Sacred Unveilings: Sepideh Farsi’s 7 Veils

Nothing confirms the inherent savagery of an entire community than an act of destroying artistic or cultural property, as global liberal opinion is inclined to believe unanimously. In her 2017 documentary 7 Veils, Iranian filmmaker Sepideh Farsi carries a fairly straightforward agenda, if the film needs to be reduced to one: that of peeling the layers of perceptual violence that afflicts a country, distorts its voices and manipulates its image for the world outside.

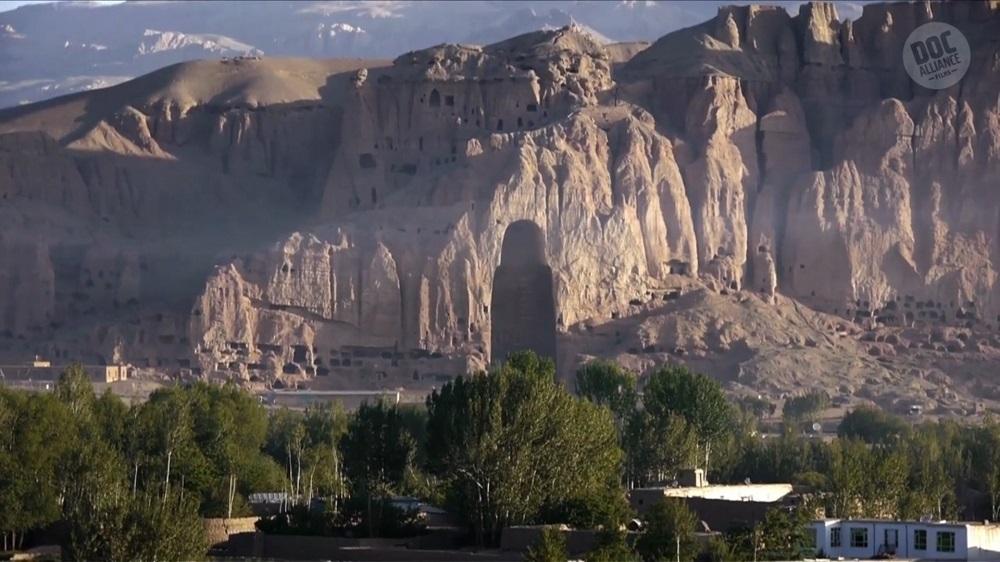

With 7 Veils, Farsi turns her gaze towards Afghanistan, a country marred by war and strife since decades. For a country that is treated as a stubborn site of resistance to Western influence—even at the cost of increasing brutality and ethnic tension within its borders—the film serves to qualify these clichés with its own casual ethnography of local voices, revealing a range of contexts, resistance and acute political understanding that can easily elude the casual observer. In this film, the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddha statues by the Taliban in 2001 forms an important centerpiece. Farsi probes local reactions to the vandalism and excavates wider sites of resistance in the country, thereby allowing the global audience a privileged view behind the veil of such an enormous act of destruction and its stereotypical implications. By doing so, she reveals the hyper-visible tropes that conceal the ordinary, everyday life of the community which is rooted in acts of political resistance and viewing their own country’s cultural heritage differently.

The film starts with Farsi recounting a folk historical account of the Bamiyan Buddhas:

“It is said that Salsal, the great idol of Bamiyan, was hidden behind seven veils. Seven thin veils. Through which his body could be seen in a silk gown. He had a huge gem on his forehead. At dawn, when the crowd would gather to pray, as the sun would rise from the Iron King Mount, the veils would be taken away so that the sun would light the gem. And the gem would shine so much that the people would only see the light, and no more the Buddha. They would say it is God, and would worship him.”

This story, prevalent largely among the Hazara community, becomes a metaphor for the elusive, but forbidding, state of Afghanistan itself—including the complex changes in its history as it transitioned from the early idol-worshipping indigenous populations who made up its polity to its increasing homogeneity under Islam.

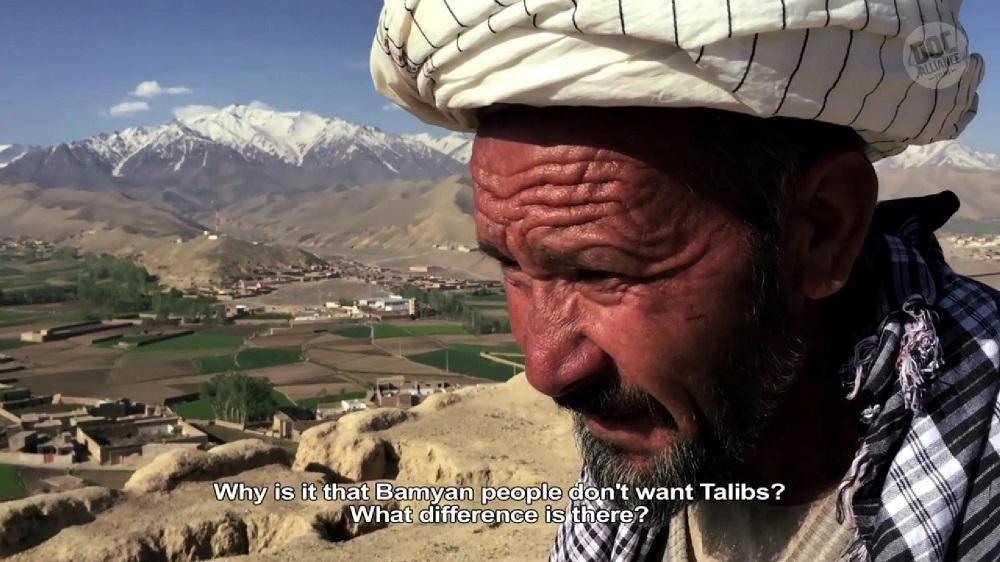

Bamiyan is also located along the historic Silk Road, which has been an agent of change and migration, reflecting an inherent diversity in the region, whether expressed in terms of ethnic differences or inter- and intra-religious differences. It is strongly implied by Farsi—and the men and women of Bamiyan that she speaks to—that if those Buddha statues could be given a local identity it would have to “belong” to the Hazaras. The Hazara people in and around Bamiyan are strongly aware what sets them apart from other Afghans, not only in terms of culture and language but also facial features, which are closer to the model depicted on the statues. The destruction of the idols thus provoked a major reaction from the Hazaras, and they recount proudly how the Taliban has struggled historically to control their region or even recruit from within their population. There is also a clear understanding of the political stakes involved in defining themselves as “separate” from other Afghans as national culture is taken here to be a euphemism for modern Taliban rule rather than a simple encapsulation of their collective past.

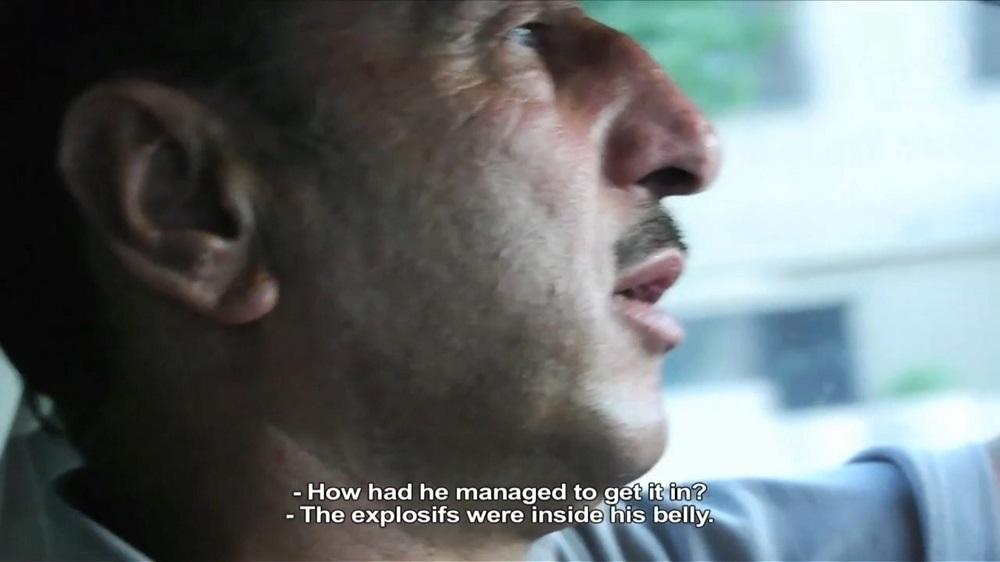

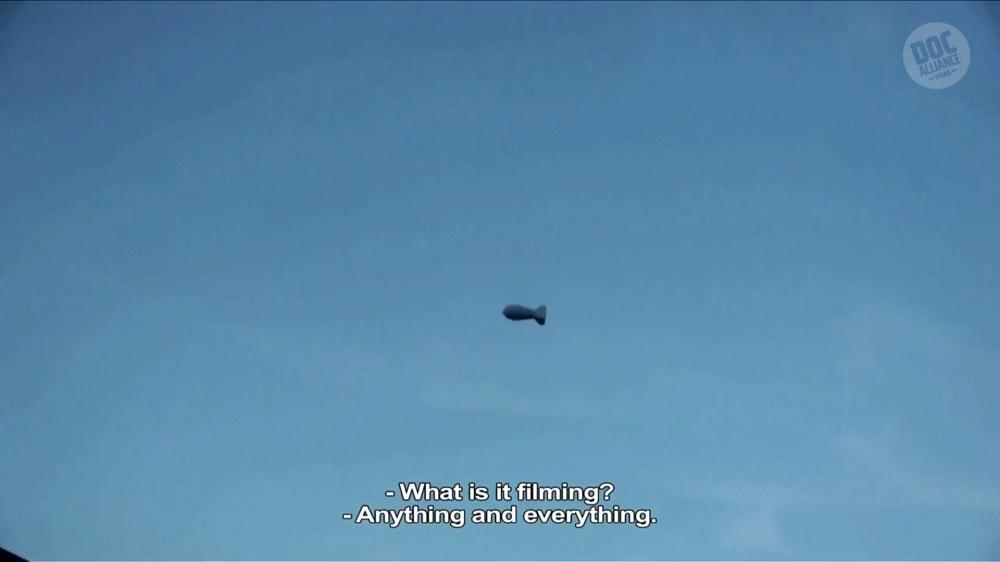

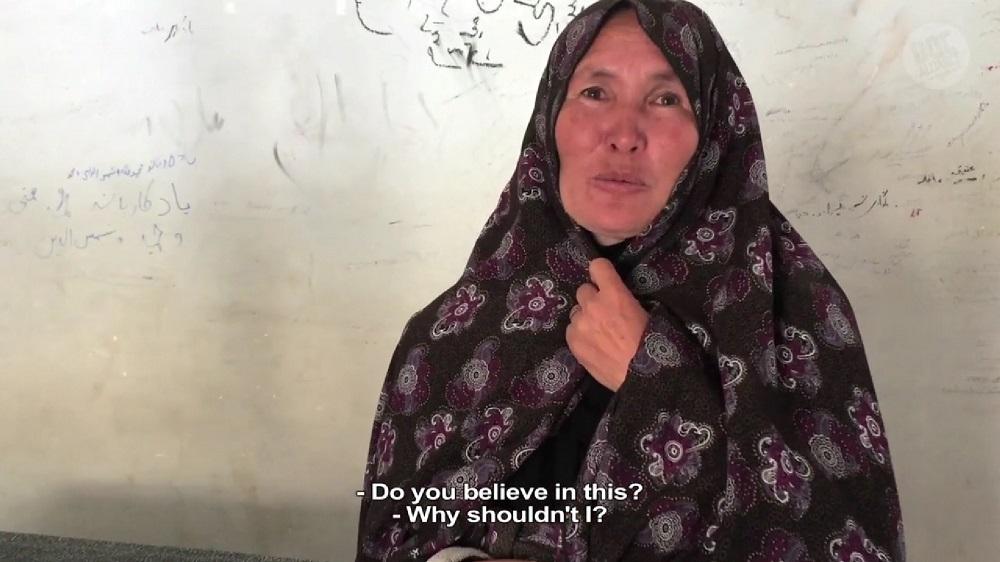

The speech of the Afghan people in the film is also a matter for complex unveiling. Due to the paranoid security state that existed in Afghanistan even before its recent ‘liberation’ from American (and NATO) occupation, people are reluctant to offer the clarity of their own understanding of their region, choosing to conceal their opinions behind the screen of performative ignorance or elaborate forms of local knowledge, obscure to the casual viewer. Even among the ‘other’ Afghans that Farsi speaks to in and around the French embassy in Kabul, there is a clear sense of an absence of political authority in their own hands. Instead, the manifestation of the paranoid state is signalled by the presence of drones and a large set of eyes that appear to be vigilant, on the lookout for threats to peace and rooting out corruption. The government backed by the NATO troops was widely seen to be corrupt by the people of Afghanistan and it is cited as one of the major factors leading to their embrace of the puritanical, incorruptibly anti-Western, Taliban, instead.

These layers are unveiled to offer a glimpse into what absence of autonomy can look like for an entire country and how impossibly distant the prospect of freedom could be. Looking at it the right way is the beginning of knowledge about Afghanistan for the world. Farsi’s documentation of the sinister drone cameras operating over Kabul and the country at large only multiplies the many ways in which the perception of the country gets framed and appropriated. The work of unveiling that the documentary performs is painstakingly undertaken. It is the film’s achievement, ultimately, to show how much labour is required on the part of an audience too, to look beyond the screen of the first image that presents itself.

All images from 7 Veils by Sepideh Farsi. Afghanistan/ France, 2017. Images courtesy of the artist.