Vantage Points of Visibility: An Interview with Vamika Jain

Artist and designer Vamika Jain inquires into the evasive tendencies of visual representation through her photography. Media and its affordances are thus opened up through the landscapes that the artist inhabits and travels across. Addressing the commodification of our visual and social realities, I Travel Therefore I am is a work that expands on a notion of the photographic, analysing the way we register, document and produce visual content to remain relevant. Framing the medium’s current outlandishness and our efforts in retaining repetitive reproductions of the picturesque, Jain foregrounds the image-based inundation that surrounds, as well as defines, our experience of popular tourist destinations today. In conversation with her about this work displayed at the Chennai Photo Biennale, Annalisa Mansukhani explores the tangents that appear in Jain’s experiments with photography.

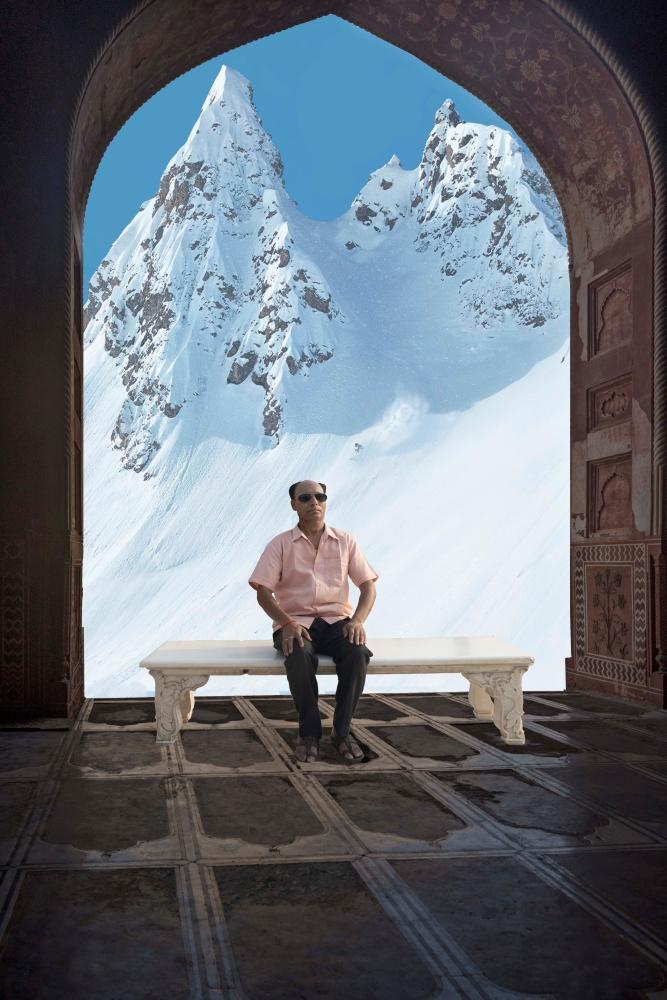

At Taj Mahal, India. (2019. Digital Print on Archival Paper. 28 × 42 inches.)

Annalisa Mansukhani (AM): What sort of a concept of the image do you think this project outlines? How does this project address the idea of something being photographable?

Vamika Jain (VJ): My first memory of taking a photograph is from a family holiday in Shimla. Using a Kodak point-and-shoot film camera, I photographed my parents against a scenic background. With the number of photos limited on film, they were mostly meant for presenting family members in different settings which, once back home, could be developed and shown to guests through photo albums. Although the photographed locations at the tourist destinations remains largely unchanged, the act of photographing them has evolved. Images (including photographs) are now created, looked at and shared by almost everyone around the world. From being visual representations and souvenirs of tourist destinations, the lens has now turned inwards and become representative of society. Images have become a medium to place oneself among popular trends and seek belongingness within a virtual culture. Through the project, I have observed new expressions of this visual aesthetic emerge prominently—everything which can bring validation on social media platforms is now acceptable. Being perpetual image consumers, tourists are recreating photos they have already seen, and hence contributing to an ever-growing pool of similar-looking images online. By means of repetition, addition and elimination of elements from popular images, I identify how and why certain vantage points and cultural signifiers characterise the “perfect” images of their locations.

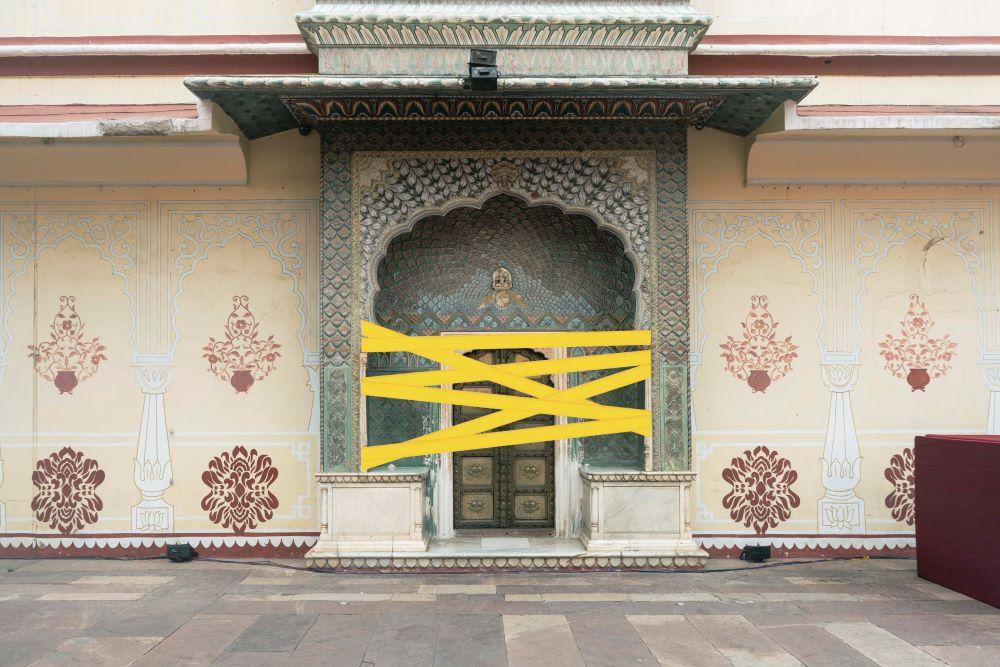

The Royal Palace, Jaipur, India. (2019. Digital Print on Archival Paper. 42 × 28 inches.)

AM: How do the formats of displaying this work accentuate what this project wishes to say?

VJ: The work is conceived as four chapters through photo, video, text and installation. The chapters gather their raw materials from different sources of visual media that discuss tourism. Through scale, placement and materiality, I intend for the project to be an overwhelming and exhausting navigation for the audience. The digitally manipulated images are constructed to invite the audience to contemplate the photographs’ truth and revisit their own visual memory. On Instagram, the presence of similar looking photographs is seen either as a number or few scrolls under a hashtag. Found images from Instagram have been curated as seventy-two sets of nine photographs each, presented as grids. This abundance provides a tangible form to the indefinite tourist images existing online and facilitates the bombardment of visual information.

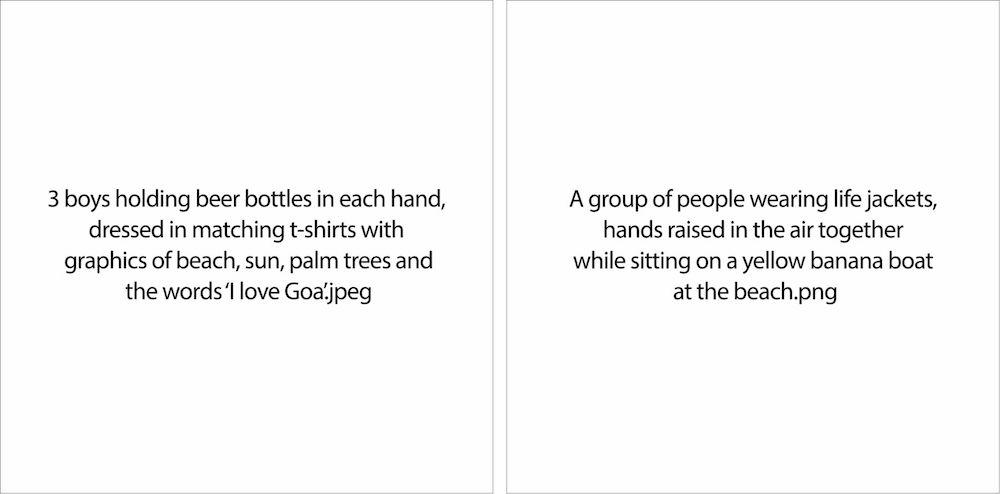

For the last two decades, the social platforms for image display are designed to provide space for text to accompany it. Diary entries from field visits, found texts and excerpts from travel blogs have been created as images, added in image memory to treat its aesthetics and also become elements in the constructed photographs.

2020, Digital Print on Archival Paper. 24 x 24 inches.

AM: What were you seeking to foreground via your experiments with altering the images? What do you think this communicates about the tangibility of a medium like photography when it is translated to the digital?

VJ: At many popular destinations, local photographers—hired to choreograph posing tourists—deliver printed photographs to their clients. Originally meant for family albums, these photos are now re-photographed with phone cameras and uploaded onto social media platforms. With an emphasis on unlimited posts and stories, these platforms have become spaces to store and share slightest details of the vacation. The photos posted here are read with their accompanying texts. Often banal, these repetitive images are now accepted as the standard tourist visuals.

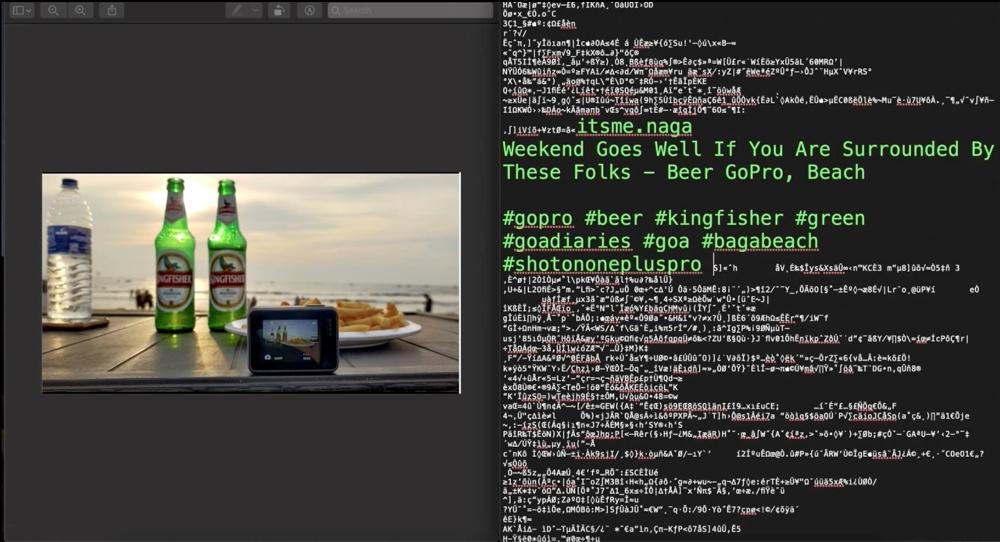

The experiment, displayed as video, becomes a witness to modifying image aesthetics when infused with their captions and hashtags. The texts are akin to veins for these corrupted photographs. While photographs are objects, they are also codes now. It intends to analyse the evolving visual language of images and interpretations of “objectness” of photographs. What makes an online image illegible and invisible—is it the presence of hashtags and captions or their absence?

Screenshot from Video (Colour, 24 minutes.)

AM: Having covered four cities, what future iterations do you envision for this project?

VJ: The project has the possibility to grow in two parallel trajectories. Goa, Agra, Jaipur and Mussoorie—the cities explored in the project have very distinct characters which are unique to them. The similarity in people’s behaviour at these very different destinations has given me insights into the universality of tourist gaze. To comprehend this notion further and to find its footing, I plan to travel to new cities with definite personalities. This will range from places known for pilgrimage to ones entirely dependent on their specific geographical locations. While this will enable me to understand behavioural patterns better, it will also present opportunities to work with new settings and elements composing the cities’ “perfect” images. Alongside, I intend to create new forms of display for the work which cater to my personal dilemma with regard to its tangibility. I also find myself approaching this work through the texts written about tourist locations in travel magazines. The vocabulary and writing style are such that they invoke emotions of escapism. As an extension to the project, I am envisaging forms that will employ these “aspirational” and “influencing” texts in the work.

Visual representation of one grid.

AM: How do you locate this project amid the kinds of questions being asked of photography today?

VJ: In its essence, I see the work as probing the medium of photography and asking the primary question— “Why photograph?” Today, as we are beginning to inquire into the authenticity of photographs in popular media, there is also a need to deconstruct the platforms employed in their circulation. The project mixes fact and fiction to highlight how constant exposure to similar content has made its consumers visually immune to details, as they can be easily distracted. Have photographs created by tourists lost the scope of being iconic and just become “normal”? Through observation of tourist behaviour in different cities, I am trying to identify what drives their constant desire to take photos, the parameters for choosing locations to photograph and the final destination for the images produced. The project interrogates the role of photography as a souvenir of validation in contemporary times. How does the repetition of trend-inspired, similar-looking photographs shape the tourist gaze and, hence, the image of cities? Has Instagram become an ever-growing archive of tourist behaviour in the twenty-first-century?

All images from the series I Travel Therefore I am by Vamika Jain. Images courtesy of the artist and the Chennai Photo Biennale.

To read more about the third edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, please click here.