Experiments with the Liminal: In Conversation with Rahul Sharma

Professionally engaged in art conservation, Rahul Sharma insists that each medium of photography has its unique grammar and technical relationship with the content, even if the photographer is the primary agent. Technical imaging then becomes a way of using the camera to document and scrutinise—a premise that lends itself well to the practice of conservation. Exploring new avenues such as multispectral imaging technologies, Sharma’s project on the Yamuna River began as a scientific investigation into the health of plants, and mutated over time into an impressionistic body of work around foliage. An exercise in representation, the series explores Delhi’s contentious relationship with the river, which has persisted in a toxic entanglement with the city and its peoples. In the following conversation, Sharma talks about his experiences in the area of art conservation, the meandering trajectories of artistic impulses, and the tactile pleasures of the analogue.

From the series Totems and Altars. (2015-17.)

From the series Totems and Altars. (2015-17.)

Najrin Islam (NI): You work with analogue photographic media and would rather be seen as a hobbyist than a professional. How would you describe this liminal space of interest in imaging technologies?

Rahul Sharma (RS): When I say that I am a hobbyist, or more accurately, an amateur photographer, I draw an arbitrary line between my professional work and the work I do for my own pleasure. They are both priorities, and often overlap or intersect. I have worked as an Assistant Conservator for INTACH in New Delhi, and am currently a postgraduate student of photograph-conservation. I work with my hands, and really engage with the materiality of my subject; it is like having a conversation with the artist/photographer. For example, I conserved a large photograph from Kolkata (circa 1860-70) that was worked on with charcoal. A standard understanding of such a typology would be that these “crayon portraits” were a technical compromise with the available technology at a time when patrons wanted large prints in colour. While working on the photograph, however, I acquired a granular understanding of the print. Details such as the use of wheat paste to attach the photograph to the mount (attendant with an interleaving tissue), or how the charcoal was used to accentuate/diminish tonal planes in the finished image are niche interests. But they gave me an understanding of historical technique, and made me conversant in (and part of) this tradition of image-making.

It is a misunderstanding that digital photography has substituted “traditional” photography; the same sets of visual concerns are simply addressed through different technologies. As a practitioner and part of a photographic tradition, I hope for, and work towards, the persistence of these practices for those that will come after me. Working in the area of conservation perhaps brings more sensitivity to my personal photography. I am grateful to be currently working out of the studio buildings of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, which allows me regular proximity to fantastic art and the ability to engage with it in depth.

From the series Riverlands. (2017-18.)

From the series Riverlands. (2017-18.)

NI: Could you walk us through your project on the Yamuna River, and how you used multispectral imaging to capture its relationship to the city of Delhi?

RS: The conceit of multispectral imaging is pretty simple. One records imaging-data in light, as well as in Infrared Radiation (IR) and Ultraviolet Radiation (UV), which can then be studied and manipulated per one’s requirement. With calibration, one can extract a lot of information about the content of the photograph, as this part of imaging science is well understood. The images of the Yamuna flood plains that I took are not “proper” multispectral captures in this respect; it was more an exploration of multispectral imaging as a creative tool. The foliage takes on a characteristic hue when recorded in IR False colour, which is based on the spectral response of chlorophyll—it can vary from a very strident red to a mellow orange, and the intervening shades. The work I made immediately prior to this was conventional—the images were long exposures of still objects at night, stitched together to make panoramas. It was slow, methodical and deliberate work. I wanted to counterpoint this with something more spontaneous through the Riverland series. Furthermore, performing the “ritual” of scientific experimentation but without the due diligence is something that interests me in terms of making work because it complicates the idea of a photograph as a “technically” neutral medium (its indexicality aside). How does one use scientific practices to complicate a mundane image? The intersection between science and its pretence comes across as an interesting space for interventions.

While creating the multispectral images, I avoided standard procedures in the interest of aesthetic ends—no filtration of light and no standard references. The process yielded its own unique effects from this deliberate irreverence. The original conceit was that I could gauge plant health through technical imaging. The idea was to somehow correlate it—with an environmental objective—to the urbanism of Delhi. The Yamuna flood plains occupy a major part of Delhi (and arguably, define it), but do not really look like the city as one imagines it. This should ideally be the work of one responsible for remote-sensing, or a botanist; I was neither. But I did use the paraphernalia of science to create these images. What does that say about the resulting images, and about me? Not only as a photographer, but also as a person? The images pretend to be scientific data, but they are not. They aim to be pictorial, but are not really traditional pictorial subjects. They are documents of a city, but barely refer to the city itself (except in two frames). They do not hold a narrative, but are set in an order that would suggest one.

I personally think some of them are among the most romantic images I have created (in the art historical sense). But viewers also often tell me that some of them resemble crime scenes. In general, a part of the Yamuna exercise was slightly cynical, in that I wanted to see how much I can run with what initially seemed like a gimmick. But I think that in the four years since I took the images, I look at them in a slightly new light. I think they hold up, and there is definitely an element of playfulness that I now see in the photographs. I would chalk this up to me growing and learning to see.

From the series Riverlands. (2017-18.)

From the series Riverlands. (2017-18.)

NI: You work in the domain of art conservation and restoration—one that also makes use of Infrared Radiation as a means to uncover dormant details. Could you reflect on digital imaging as an important intervention in heritage documentation?

RS: All radiation has energy, which is partially reflected through its wavelength. UV radiation has high energy, and thus, has a short wavelength; while IR has comparatively lower energy and a longer wavelength. One can point UV radiation to a surface and take a photograph, but the ray will bounce off immediately owing to its short wavelength. As a result, the UV image of a surface is replete with its dirt, grime, coatings and fingerprints. In contrast, IR has a longer wavelength, and does not bounce back from the surface. Instead, it penetrates the top layers (depending on the material), and is thus used to image such details as the underdrawings of paintings, i.e., otherwise inaccessible underlying layers. Multispectral imaging can thus give one the superhuman ability to see that which cannot be seen otherwise.

As an optical tool, the camera has the unique ability to reveal, and gets more interesting as a formal medium in its potential to further render the invisible visible. The camera creates a record of an object that makes more apparent the context, history and all the things we care about with regard to heritage. When the photograph becomes a tool for investigation, we create information by interacting with and changing the intrinsic nature of the photograph; the line between the subject and the image, then, diffuses. Often, a lot of the investigation is done algorithmically. There is still a connection between the subject and the image, but by this time, the final iteration does not look anything like the original image. For example, I undertook a project which used machine-learning algorithms to study colour distributions in hand-coloured photographs from nineteenth-century Japan. I started off with “normal” photographs, but by the end of the research, I was working with “images” that were ten discrete channels of data, none of which looked like their originals.

What, then, is multispectral imaging in the context of conservation, or for that matter, an “artistic practice”? At one level, you are creating a document that contains actionable information about, say, a hidden signature or an underpainting. It can also indicate the presence of specific colourants. Of course, they should be treated with suspicion and viewed critically, as all images should. At the same time, it is a cheap tool with a low footprint that can be conveniently mobilised in third-world economies. My colleagues regularly travel up to remote monasteries in Leh to document wall paintings with kits such as this. It also allows an easy way to communicate the respective stories to the general public—an area that art conservation often struggles with owing to its esoteric practices.

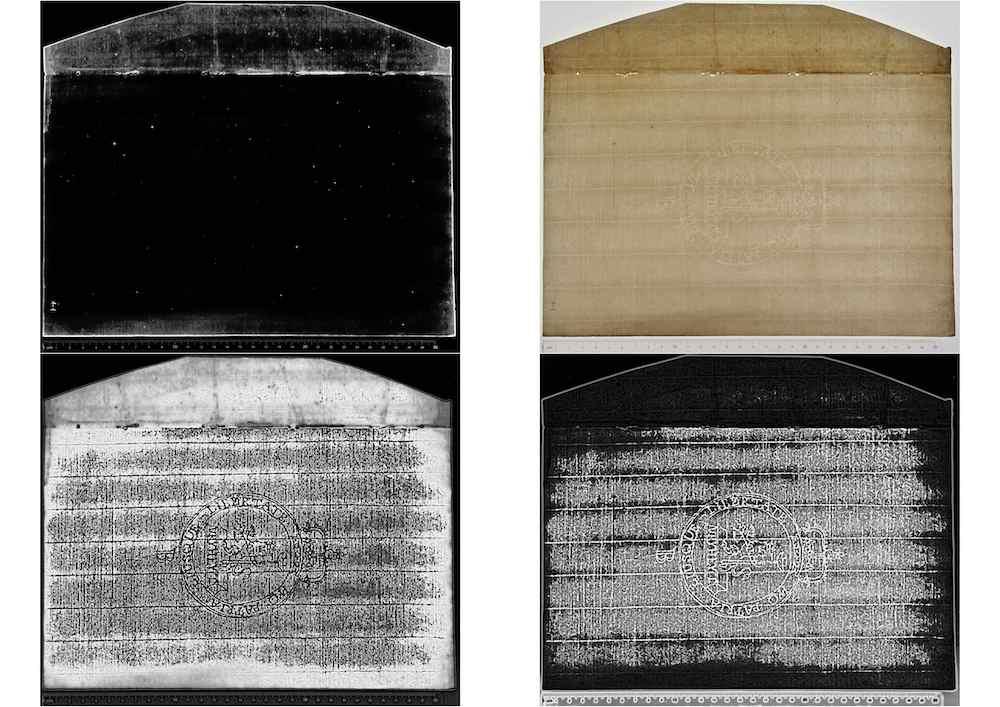

This is a transmission image of a seventeenth-century handmade paper envelope. The original image was algorithmically converted into three optical density images (i.e. separated into three images based on how much light it blocked).

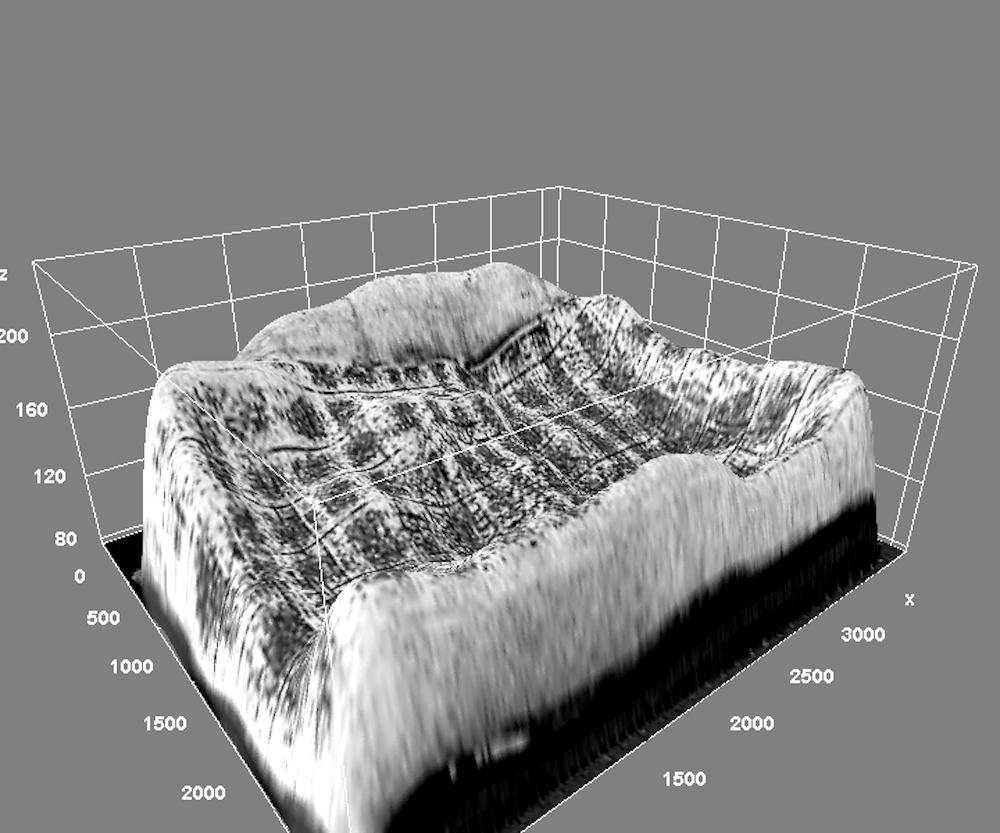

The above was then plotted into a Contour Plot (that allows one to visualise three-dimensional data in a two-dimensional plot) to reveal the difference in the thickness of the paper over the sheet. The final iteration thus departed from the original photograph while still containing actionable information.

All images by Rahul Sharma. Images courtesy of the artist.