Documenting through Residue: In Conversation with Zishaan Latif

Orchestrated with support from the incumbent government and the police, the pogrom in North-East Delhi in February 2020 followed many months of peaceful protest against the divisive Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) that encouraged legal discrimination against Muslims. Muslim homes and property were demolished and set on fire in various districts in the region by right-wing extremists, while its residents were displaced with severe psychological distress. Photographer Zishaan Latif captured the immediate repercussions on camera, the lack of humans in his frames speaking to a palpable absence and attendant erasure. The frames are instead populated with charred objects, broken glass and other material remnants from the carnage. Almost two years later, Latif retraced his steps to the same places, and captured the sites once again in an attempt to record the failed promises of rehabilitation, ignored FIRs, and psychosomatic diseases that followed the trauma of the violence. His body of work, titled The Art of Hatred: The Aftermath of North-East Delhi Riots, currently showing at the Chennai Photo Biennale, offers a picture of this history through demolished paraphernalia. In the following conversation, Latif reflects on his position as both empathiser and intruder on the scene, the need to document the face of intolerance as it engulfed homes and lives, and the threat to constitutionally-guaranteed equality by the bigoted drive towards exterminating the Other.

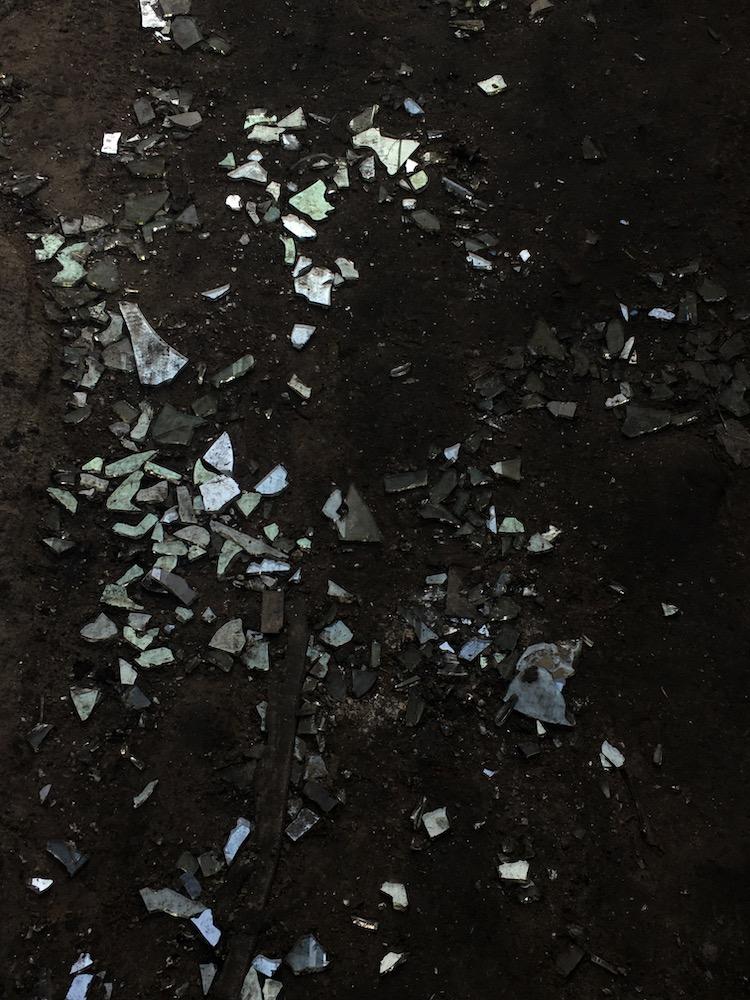

The series was born of these graphic streets, brutal symbols of intolerance; leftover, forgotten. (Delhi, March 2020)

Tiles smashed off the walls of Muslim-owned homes in Shiv Vihar, North-East Delhi. (March 2020.)

Najrin Islam (NI): The NRC and CAA are contentious propositions that have resulted in not only the communal pogrom in question, but also an increased persistence of attacks against minoritised bodies across the country. In capturing the aftermath of the violence across a year, what kinds of intensities and erasures did you witness?

Zishaan Latif (ZL): Intolerance has permeated deeply in many aspects of society, and is perpetuated for politically divisive ends. The riots in North-East Delhi were nothing but a demonstration of this social malaise—an exercise of one’s might over the other. The word “intensities” goes well beyond the ground reality of the Muslim community today. It is actually an understatement for the absolute lawlessness that is exploited by right-wing extremists through the use of Hindutva ideology to make a vulnerable population of Othered bodies. We are already living in a state of an undeclared emergency under the incumbent BJP government. The erasures that occurred during the February 2020 riots were the corrosion of lifelong friendships between neighbours into ugly encounters, and the transition of otherwise harmless salutations like “Ram Ram” and “Jai Shri Ram” into intimidatory threats. If a Muslim does not toe the line, the act of lynching soon follows. Their life is sacrificed in the appeasement of a purportedly larger purpose—that of “re-converting” a secular Bharat into a decidedly “Hindu Rashtra.” This has unfortunately become the premise for the country’s way forward—to robustly establish its “saffron supremacy” at all costs.

I was not a witness to the physical trauma that the residents of Shiv Vihar experienced during the riots, but I felt their fear while walking through the eerie silence that enveloped what were once thriving homes—now palpable triggers that must be inhabited for life. Returning to the site twenty-one months later, in November 2021, was a moving experience. I was able to finally put faces to the charred properties I had photographed in March 2020. Going back for the follow-up chapter was an exercise meant as much for them as it was for me—to know that their story was not forgotten was a solace for both parties. But their battle for justice will always be a foregone conclusion, as it is always an easier institutional manoeuvre to sweep grievances under the carpet than to ensure their rightful place in society.

The remnants of a life destroyed in the streets of Shiv Vihar, North-East Delhi. (March 2020.)

A burnt clock in Gulzar Ahmed’s home; the reminder of a horrific time. (Delhi, March 2020.)

NI: Do you think that the legal validation of anxieties and suspicion around Muslim bodies as predatory agents lends legitimacy to the pejorative construct of the “immigrant” (which is already a remnant of colonial imaginaries around the “border”)? How do you confirm or counter this view through your photographic vocabulary?

ZL: There is an inherent need in my photography to dignify the people I cross paths with and what they represent in this aggressively changing political landscape. It is an instinct to reflect on their psyche, and respect their agency in the choice to be photographed. From the desperation of Bengali-speaking Muslims trying to prove their Indian citizenship in Assam in 2019 to emboldened student protesters marching on the streets of Delhi and Bombay in 2019/20 fighting to repeal the CAA, a collective cause bigger than anything they could ever have comprehended was established. This would eventually help change the course of India’s resilience towards an arrogant authority that set the stage for the famed farmers’ protests, the Delhi riots in 2020, as well as the conditions in Assam in 2021. One could witness in Assam the speed at which Detention Centres, euphemistically labelled “transit homes,” were enrolling those whose names did not make it to the final NRC list of August 2019, and were subsequently stripped of their citizenship status. The last two years have influenced my making as a human being, and brought me to terms with the reality around me, who I am, my name, and what I stand for as an artist—one who is using space and silence to convey the in-between moments of decay in our society.

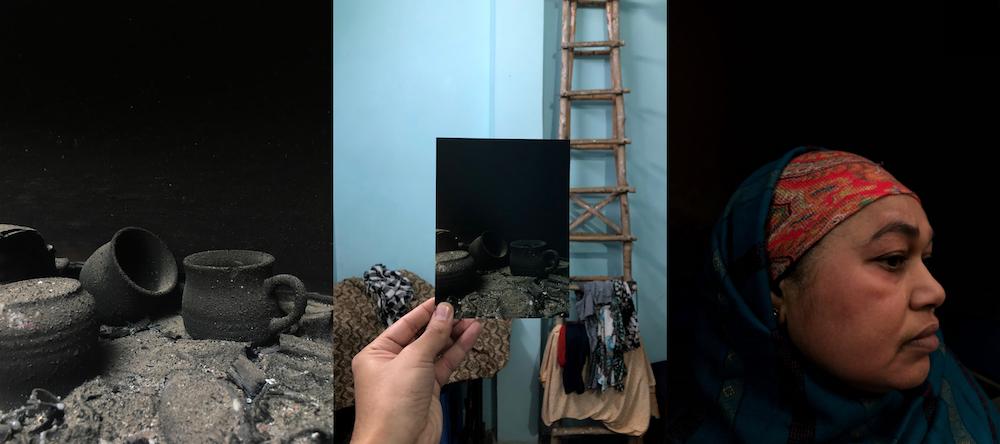

Mohammad Saleem and Husanara’s home―now a constant reminder of the nightmare their family endured during the fatal hours on 24 February 2020―when right-wing nationalists barged into their home, and demanded that they quietly leave without locking up and never return, so that they could do and take what they wanted from the property. Their two daughters were not harmed, but all the savings they had collected in jewellery and cash for both their future weddings was looted before the entire house was burnt down to ashes. (March 2020.)

Burnt pages of the Quran inside the ravaged Madina Masjid. Many places of worship for Muslims were attacked by right-wing fundamentalist Hindu mobs, who were on a mission to show their might in the Shiv Vihar neighbourhood of North-East Delhi. (March 2020.)

NI: How would you describe the precarious cartography of the location that is your subject? As a site of trauma, how much of its weight is visible to a photojournalist such as you? As someone removed from the violence but at perpetual risk of the same, how would you describe your positionality in relation to the project?

ZL: I have a Muslim name and it comes in the equation as a photographer, but this was not the case before 2019. I was forced to delicately navigate my perspective on this world after I travelled to Assam to photograph the plight of Bengali-speaking Muslims, who were trying to prove their Indian citizenship to the Foreign Tribunal. Today, even with my privilege, I feel a depletion of trust all around me, or I could just be paranoid (as my parents say). But this fear is real, and one does not need to have a Muslim name to feel it now—it is an all-pervasive erosion of our secular fabric that everyone can see, but refuse to address out of fear.

If I document any kind of agony, it is because it is present, received and transmuted in ways I perceive personally, as I cannot become immune to human suffering and the destruction of lives. This is not just a fight about Muslims anymore—take, for instance, the continued harassment of Christian minorities every day in many parts of the country by fringe elements. It has become a matter of separating humans through a “us versus them” mindset that entails an essential dehumanisation of the Other. It may be too utopian a thought, but perhaps we can still strive for a world where there is unity, and it is more common than conflict.

Husanara―a wife, mother, riot survivor and now a patient of undiagnosed depression―suffers every day thinking of the horrific days pre- and post the riots, the looting of her home, a near-death experience, losing everything one stood for, and now rebuilding on a shaky foundation with less to no support from the authorities. (Delhi, November 2021.)

All images and captions from the series The Art of Hatred: The Aftermath of North-East Delhi Riots by Zishaan Latif. Images and captions courtesy of the artist and the Chennai Photo Biennale.