Classification of the Public Citizenry: Data Institutions in Seismic Vibrato

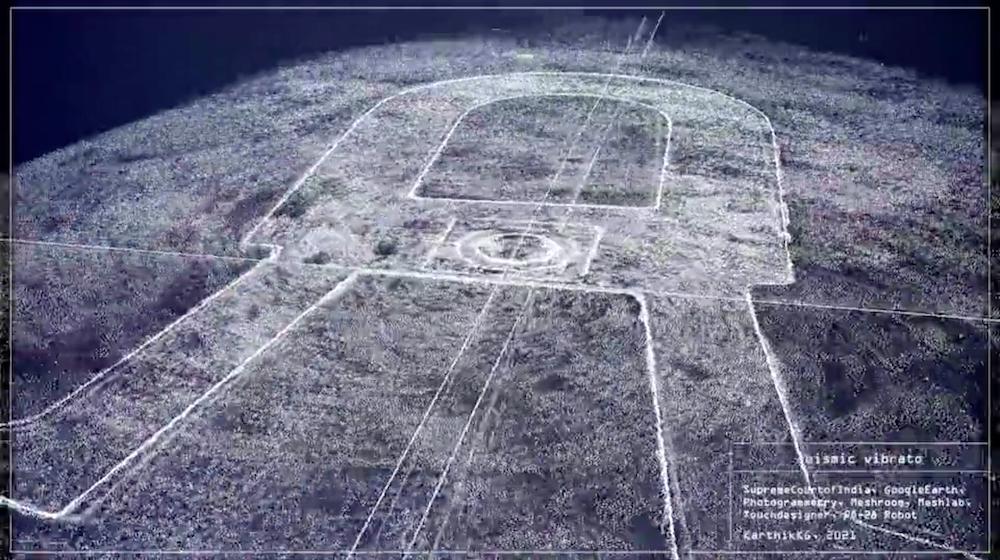

Featured as part of the third week of VAICA’s Fields of Vision under the thematic “Peripheries of the Real,” Karthik KG’s video work Seismic Vibrato (2021) shows a revolving view of a three-dimensional dot model of the Supreme Court of India enmeshed with an eerie 8-bit soundtrack. The dot-cloud model is created through the process of photogrammetry and mesh models of the historic building. Set up in the 1950s, the building was designed by chief architect Ganesh Bhikaji Deolalikar in the Indo-British style. As one of the key facets of India's federal democracy, the Supreme Court stands as a symbol of the secular republic. In an evocation of the power and institutional structures that are seemingly surpassed by the growing pervasiveness of all-encompassing technology, KG’s video work explores each outer manifestation of the building’s structure, while allowing for a contemplation of possible futures.

The title of the work references the musical effect as a component of a dramatic production. Seemingly holographic in its realisation, KG presents a combination of blueprints and a data mapping of the phallic structure, highlighting the fantasy of the masculine state. We see the structure of the sprawling building from below, as a circuitous mesh of points swarm into formation. As a result of this futuristic representation of the institution through the spinning mesh model, one wonders about the prevalence of technological interventions within the criminal justice system. Algorithmic techniques of predictive policing hold a place in the discrimination and subjugation of minorities through the targeting of neighbourhoods that have a supposedly higher crime rates, only serving to lead to further ghettoisation.

While predictive policing based on massive amounts of data analysis of high crime areas has gained some legitimacy in the United States of America, it remains disputed in the subcontinent. Delhi’s CMAPS or Crime Mapping Analytics and Predictive System is known to collect data every three minutes using the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO)’s satellite imageries, in combination with historic crime data. According to a report by the Economic and Political Weekly, the emergency helpline for police is used to identify “crime hotspots.” In the state of Himachal Pradesh, on 1 January 2020, over 19,000 CCTV cameras were installed by the Indian state as a basis for predictive policing, forming a Surveillance Matrix. The states of Telangana and Jharkhand already have predictive policing systems as well.

In another version of this informational matrix, the Hyderabad police are known to use sensitive data from the “Integrated People Information Hub” that contains family details, biometric data, addresses, and even bank transactions, to narrow down people who are more “likely” to commit crimes. In this (mis)use of data analysis and artificial intelligence, what we see is a growing record of the general public through the legitimisation and weaponisation of data as “truth.” Besides matrices of public information that are used to target individuals, social media has also been weaponised by the Indian State to determine public sentiment and ban critical speech. With a murky present of the Supreme Court of India, with its own set of misconduct and scandals, one wonders what the future holds in store for the common citizen.

The disembodied structure in the video dissociates the court from its grandeur and speaks to the unknowability of the speculative futures and the ideals that the institution upholds. KG’s work appears to contemplate the future of the judicial institution and its efficacy in being a harbinger for absolute justice in the face of many players, private and governmental.

To read more about the works featured as part of VAICA’s Fields of Vision, please click here, here, here, here and here.

All images from Seismic Vibrato by Karthik KG. 2021. Image courtesy of the artist and VAICA.