Conflict Sites and Militant Botany: Moonis Ahmad Shah’s Gul-e-Curfew

Corpse Leuk has no scientific name as it defies the current taxonomy and its systems of organisation. They grow on the walls of prisons as well as torture and detention centres. They emerge from either beneath the executioner’s or the jailer’s chair, or behind it; their growth resting on every human wail heard. They undergo radical fission that causes the structure in which they have laid their roots to fall down to rubble.

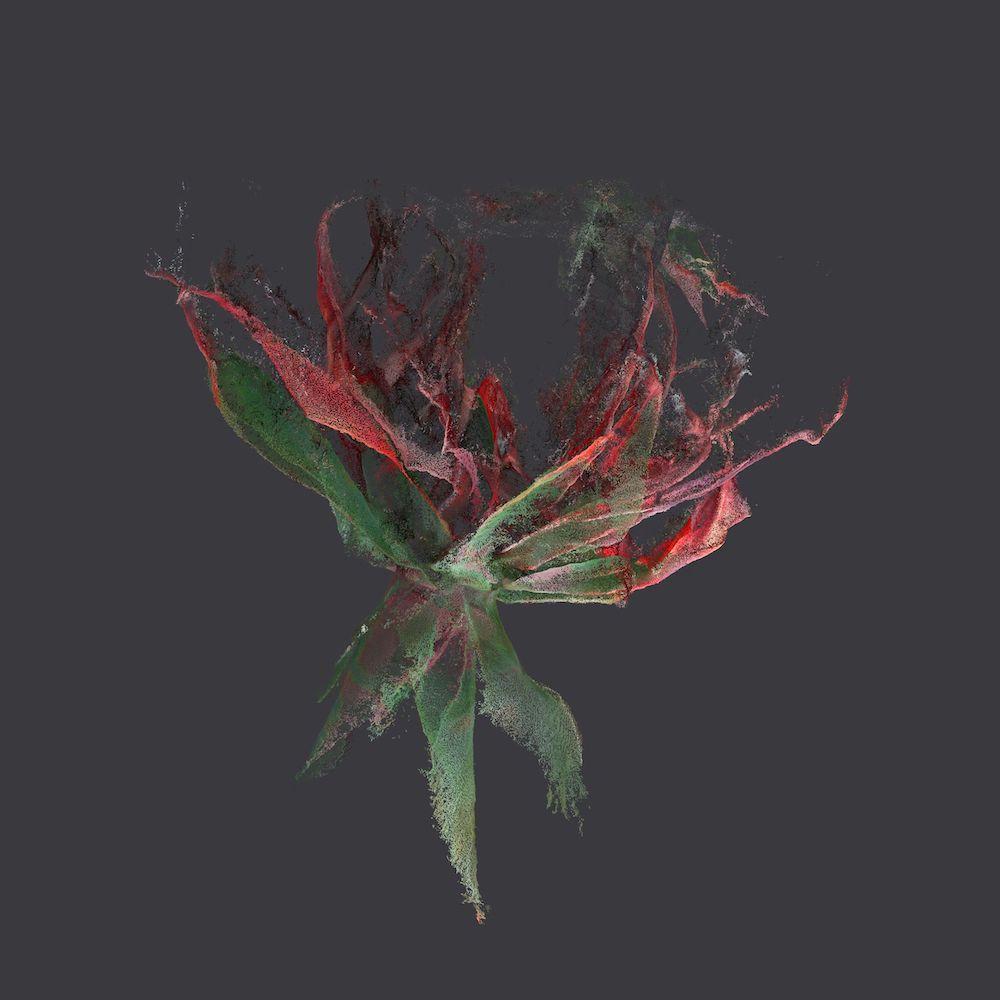

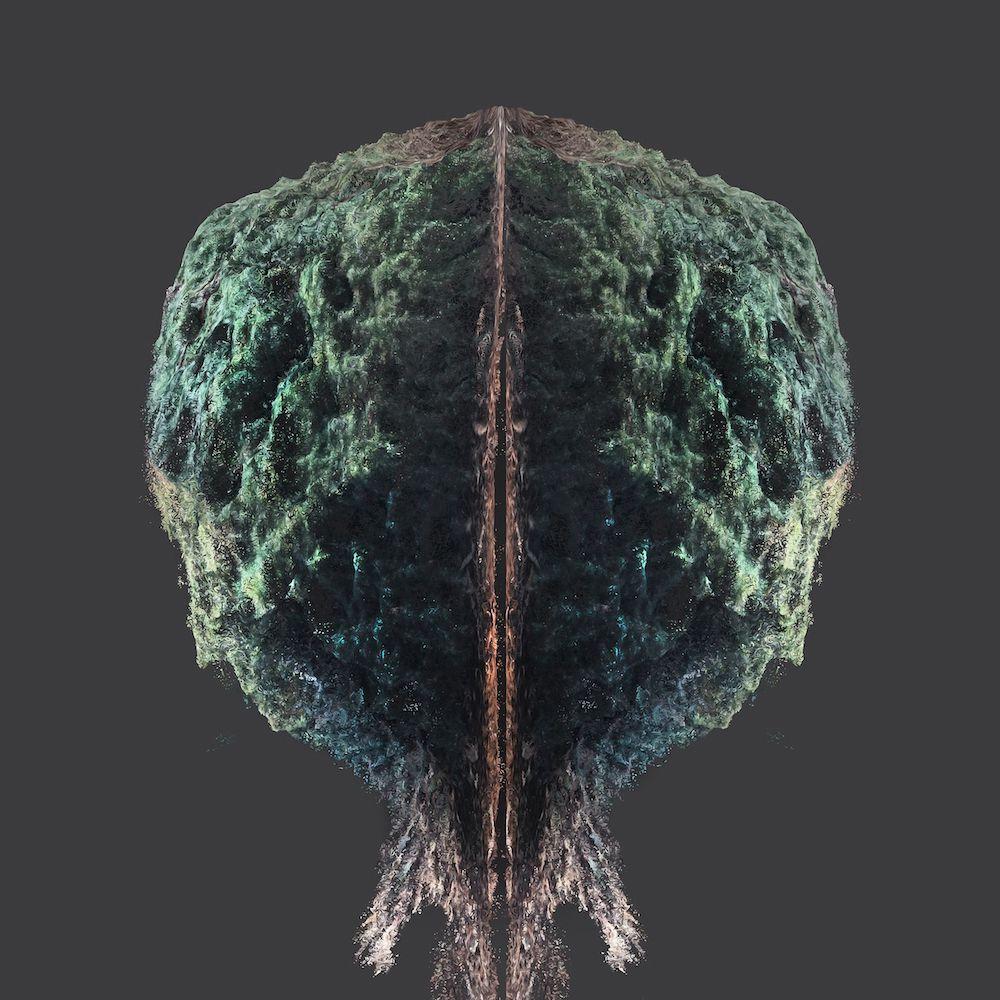

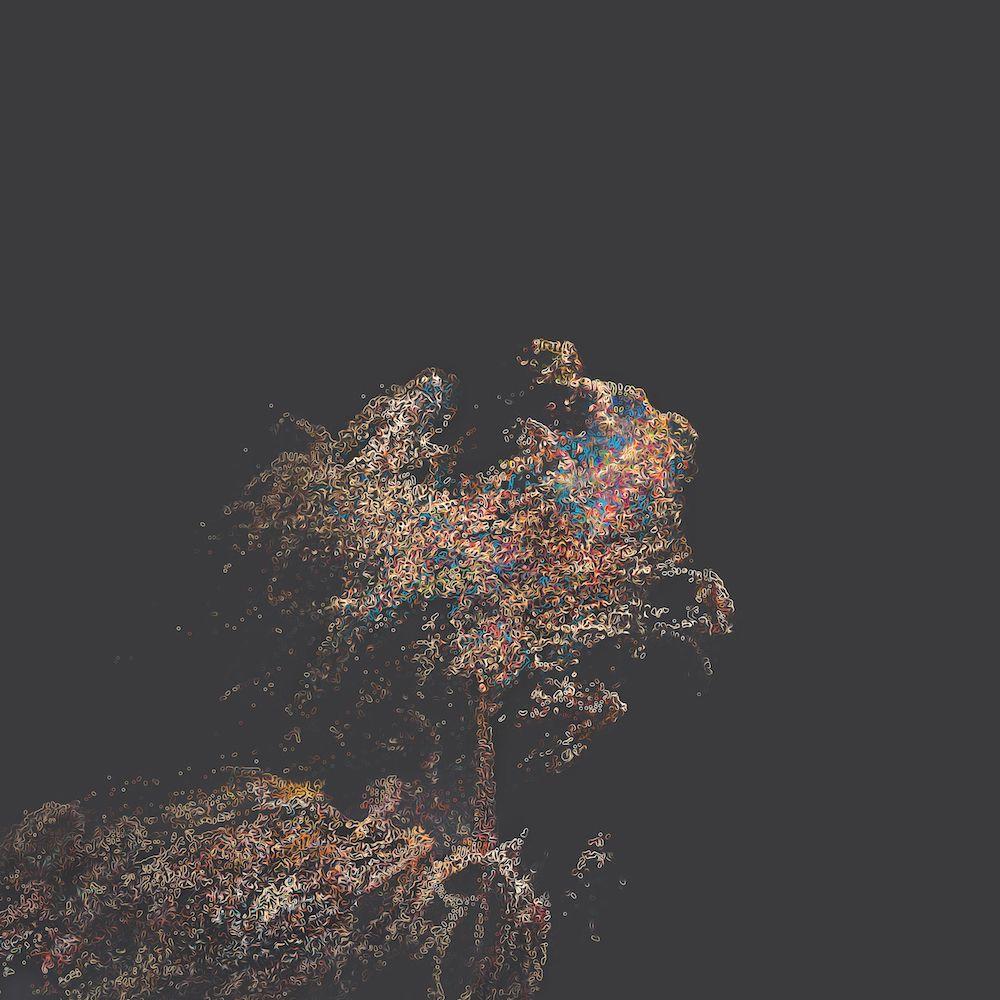

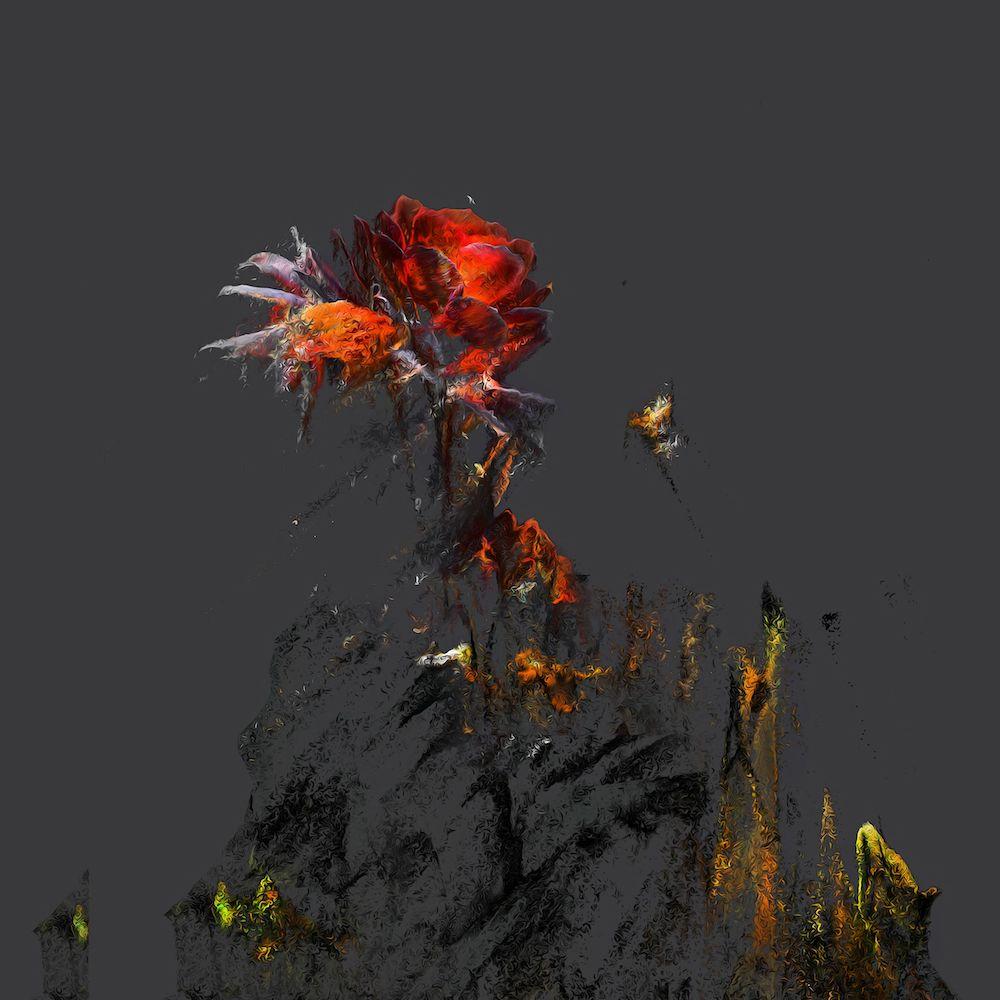

What happens when a conflict persists for decades on a territory? Does it lead to evolutionary adaptations from obligations of anchorage? How do the air, water, flora and fauna navigate a site of distress alongside human fatigue and anxieties around extinction? Moonis Ahmad Shah charts a taxonomic model for botanical forms that have seemingly evolved in tandem with the constraints, dilations and extractions prevalent in contested zones. These representations of flora are accompanied by notes on their anatomy, lifespan, sites of discovery and causes of disintegration in response to the specific nature of the conflicts that engulf them. Their emergence, “growth” and “de-growth” are enabled and sustained by the terror of perpetual threat to existence as well as the possibilities of resistance through laughter, rest and seepage. For Shah, this “anarchic archive” of militant organisms is both process and strategy, directed at destabilising colonial taxonomies and histories of the present.

Ubax Baroor Diq Ah flowers in unknown micro-frequencies from a rhythm or anything that resembles music, and its process of decay begins when it hears mourning music. It grows into a black hole that swallows everything that comes in its way, even with the slightest touch. It can also curate doorways to unknown languages that articulate the otherwise incomprehensible, and can only be seen or felt by poets who dry their blood in snow.

Yanlei Uighur’s growth and decay have a strange symbiotic relationship, and it begins when the proportion of salt in a mixture of tears to blood is six to five. The light it emits leads to euphoric possibilities such as friendship, love, touch, militancy and music in places where they are systematically made impossible. They emerge in concentration camps and subvert the memory of the powerful, turning them into tiny dots of infinite laughter.

Titled Gul-e-Curfew: An Index of the Strange and Inconsistent Phantoms from Everywhere, the series (and publication) constitutes images that are based on actual botanical forms―they were photographed in 360-degree motion before being digitally rendered into point clouds from the accumulated data. The point clouds were further processed until the resultant images emerged, creating hybrid bodies that confuse the lines between fact and fiction. The original botanical form thus evolves beyond its initial point of reference in the process, creating an altered biological configuration. Each one of its names is constructed from the vernacular language spoken in its purported area of origin―whether Pulwama or Gaza―from which the particular form has been sourced. Cumulatively, the images create an alternative epistemology of subterranean militancy with a genesis in the algorithm. This permeates a military landscape through new articulations, challenging the fascist vision of power as discrete and atomised. Through shared cognition of the conflict, the sentient forms establish aqueous connections across land, water and concrete, creating new planetary archives of meaning and matter.

Byol-e-Siyah’s degeneration has been witnessed in places where words and silences were strangulated to form huge structures with beautiful idols. Its points of emergence are usually around press firms or newspaper agencies. It bursts into a zillion pieces, which turn into minute seeds like pollen―they enter the printing machines and the pens of scholars and dry their ink completely. They are also found to proliferate underneath the keys of laptops, desktops and other gadgets to create seepages and faults in the data archives of news agencies, especially those concerning contested territories.

Bulaklak Ideolohiya grows around water cannons getting ready to be sprayed at shouting protesters, large gatherings dispersed by pellets and other forms of ammunition, as well as dissent that progresses into a severe sense of rage and public vandalism. They turn into stray bullets when they sense a deep ideological emergence or rift. The bullets do not pierce, but turn to ash on contact with the human surface. The touch of this ash causes a severe case of schizophrenia, wherein the person begins to start seeing Karl Marx.

One of the loci in the project is Kashmir, which has been under siege long enough for the horrors of its lived reality to enter generational memory. Living on occupied land and subjecting its people to forced disappearances, death and pellet injuries that render body parts functionally invalid, the military infrastructure in Kashmir (backed by capital) has sought to make its mark on the territory through a lineage of invasive violence. Fences, walls, barbed wire and the debris of demolished habitats populate the landscape and compress its map, their resources consumed for the sustenance of the surveilling bodies. The recent attacks on Palestine by the settler-colonial state of Israel as well as the discreet, ongoing forced conversions of Uighur Muslims in China bespeak a similar drive towards ethnic cleansing of the historically marginalised. In such a global atmosphere of political antagonism, Shah imagines a host of trans-species that affect the architectonics of repressive pockets through morphological mutations. The organism eludes concerns around borders and proprietorship, dismantling rigid arrangements of ecologies as mandated by regimes of power. It has a fungal quality in the way it occupies spaces and emerges/dissipates in voluntary motions, reorganising the index into new frameworks of being with.

Zahrat al Aizdira viciously grows in silence, its morphological integration bound by the same unseen radiations that are nursed in the heart of nuclear fission. They grow around psychiatric hospitals, psychological clinics and beneath large volumes of psychoanalytic work on trauma in contested sites. Their presence radiates a strange heat that increases the temperature of the room, whose inhabitants thus experience a biblical euphoria as well as a sense of defeat when they cannot see the God of whom Moses sings.

Bir Banta Ko Lagid proliferates in silence underneath the clothes of strip-searched people and its most common form witnessed resembles a shroud. Hyper-sensitive to the presence of incarcerated people, it is believed to transform the fabric into the same metal out of which Don Quixote’s armour was made. It engulfs the fibre and cements itself like a rock, thus making the clothes impossible to remove, tear or burn.

To read more about Kashmir, please click here, here, here and here.

To read more about Palestine, please click here, here, here and here.

To read more about Shah's practice, please click here.

All images from Gul-e-Curfew: An Index of the Strange and Inconsistent Phantoms from Everywhere by Moonis Ahmad Shah. 2021. Captions extracted from the eponymous publication text written by Shah in collaboration with Hafsa Sayeed.