Images, Dreams and Other Porosities: On Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s SleepCinemaHotel

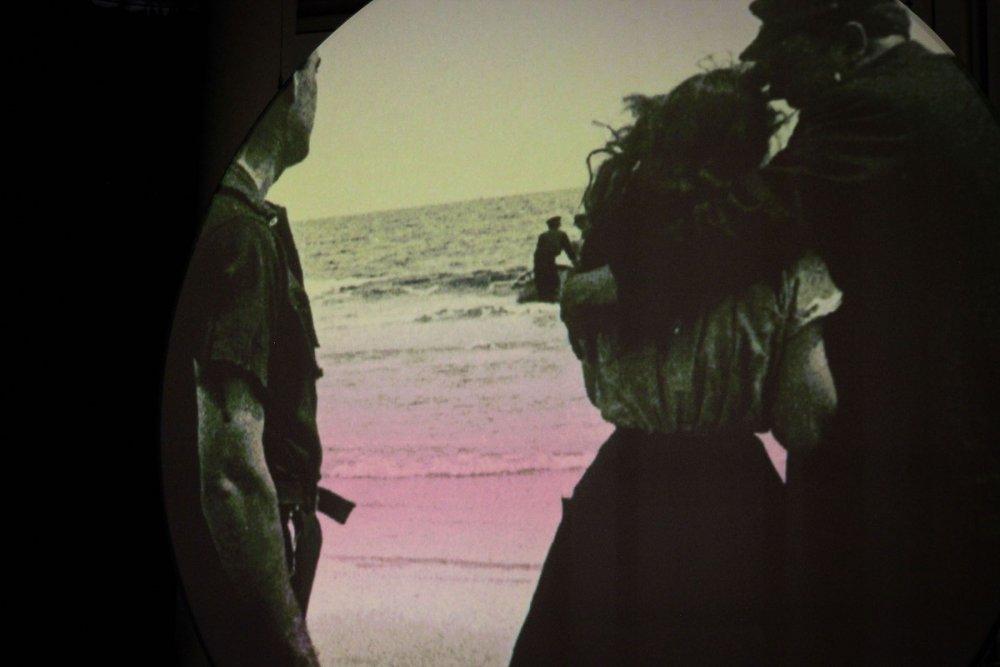

Detail, SleepCinemaHotel, 2018. (Image courtesy of Matt Turner, first published in Sight & Sound magazine.)

At the International Film Festival Rotterdam in 2018, the SleepCinemaHotel was set up as a fully functional space (albeit temporarily)—complete with showers, breakfast, amenities and an interlocking metal scaffolding of beds in the main space for the audience members. Designed as a communal dormitory space, the beds (at varying heights) faced a giant circular screen on which films and footage of animals, humans, clouds, waves and natural scenery were projected in an unlooped sequence over 120 hours. In the Hotel, Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul set up a condition for falling asleep to images—an act he encourages and has engaged in himself on the premise that dreaming (attendant to screen-slumber) is a form of personal cinema. He sourced the films from the EYE Filmmuseum and the Netherlands Institute of Sound and Vision, mobilising their archival material to create a liminal space of interaction where the past, the present and the spectral collide in a state of purported rest.

Detail, SleepCinemaHotel, 2018. (Image courtesy of Matt Turner, first published in Sight & Sound magazine.)

Detail, SleepCinemaHotel, 2018. (Image courtesy of Matt Turner, first published in Sight & Sound magazine.)

Rhythmically consonant with low-frequency sounds of the elements, the images in the Hotel play with the viewer’s subconsciousness, enabling an osmosis between states. Weerasethakul has spoken about how there are different cycles of sleep which cumulatively last ninety minutes—the average span of a feature film. Entering the dark space of the cinema then becomes an act of submitting to the biological need to dream for that length of time. He precludes the need for interpretation, suggesting that the flitting images instead create an expanded cinema through the senses in the act of collective dreaming. This intent can be traced in his feature films as well, especially Cemetery of Splendour (2015), where the narrative revolves around dreaming bodies in a perpetually immobile state. In the film, sleep is treated as a defence against an authoritarian regime, and a means of projecting the self beyond its immediate psycho-physical perimeters. SleepCinemaHotel then becomes a performative extension of this predilection, where sleep is seen as essential to the act of viewing—the part that is typically excluded as “unimportant” from a cinematic narrative.

Installation view of SleepCinemaHotel at Postillion Convention Centre, WTC, Rotterdam, 2018. (Image courtesy of Apichatpong Weerasethakul.)

Film theorist Jean Ma has pointed out that sleeping has long been seen as an acquiescent position—as an acceptance of one’s subjective dissolution in dormancy. This shaped much of Western philosophy, and subsequently, (white) psychoanalytic theory. As a result, sleep was seen as foreclosing agency—something that the autonomous subject of the Enlightenment could not admit of itself. Weerasethakul refuses such an absolute conflation of sleep with passivity, looking at dreaming as an active resistance to speed, power and their attendant imperative to produce. Sleeping, then, becomes an act of willful submission to the cinematic apparatus. In fact, sleep has been a widely accepted component of prolonged viewings in the informal economy of living traditions in non-white cultures—such as folk performances in India—which are designed as overnight experiences in makeshift settings. This rejects the notion of sleep as a state of inattention, ascribing it the same value as sensorial alertness.

Installation view of SleepCinemaHotel at Postillion Convention Centre, WTC, Rotterdam, 2018. (Image courtesy of Apichatpong Weerasethakul.)

In the Hotel, the sleeping body attunes itself to the speed of the moving image, while remaining porous to the sounds that permeate its consciousness. Playing in a cavernous space designed to evoke a nautical setting (in keeping with Rotterdam’s status as a port city), the images and sounds create a sleep machine that envelops the body—the ocular shape of the screen further aiding the process in its formal semblance to a portal. Simultaneously a cinema, installation and hotel, this ephemeral experience was curated at a large scale with the specific purpose of inducing somnolence; a “dream book” was also placed for guests in the mornings to record their experiences from the previous night. Through the metaphysical affinity that sleep has been tested to establish across sharing bodies, the filmmaker uses images to curate dreams that escape his own control and form unique experiences of immersion.

Installation view of SleepCinemaHotel at Postillion Convention Centre, WTC, Rotterdam, 2018. (Image courtesy of Apichatpong Weerasethakul.)

All images from SleepCinemaHotel by Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Rotterdam, 2018. Images courtesy of the artist and IFFR.