Fishing for Utopia: Dharmasena Pathiraja’s The Wasps are Here

The Asian Film Archive spent several months restoring the damaged reels of The Wasps are Here by Dharmasena Pathiraja, leading to its special screening in the Classics section of the Cannes Film Festival, 2020. (Image Courtesy of Asian Film Archive.)

Along with Lester James Peries, Dharmasena Pathiraja was a part of the small group of filmmakers who were translating the radical potential of social revolution onto Sri Lanka’s cinematic narratives in the 1970s. Following the country’s independence from British rule in 1948, a series of socialist governments had tried to harness the populist enthusiasm of the new island-nation until, Pathiraja explains in an interview, the “Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) or People's Liberation Front led by educated but unemployed youths mounted an armed insurrection to overthrow the government in April, 1971.” The insurrection was crushed brutally, leading to several deaths and a rising sense of frustration among the youth who looked towards new economic opportunities in growing urban centres such as Colombo. Some of Pathiraja’s early films including Ahas Gauwa (1974) and Eya Dan Loku Lamayek (1975) examine the consequences of these movements and labour migrations into the cities. Bambaru Avith (The Wasps are Here, 1978), however, looks at a related, almost contrary phenomena: the impact of westernised, urban modernities as they encroach upon the lives of rural, isolated communities such as the one shown in Kalpitiya, a small fishing village in the north-western part of Sri Lanka.

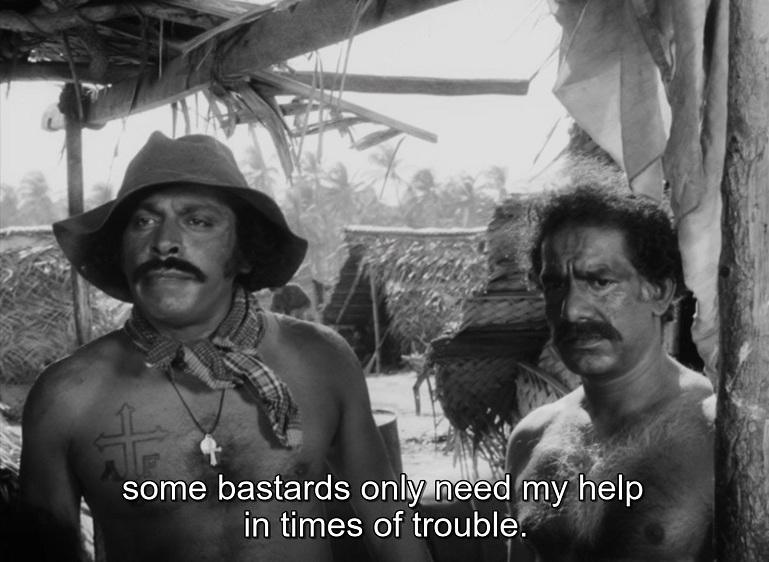

In this film, painstakingly restored from extremely damaged negatives by the Asian Film Archive, we are introduced to a small Christian fishing community whose economy and way of life is disrupted by the arrival of a group of urban sophisticates, led by the “Little Master,” Victor. Victor’s father used to be a well-respected and powerful member of the community before he left for the city, severing all ties in effect, even though the villagers still feel a sense of reverence towards him and his son. Victor uses this awe to manoeuvre himself into the local economy of fishing, enforcing auctions and other changes in their practices of selling and hoarding, and edging out the reigning controller of this economy: Anton. Elsewhere, he also sets his eyes upon Helen, a girl he had known in his childhood before leaving for the city. Even though she is engaged to be married to her childhood friend Cyril, she too falls for the charm of the young man from the city, with his fashionable bell-bottoms, perfectly coiffed facial hair and taste in rock-and-roll music. Soon, things come to a head: Victor’s business manipulations are resented by Anton and his cohorts, and his consensual affair with Helen provokes a violent breach of peace as bodies begin to pile up.

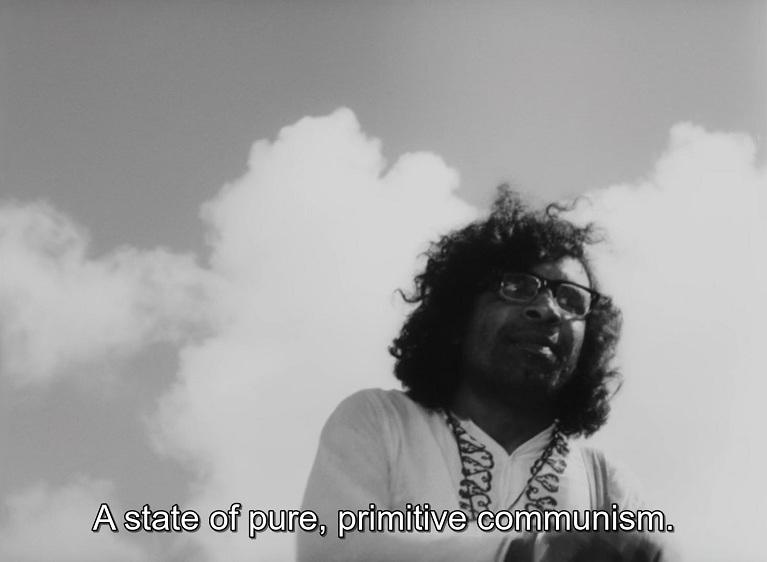

It is to Pathiraja’s credit that the narrative does not take any obvious stance. Victor’s attempts to disrupt the community’s economy of life is resented not just by a few locals but also by Weera, his Marxist friend from the city, who rails against the abstract violence of his friend’s methods, which is more powerful and scarring than the mere physical conflicts started by the drunken locals at night. But Weera’s efforts are also shown to be inadequate, if not farcical. If he has used a tool to engage the audience’s critical reading of the film, this tool is shown to be a useless one in the end as his great oration, exhorting the people to rise up against exploitation by the big-city entrepreneurs, is delivered to an empty patch of earth, his audience having left midway. He idealises the community in the mould of a noble savage (or a “state of pure, primitive communism,” as he puts it) who have the power to make a new beginning, a new community of equals that is free from the depredations of capitalist modernity. But by the late 1970s, this vision had clearly exhausted itself and fails to engage anybody. He takes a bus and leaves for the city, disenchanted.

The film’s narrative has a mythic quality; a simple conflict of modernity and tradition is converted into a story of forcible co-habitation and tragic progress. Victor might be well-meaning in his efforts to regulate the local fisheries and Helen is far from regretful about the choices she makes but their actions have tragic consequences for the community, and cannot be undone. Allegorically, the fate of an isolated community surrounded by predatory capital speaks to the larger anxieties of Sri Lanka too. The film’s restoration (and easy availability on streaming platforms like MUBI) is worthy of celebration as it makes accessible a valuable aesthetic moment from Sri Lanka’s history of poetic, social realist cinema.

All screengrabs from The Wasps are Here by Dharmasena Pathiraja. Sri Lanka, 1978. Images courtesy of the artist.