A Voyage in Time: Rajee Samarasinghe’s If I Were Any Further Away I’d Be Closer to Home

Rajee Samarasinghe is a Sri Lankan visual artist and filmmaker who left his island-country in 1998 at the age of ten, when the civil war was underway for about fifteen years already, and settled in the United States of America. Following his graduation from California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in 2016, he has made several experimental films that employ hybrid forms of the aural and the visual to communicate his ongoing struggle with framing the memories of his homeland, the place of his “origins”. If the word comes across as too mythic, or even sacred, it is because it’s a function of Samarasinghe’s narrative style, which deliberately uses technological manipulation and asynchronous methods of recording and filming to stage his own play of the memory of landscape and family. In this regard, one could re-purpose American filmmaker James Benning’s idea of landscape being a function of time, to suggest that it is also a function of memory. Benning continues to teach at CalArts, so his influence is visible in Samarasinghe’s work, including his attraction for Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. Thoreau’s book provides the concept of a bubble-like space, a clearing in the mind, within which a natural landscape can be claimed personally and granted significance for one’s own struggles of emergence as a body in a landscape.

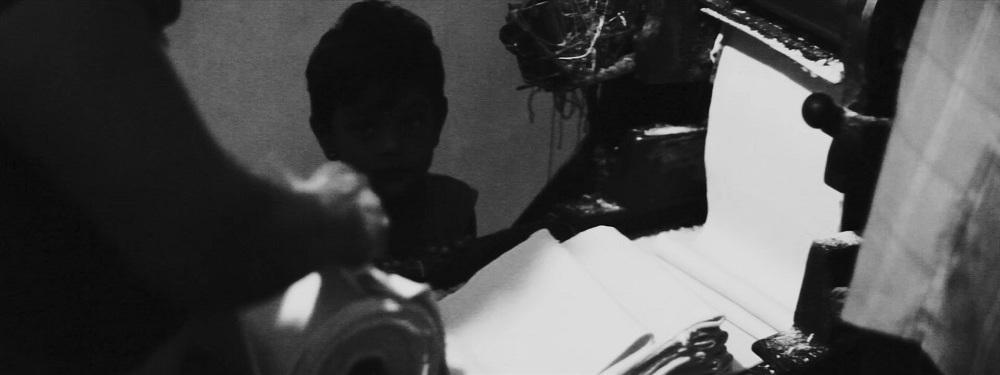

If I Were Any Further Away I’d Be Closer to Home (2010-16) impressionistically follows the routine of labourers in Samarasinghe’s mother’s place of birth in Sri Lanka. The film follows their activities, looking to find a congruence in the materiality of these past lives in the equipment of film itself. The latter becomes a machine for memory-making, as projector reels are rhymed with the making of noodles, threads of light get trapped by dust. The muted sound ensures a singularity of attention to the whole tableau so that we don’t hear the guttural whirr of the old anamorphic projector lens that has been hitched on to a digital camera. These manipulations are meant to signal the exploration of seemingly paradoxical, counter-intuitive methods on film, a revered process within avant-garde cinema: breaking up the structural pattern of realistic narrative to strengthen its claim on realism, or revealing the complex technological games that are involved in producing any smooth, aesthetically satisfying document of memory.

Samarasinghe writes about the violence that structures memory and image-consumption for someone growing up in a war-torn country:

“One of my earliest memories is of burnt human flesh in newspaper halftones wrapped around a breakfast pastry purchased for me by my mother at the local marketplace. I can remember associating the flesh with the smell of bread which made me ill—though it did make me aware of a certain logic that had to do with pictures. In 1983, Prabhakaran rallied his band of rebels and civil war was declared in Sri Lanka. What rose was a culture saturated with analogous images of pain...”

His memory of the halftone is hardly a reassuring, nostalgic image of bliss and could partly explain his choice for the black-and-white frames for this film as well. Emerging out of a context of the all-pervading power of the analogue image in crafting national trauma, Samarasinghe’s choice of the digital medium appears not just as a way to tell stories differently, but to engage in the material terms of memory itself through other means—other strategies even—that can communicate the traumatic implications of a reality that is never quite past even when it is muted, controlled and its appearance of wholeness shown up for being little more than an arbitrary pattern of dots.

All images from If I Were Any Further Away I’d Be Closer to Home by Rajee Samarasinghe. Sri Lanka/ USA, 2010-16. Images courtesy of the artist.