Analogue Retellings: In Conversation with Ashish Sahoo

Engaged with film photography, Ashish Sahoo’s work is situated in the intimate experiments of the dark room. The medium and the content are intricately connected, and each serves the other in the production of alternative vocabularies for traditional narratives. The fragility of ambrotype glass plates, for instance, is used in the service of a series that explores the tenuous political modes of governance along religious lines. Sahoo’s work gravitates towards foregrounding that which is vulnerable to disuse or disappearance—realised through concentration in dilated time. In focus is the series, Narrative Flux, which explores these registers with the aid of the Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography, 2018. In the following conversation, the photographer talks about process, context and generic crossovers, as well as how his images are sutured in and activated by interactions between the epic, the personal and the analogue.

Narrative-Flux Part-1. (2018-19. Ambrotype.)

Narrative-Flux Part-1. (2018-19. Ambrotype.)

Najrin Islam (NI): Your practice of analogue photography engages strongly with performative storytelling as a mode and trigger. What role does the staging of the participating bodies play in rescripting traditional narratives?

Ashish Sahoo (AS): Most of my work derives from traditional performative acts such as the Ram Leela, or dance forms such as the Purulia Chauu and Odissi. They depict formative mythological stories that have persisted through oral retellings. As the narratives have mutated through reception across the country, I started to question their relevance in light of their mobilisation by political agents in the contemporary moment. In the Narrative-Flux series, the first thing I did was conduct research on the multiple, extant versions of the Ramayana—the starting point being the essay, “Three Hundred Ramayanas” by AK Ramanujan. After that, I collaborated with writer Sourabh Harihar to create a new script by distilling the insights of the multifarious versions, and formulating them in the styles of the Valmiki and Kamba Ramayanam (the epic’s Sanskrit and Tamil iterations respectively). This is the precise point where the reinterpretation of the text began.

I collaborated with performers (theatre actors for the ambrotype plates and Chauu dancers for the silver gelatin prints) who participate in traditional stagings of the Ram Leela, and subsequently worked on the script for a month. In this script, I completely changed the characters from how they are usually played by the actors. Through this collaboration, I attempted to not only deconstruct the particular narrative through my photographic vocabulary, but also approach the performative act anew through their bodies to reconstruct said narrative. So the performers became the medium through which I explored my queries and urgencies. They engaged in a remoulding of the characters by dismantling their traditional, familiar portrayals, thus partaking in my queries as well.

Narrative-Flux Part-2. (2018-19. Silver Gelatin Print.)

Narrative-Flux Part-2. (2018-19. Silver Gelatin Print.)

NI: The series, Flesh and Wound, makes a compelling use of material hybridity to foreground an immediate political urgency. Could you walk us through the process and impulse for this work?

AS: In 2014, the new right-wing government came to power, and—in their imposition of conservative Hindu ideology—put a blanket ban on the circulation of beef in the market. The ban was intended to make criminals of those who sold or consumed beef, and was targeted specifically at the Muslim community for their identity and dietary practices. The government’s decision resulted in a rise of self-proclaimed “cow vigilantes” who illegitimately surveilled and attacked members of said community, going largely by stereotypical understandings of their look and attire. During these times, I visited Mehrauli (a locality where I bought my meat) more often, and discussed the political climate with the local butchers. I heard them address their fear of living in this country with the identity they have and the business they are into; their livelihood was under threat. They insisted that this is only the beginning, and that “They are banning beef today, tomorrow they will ban us”—a rhetoric we have witnessed being realised through the implementation of the NRC and CAA in 2019.

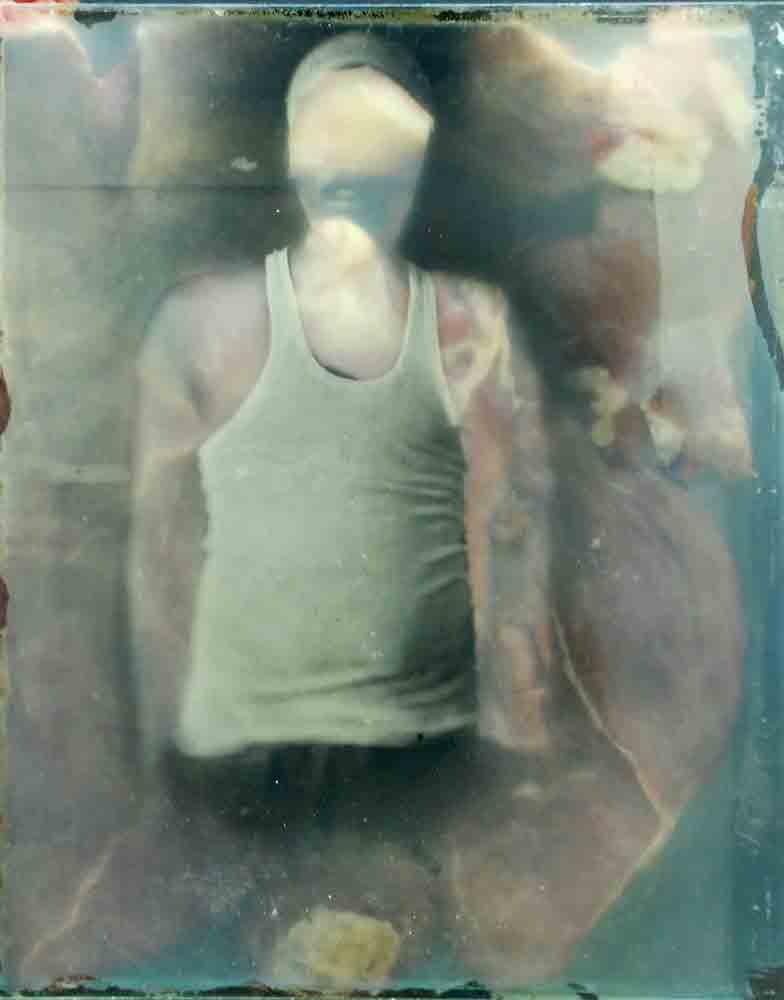

So, in Flesh and Wound, I invited the butchers I most interacted with to my studio, and shot their portraits with my large format camera using the wet plate collodion process. I wanted to focus on the materiality of the glass positive as a metaphor for my message. So, before varnishing the plates, I scratched out the parts in the portraits where the subjects’ skin was visible in order to shift attention to their attire—the resultant effect was a ghost image. I then placed actual meat behind the scratched-out parts on the glass plates so that its texture replaced the absent faces, substituting the subject with the object in context.

Flesh and Wound. (2015. Wet Plate Collodion Glass Positive.)

Flesh and Wound. (2015. Wet Plate Collodion Glass Positive.)

NI: The portrait is an important visual component in your oeuvre. You have created portraits both literally and in absentia—such as the tombs of colonial officers in the Park Street Cemetery, Kolkata. How is the traditional mode of portraiture in dialogue with the alternative photographic processes in your work?

AS: The alternative photographic processes have their unique characteristics, and are always a part of my decision-making process around a project. I like to create deep and structured layers in my work. I am always inclined towards theatrical aspects, so lighting and staging become paramount. When we talk about photographic portraiture, it mainly refers to capturing the emotion, character, identity or personality of the subject before the camera itself. In my work, however, I create my characters with an idea of identity as it is shaped through my performer-subjects. It is in this durational process of identity-reconstruction that I find the characteristics of alternative photographic techniques prescient. It works as a curtain on the subject’s personality, and brings out the essence of the character they portray, or which I intend for them to portray—and this includes the architecture in the Park Street Cemetery as well.

The Burden of Identity. (2019. Gum Oil Print.)

All images by Ashish Sahoo. Images courtesy of the artist.