Fictive Historiographies: In Conversation with Parvathi and Nayantara Nayar

Launched on 9 December 2021, the third edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale titled Maps of Disquiet has brought together a hybrid model of exhibition that “…reflects on the exigencies of our times.” Curated by Arko Datto, Boaz Levin, Kerstin Meincke and Bhooma Padmanabhan, it features the work of thirty-two artists and is open till 6 February 2022. In this interview, Mallika Visvanathan speaks to the artist Parvathi Nayar and researcher and performer Nayantara Nayar about the work “Chicken Run,” as part of their larger project called Limits of Change (2021), which excavates a history of the Korean War through its connection to India. They discuss the drive of the project, their process, and what comes next.

Chicken Run by Parvathi and Nayantara Nayar. (Image courtesy of the artists and Chennai Photo Biennale.)

Mallika Visvanathan (MV): Through the fictional photo-narrative and the re-imagined history writing in “Chicken Run,” you reference a very real archive and past. Can you tell us about what drove you to retelling the Korean War as a moment in history?

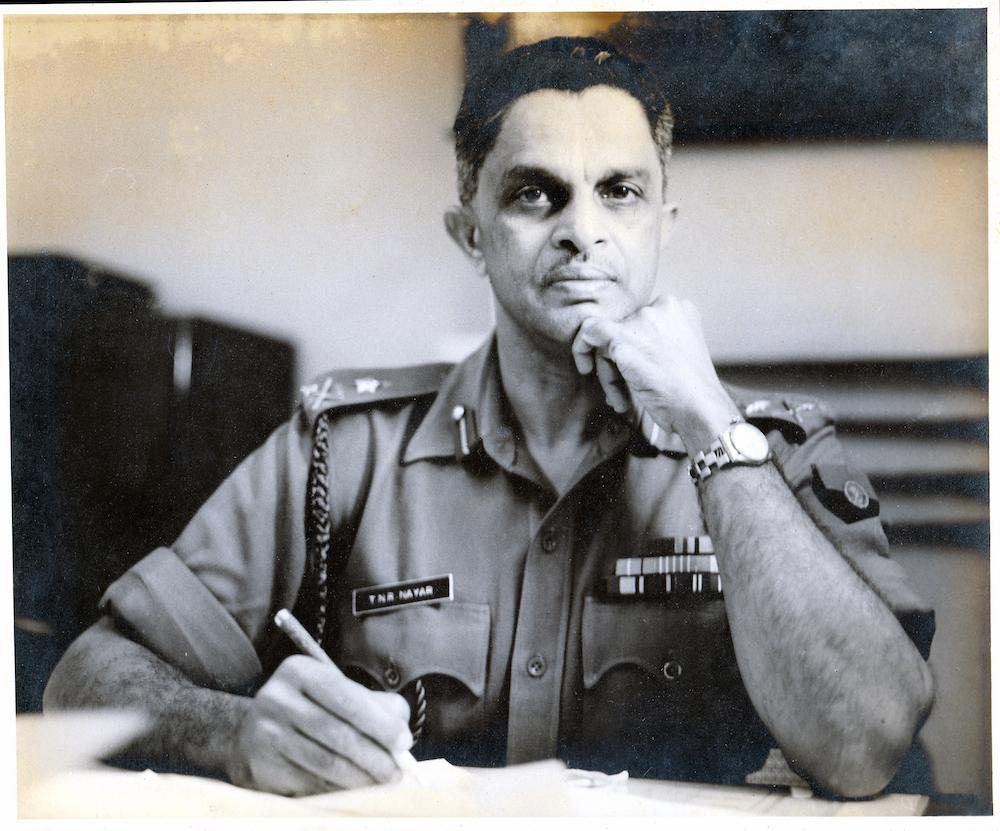

Parvathi Nayar (PN): The emotional centre of “Chicken Run”—hinted at, rather than explicit—is autobiographical. It is based on my father, the late General TNR Nayar’s archives. I was relatively young when my much-beloved father died and left his papers to me. Skip to a few decades later, when I approached my niece, Nayantara, with the idea of a collaborative work based on his words, videos, photographs and memorabilia.

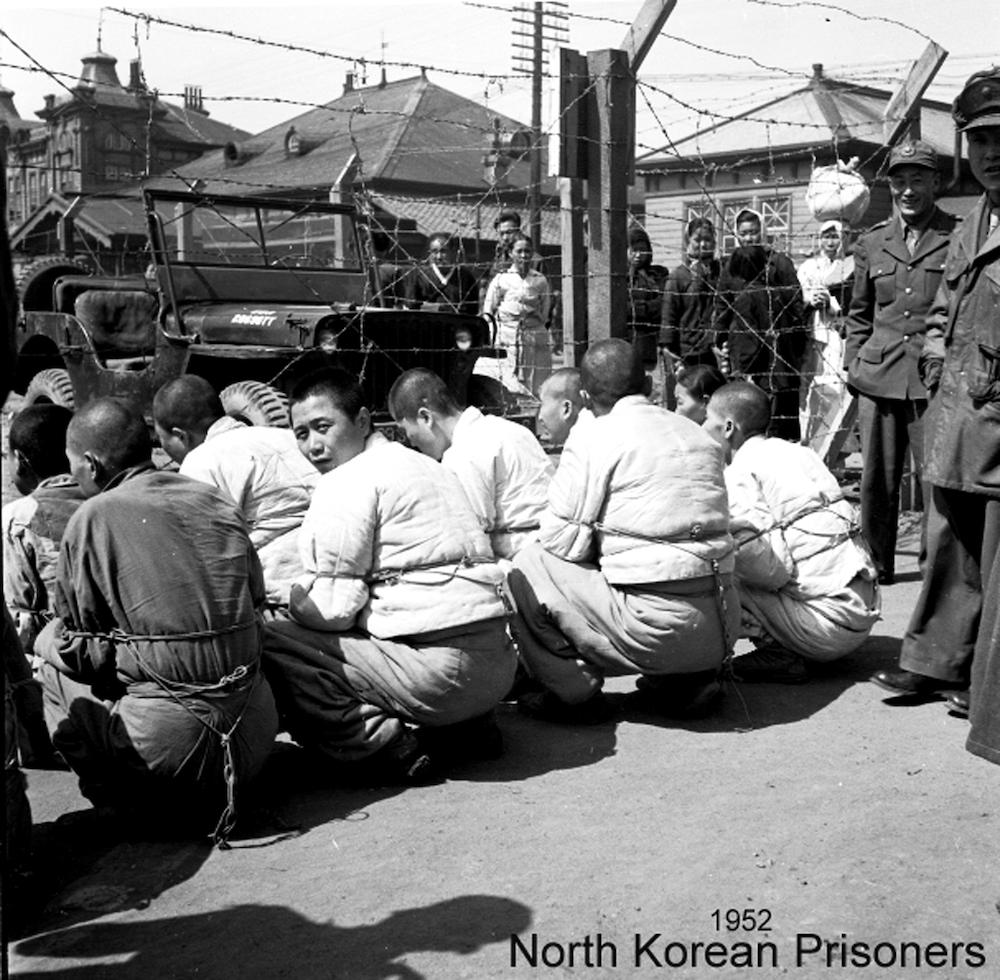

Nayantara Nayar (NN): When we were exploring my grandfather’s papers, we found sections referencing his time in Korea, and later, some photographs and videos. This was interesting because neither of us were aware of India’s involvement in the Korean War. We soon realised it was a largely forgotten section of the Indian Army’s history. The Custodian Force of India (CFI), as the 6000 Indian soldiers sent to Korea were collectively called, were to be both protectors and prison guards for prisoners of war (POWs) who did not want to return home. We thought the idea of soldiers sent on a mission of peace was a concept worth exploring right now.

PN: I wanted to rediscover my father through his life in the army. My father had gone as one of the five officers handpicked by General Thorat on an initial reconnaissance mission to Korea, and then stayed on till the end of the CFI’s time there.

While our initial focus was the CFI, organically, over the course of being housebound in the pandemic, our attention shifted to the Korean POWs whom the CFI had gone to look after. These were POWs who did not want to go back to their home countries. We read about their imprisonment, their time in the demilitarised zone (DMZ) and being watched over by the CFI, then becoming immigrants, making hard choices… which evolved into the story of “Chicken Run.”

Major General TNR Nayar. (From the personal archives of Maj Gen TNR Nayar. Image courtesy of Parvathi Nayar.)

MV: “Chicken Run” has sourced images from not just your family’s personal collection, but from various libraries and archives. Can you please tell us about your research process?

PN: We decided to relook the idea of history—not as the story told by victors, but from the perspective of ordinary people who lived through extraordinary times. From this was born the central structure of “Chicken Run”: Curator P, of the (fictitious) People’s Museum of Chennai, is trying to excavate the story of the mysterious Mr H, a Korean POW who came back with the CFI—when they left Korea in 1954—and eventually moved to Chennai.

Archival images can be incredibly powerful. As Sue Breakell, Archival Director at the University of Brighton, notes, “Archives are traces to which we respond; they are a reflection of ourselves, and our response to them says more about us than the archive itself.”

To expand the archives Curator P is digging into, in order to recreate Mr H’s story, we tried to track down archival images from the Korean War—not an easy process! I spent months chasing leads that ended in dead-ends. However, ultimately, we were fortunate to find libraries such as the Peabody Museum of Harvard, the Pepperdine Collection, and birder photographer Rajiv Kalmadi, all of whom were kind enough to give us permission to use their imagery.

NN: We looked at a lot of different sources of information and images for this project. To begin with, we needed to get a clear understanding of the Korean War itself, so that involved reading authors like Max Hastings and Monica Kim. Simultaneously, we looked for more information about the Indian involvement. There were a few books, but they were hard to track down. We managed to get access to the United Services Institute Library in Delhi, which had some material on India during the Korean War. We also combed through the video and photo archive of the United Nations (UN), because that was where the decision to send the CFI to Korea was made. Despite being one of the most photographed wars of that time, the photos were hard to access and we spent weeks on various online archives sourcing images and writing to ask for permission to use them.

Archival photograph of North Korean Prisoners, 1952. (Copyright Hanson A. Williams, Jr. Collection of Photographs and Negatives, Pepperdine Libraries Special Collections and Archives. Image courtesy of Parvathi Nayar.)

MV: There is a way in which you play with time in this multimedia (text/photo/video) installation. Tell us about how you approached this as a theme and a formal intervention through the project. How does this link to the present moment that we find ourselves in?

NN: The very fact of us having begun with archival material made “time” something we knew we had to work with and against. The project began with a very human urge: to look at the life of someone who is no longer with us. If time machines were real, the project might not exist. But objects and papers can have—with the proper stimulus—an amazing capacity for time travel of a sort. That was what we were interested in unlocking. As we went on, we grew less interested in retreating into some idealised past, and more interested in the resonances the stories we were uncovering had with our time: war, people left homeless and stateless, environmental destruction, divided lands, and a deeply unsettled sense of identity.

PN: Time allows multiple realities to coexist. While we experience time in a seemingly linear way, it changes completely at quantum levels—and also when you have the creative ability to look back on how it loops. That is when you uncover patterns, things that are repeated, truthfully recreated, falsely remembered…

Many of the themes in “Chicken Run”—war, identity, immigration, sustainability, incarceration—continue to be part of our collective, contemporary narrative. We allowed such resonances to be heard, and to play out in registers that were actively felt, rather than enmeshed in nostalgia.

There are certain images embedded in “Chicken Run” that we hope will aid the reception of multiple readings and points of view. Barbed wire, for example, was always both a literal element and metaphor through the ideation of “Chicken Run.” Barbed wire—or what author Alan Krell calls “the Devil’s Rope”—has been effective as a tool of control in war. But, to complicate the issue, it is also used to keep livestock—such as chicken—safe within, while keeping out the wolves.

Chicken Run by Parvathi and Nayantara Nayar. (Image courtesy of the artists and Chennai Photo Biennale.)

MV: Both of you have distinct artistic practices, how has it been to collaborate with one another?

PN: I like that this collaboration has allowed both of us to expand our practices. Our working process was to allow a lot of movement between text and image, history and historically-inflected fiction, archival imagery and archive-influenced recreations. The origins of a narrative idea could begin with me, just as much as a photography frame could be suggested by Nayantara. I think that we have both become confident in different skill sets, apart from the ones we were “known” for when we came into the project. Which is why I think it is true to say that “Chicken Run” is a joint creation in the truest sense of the term—in concept, ideation and resolution.

NN: Speaking for myself, it has been a hugely rewarding, if occasionally challenging process. My aunt is remarkable in her drive and attention to detail, and it is something I aspire to. I have also benefitted from immersing myself in this world of images. That was a challenge, not being able to write myself out of a sticky narrative corner, but as a result I have developed new approaches to writing.

MV: Where do you imagine the future of this project? What other forms shall it take?

NN: Our aim has always been to cover the period of India’s involvement in the war from the perspective of Indian soldiers and Korean POWs. We hope to present our larger project Limits of Change, being produced by the InKo Centre, Chennai, soon. Our current thinking is that it will be a performance + visual art project in a physical venue, but the exact time depends on the COVID situation.

PN: We still hope we can visit Korea and do some research there. In the meanwhile, we have done several talks, a podcast and some video work around the project. A few people have approached us about their associations with the CFI in Korea. So, it would also be fascinating to see if the project leads us to other forms of expressions as well.

At the heart of this project is the thread of that original autobiographical charge we wanted to explore. My father was himself a storyteller who loved art and poetry, and believed in tolerance and fairness. While the project was never meant to be a hagiographic portrait of my father, we still want to find the essence of his history through the truth of our fictions.

Screenshot from Chicken Run, available to view online as part of Chennai Photo Biennale’s Maps of Disquiet.

“Chicken Run” is currently on view till 6 February 2022, as part of Chennai Photo Biennale's Maps of Disquiet.

To read more about the third edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, please click here and here.