are narratives omitted from official accounts of governance. The normative tableau of said imagination―in its ceremonial flag-hoisting performance of passion―evokes a participating populace that is seemingly settled, felicitous and accepting of the idea of the “nation” as determined by its patriotic (and patriarchal) agents of power. The wasteland in the video actively runs contrary to this inclination, as it portrays a land choking on pollutants, which will possibly stream into the water bodies nearby, and alter the ecosystem in accumulative strides. The optical reproduction of the tree on the screen becomes prescient in this light, as it evokes an arboreal transfer to the virtual; the land is teeming with irresolvable debris.

The children’s chorus―which increases in density and intensity during the run of the video―carries an innocence that is also indoctrinated. “Woh ek Pakistani baadal hai” (“That is a Pakistani cloud”) especially encapsulates the absurdity of assigning nationhood to such an entity as vapour, and consequently points to water’s porous ontology and permeable trajectory over lands. The purported legitimacy of the border persists through a transfer of such pronouncements until they assume veracity. As one child voices it, and others repeat, the chorus acquires the tone of instruction that gradually transforms into an illegible cacophony. It may be surmised how children become carriers of vested ideologies at a formative age. The absent bodies of the singing children in the video further points to their actual erasure from cartographic imaginations of conflict areas, such as Kashmir. The garbage dump seems to assume the silhouette of a shrine, which imbues it with a quality of piety. The chorus, in this light, starts to sound like sermons broadcast on speakers from a house of worship. The dissonance of this imagination with its referential counterpart suggests a neocolonial imagination of nationhood, informed by a perpetual undercurrent of terror and the threat of dissolution. Minority communities are hypervisible in such visions of the future in the anticipation of their absence or assimilation, which alters as well as normalises a version of nationalism premised on subtraction. Borders are sustained through strategic storytelling―a tool re-imagined by the artist here through a recalibration of ecological distress as an effect of (and mirror to) prolonged trauma.

To read more about Moonis Ahmad Shah, please click here and here.

To read more about the works featured as part of VAICA's festival Fields of Vision, please click here, here, here and here.

All images from Material for a Love Letter to Comrades from the Subcontinent by Moonis Ahmad Shah. 2021. Images courtesy of the artist and VAICA.