Image-Making without the Lens: In Conversation with Srinath Iswaran

Photograms, or “photogenic drawings” (British printmaker William Henry Fox Talbot’s nomenclature), refer to photographic work executed without the use of cameras. Having emerged in various avant-garde contexts in the early 1920s, the process involved placing flora or fauna directly on photosensitive paper and exposing it to a specific light source (often, direct sunlight). A collapse of perspectival realism, the resulting impression of such “cameraless photography” could be perused as form divorced from context—as an exercise in technical machinations in the darkroom. Artist Srinath Iswaran’s work responds to this practice of image-making, where he uses his interest in systems and structures to reinterpret space by playing with contact-exposure.

Light becomes the primary element in the process, its targeted manipulation yielding different optical results. Rendered in monochrome, Iswaran’s series Light Drawings explores the possibilities of pure form, using various intensities of light and its distribution to create multifarious shapes during printing. In the series, Open Systems, the artist explores the liminal space between predetermination and the ambiguity of the outcome, premised on Umberto Eco’s argument in The Open Work that a piece of music is ultimately a gestalt exercise on the part of the listener, despite the control exerted by the composer during its making. In the following conversation, Iswaran talks about creating spatial forms by working against the grain of acquired knowledge, and the nuanced tension between the analogue and the digital that informs his experiments.

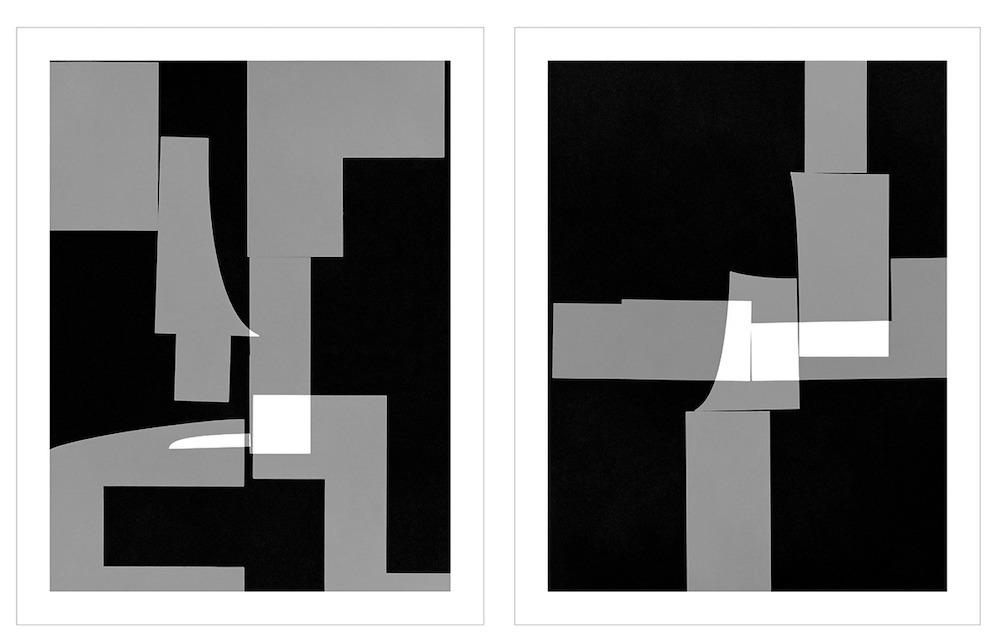

From the series Open Systems. (2010-15. Unique hand printed c-type prints mounted onto 2 millimetre aluminum. 20 × 24 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.)

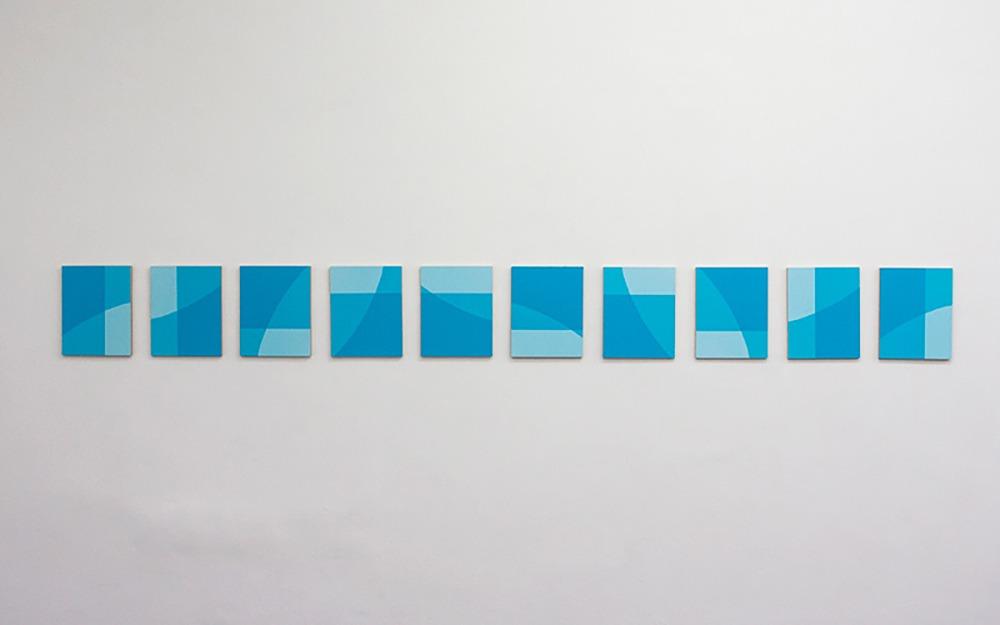

From the series Open Systems. (2010-15. Set of ten unique hand printed c-type prints mounted onto 10 millimetre MDF. 8 × 10 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Najrin Islam (NI): As a contemporary artist, how do you approach the concept of the photogram, and what apparatus do you use to accomplish the intended effects?

Srinath Iswaran (SI): Making photograms helped me understand the materiality of photography better, particularly the way light is captured through photosensitive materials to create an image. I also look at photogram as a form of printmaking that allows me to create a photographic print without the intervention of a camera. The apparatus constitutes an enlarger and photochemicals, and remains a fixed entity in the process. What allows for exploration is actually the materiality of the medium—such as a handcut paper stencil, which can be used in multiple permutations to explore form, shape, rhythm and movement using different filters and exposure points. Photograms help me explore pure form; I am thinking only in terms of shapes, lines and colours, and not objects or the technicalities of their depiction. The process is preceded by acute planning and involves the execution of systematic formulae, but hinges on intuition for completion. It is this contradiction and cohabitation of impulses that interests me.

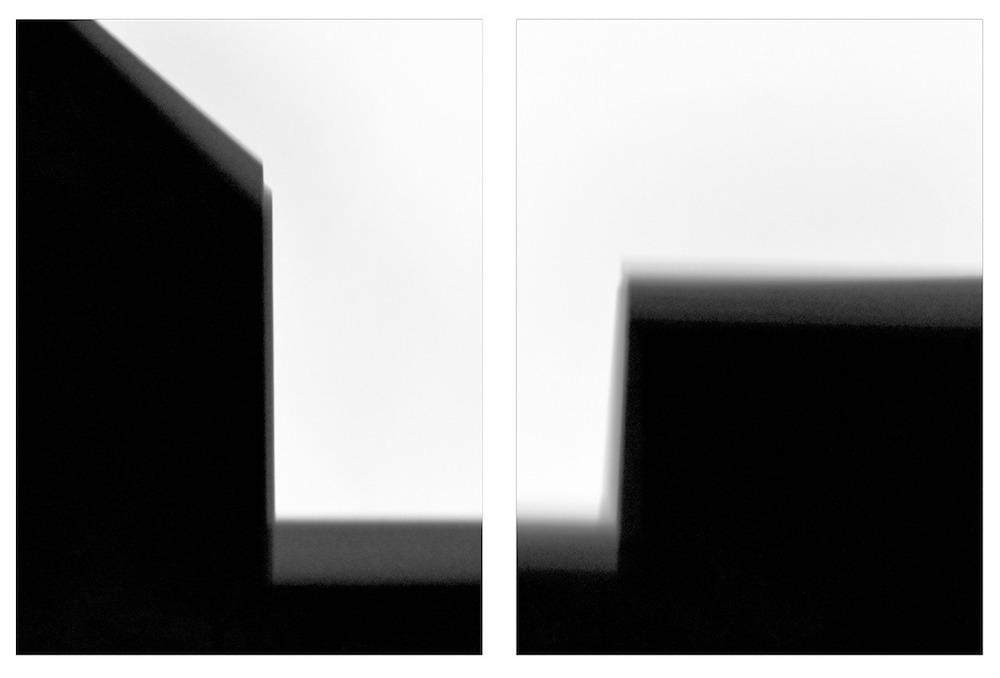

Untitled Diptych I, from the series Light Drawings. (2017. Pigment prints. 18 × 13.2 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.)

From the series Light Drawings. (2017. Set of sixteen pigment prints. 9.6 × 12 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.)

NI: You stated that your focus is on pure form rather than narrative. How do you then address questions of representation, and how does your work occupy this overlap of material registers?

SI: Pure form is traditionally associated with art forms such as sculpture and painting—a notion I wanted to revise through the relatively new medium of photography. The way Concrete artists and Abstract Expressionists have explored the concept further inspired me to work with pure form. A work may resemble a particular form after the culmination of the process, but it is highly subjective, as it was not made with the intent to depict. For instance, one of my photograms evokes the contours of a skyscraper, but any intention in this direction was absent to begin with. Making a stitch or brush mark then leaves space for tangential evocations beyond the immediacy of the process, thus bypassing an objective need to represent.

Furthermore, when drawing, one can see the lines appear as we press pencil on paper, creating strokes to make a form. This interaction between the paper and the pencil in real time is distinct from the making of a photogram, which entails a temporal gap between creating the stroke and the point at which one sees the stroke-mark. This passage of time between the gesture and its formulation rests on calculation, intuition and an experiential memory of the routine in the darkroom—a formative part of photogram-making which, while remaining invisible to the viewer, also carries the weight of the work.

From the series Open Systems. (2010-15. Set of nine unique hand printed c-type prints mounted onto aluminium with thin tray frame. 8 × 10 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.)

NI: Your work is part of a historical lineage of practice that precedes the mediation of the camera, especially avant-garde experiments in the twentieth-century. In exploring the practice through a renewed lens of abstract vocabulary, would you say you straddle the roles of both artist and technician in the darkroom?

SI: Techniques and innovations throughout the history of photography (leading up to the contemporary) have fascinated me tremendously. But I see myself more as an artist than a technician. A technician is one who is well versed with the technology and uses the know-how to produce work of the highest quality possible, i.e., they use the technology for what it is intended. An artist is a rebel in this respect—they absorb but also break the rules, manipulating the mechanics to experiment and create beyond the strict parameters of the machine. As an artist, I understood the supreme importance of light in the making of a photogram, which I subsequently used—not to produce photographs—but to explore pure form in the darkroom. I therefore like to deconstruct a technique and experiment with it in a structured, meaningful way. Historically, photographers like Man Ray worked with the technologies immediately available to them. So, given the times I inhabit, I like to use the digital to see what comes out from its amalgamation with the analogue. This encompasses the use of three-dimensional softwares and laser-cutters to create new bodies of work that traverse the registers of the physical and the virtual, and this is how my politics has been shaped vis-à-vis my position in the lineage of photographic practice.

Untitled Diptych II, from the series Light Drawings (2017. Pigment prints. 18 × 14 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.)

To read more about Cameraless photography, please click here.