Teaching a New Art: Transitioning to the National College of Arts, Lahore

Gateway to the National College of Arts, Lahore. (Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Following the Partition of former British India and the concomitant birth of a new, bifurcated nation-state in 1947, Pakistan was warming up to the demand for a new agenda in the arts. The way it was taught, practised and integrated into the social life of the newly imagined community of East and West Pakistani citizens—divided by landscape, culture and language—was foremost on the agenda of planners and developers of the new state.

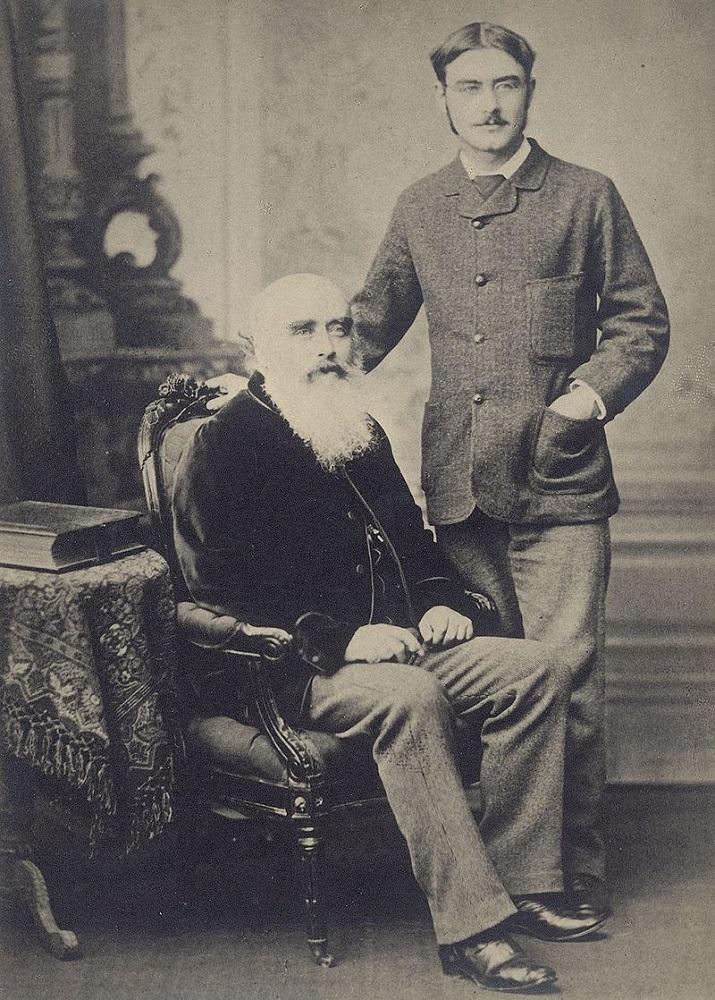

If East Pakistan saw the opening of new schools like the Dhaka Art School—currently known as the Faculty of Fine Art—in 1948, led by figures such as painters Zainul Abedin and Anwarul Haque, for West Pakistan the impetus was provided by an older, colonial institution that was made to transition into a new era. The Mayo School of Industrial Arts in Lahore was founded in 1875, partly in reaction to the late Victorian Arts and Crafts Movement, and was led by the vision of its first principal, John Lockwood Kipling. After the foundation of Pakistan, however, it soon became the National College of Arts (NCA) in the late 1950s. The institution’s Lahore residence was a point of convergence in artistic and cultural agendas with state-planning and development goals for a nation that relied on the rapid industrialisation of its economy.

The first Principal of the Mayo School of Industrial Arts and curator of the Lahore Museum, John Lockwood Kipling (seated), seen here with his son, Rudyard, who would use the Museum as an inspiration for the Ajaib ghar (Wonder House) in his well-known novel Kim (1901). (Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

These arts and crafts institutions were meant to be educational spaces to engender a more homogenous, repeatable method and practice for creating new art and design for a modern economy. But the story of its transition from the Mayo School to the NCA is a narrative of progressive change and evolution, one that is performed at various levels, in tandem with cultural forces across the world, rather than the heightened political factors informing their immediate contexts. At times, polemical, stark binaries were made to assume by artists and pedagogues invested in these administrative locations. However, a more nuanced narrative has been told over the years to recognise the nature of its true influence on the arts and crafts of Pakistan and its eventual divergence from the stated goals of its founders and early administrator-artists.

Shakir Ali, the famous painter and former Principal of the NCA, regularly emphasised the newly re-fashioned institute’s postcolonial agenda to be different from the colonial, sociological purposes of the older institute. In this new vision, the practice and signification of ‘craft’ had to be quietly done away with for its allegedly backward connotations, suggesting a “folk,” pre-industrial essence that had little place in the thinking about modern and contemporary art. Anthropologist Nadeem Omar Tarar writes,

“In the modernisation discourses of the Pakistani state, ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’ became emblems of transitional stages of national cultural development. The project of modernity spurred the national imagination as colonialism was recast as an unfinished project of modernity, leaving room for a renewed agenda for the progress and development of a modern nation.”

The Alhamra Arts Council, Lahore, designed by Nayyar Ali Dada. Dada was one of the foremost modernist architects of Pakistan, as well as being a graduate and teacher at the National College of Arts, Lahore. He was also a close friend of Shakir Ali. (Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

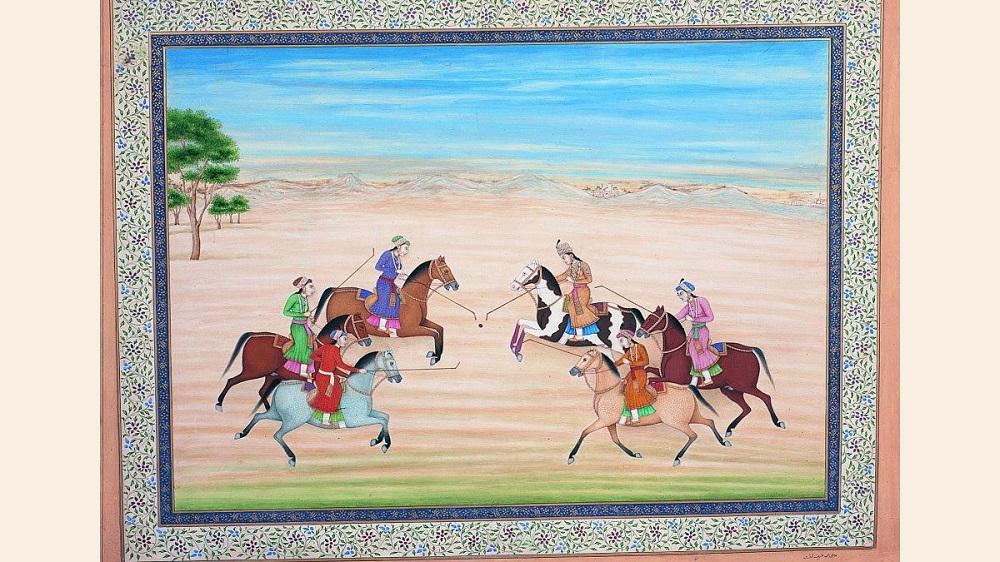

This is not to suggest that all traditional practices were rejected; they were simply recast in different terms, their prerogatives framed separately from their original contexts of labour and community, so that they could be made to aspire toward a new kind of civic or communal ideal. In this instance, Tarar mentions the case of Haji Muhammad Sharif who was brought on to teach in 1951, largely for his renown as a miniaturist. Since miniature painting was considered a traditional practice and the artist had no formal teaching degrees, his salary was on par with a lecturer even though he had joined at the age of sixty. As Tarar notes, “His lifetime experience could not earn him professional status equal to an art school educated artist, in a field in which he was celebrated over three generations of known ‘hereditary’ miniature painters.” Thus, the new institution, instead of practising a radical postcolonial politics of self-assertion, was frequently beholden to Euro-American orbits of merit or guidance (usually preferring teachers with “foreign” degrees), both intellectual and financial, in the quest for legitimacy.

A miniature by Haji Muhammad Sharif. (Image Courtesy of S. M. Mansoor and Ruby Lal Photo Gallery.)

To the institution’s credit, however, its early models of internationalist influence were not always in thrall to the extractive economies of Western modes of production. They were, in fact, mindful of reacting against those same tendencies. The foremost influence on the NCA’s founders was the Bauhaus school, which ran for a brief but influential period in Weimar Germany before the Second World War broke out. The Arts and Crafts Movement itself was an organised reaction to the rapid industrialisation of Britain. Thus, traditional ornamental styles and workforces could be given a new lease of life, and a space crafted for them in emergent discourses of aesthetic taste. The alliance between the Harvard Advisory Group —influenced by Walter Gropius’ presence at the time at the University’s Institute of Design—and Pakistan’s Central Planning Commission reflected these goals. In the first objective report written by the administrator “reformer” Mark Sponenburgh in 1958-59, he hearkened back to the ideals of both Bauhaus and the Arts and Crafts Movements, writing:

“This institution seeks to go beyond technical instruction by placing emphasis on creative thought and action and to develop in students an awareness of this essential unity of the visual arts both traditional and contemporary. In this respect, the National College of Arts is similar to the Bauhaus school where effort was made to integrate industry and visual arts in a harmonious whole.”

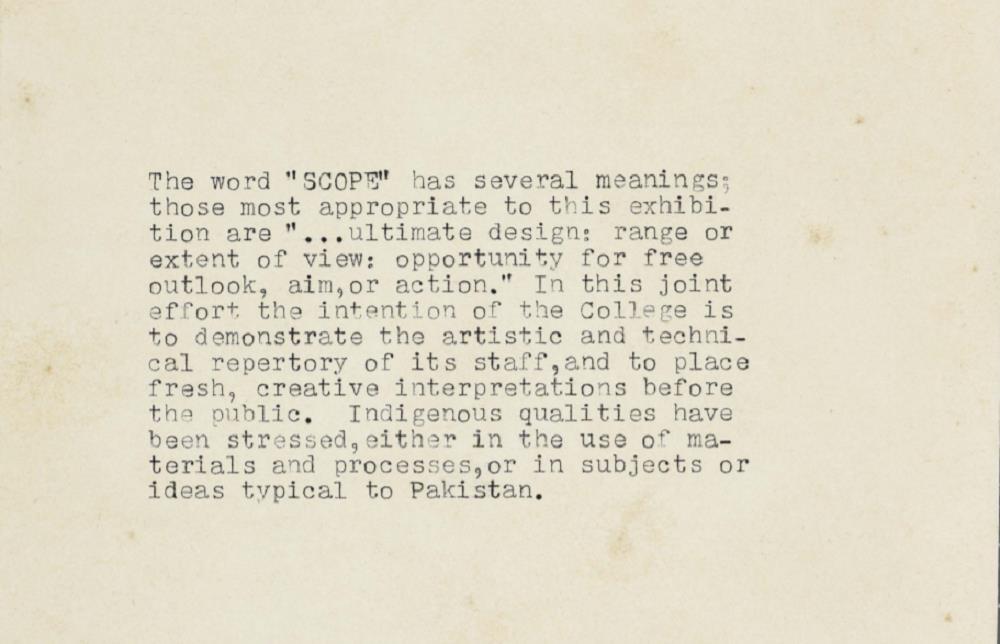

Extract from a leaflet prepared by faculty members of the NCA; their efforts at defining an agenda took multiple dimensions of traditional craft and modern design discourses and brought them together to construct a popular aesthetic standard. (Scope. Lahore: National College of Arts, 1960. Image courtesy of Asia Art Archive.)

Eventually, however, with the philosophical and pedagogical interventions made by several generations of artists and administrators at the NCA, including Shakir Ali, whose influence was formative in founding, ironically enough, a “tradition of the modern,” as the art critic Akbar Naqvi once put it, were directed towards dissolving the socialist impulses implied in the Bauhaus pedagogy for preparing a better skilled workforce for industry and mass consumption. Tarar cites a greater degree of success for a school like the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, in following those principles.

As he (Tarar) writes,

“Sponenburgh’s strong inclination towards serving industry through art and design education disappeared in the context of the post-colonial identity politics of nationalism and modernisation in a postmodern economic world. Its founding objectives based on the principles of the Bauhaus, intending it to serve the purpose of learning and educating the rural and urban worker were passed over, as by the middle of 1960s, modern artists, largely comprised of the first generation of NCA graduates began to look elsewhere for inspiration and critique.”

While this suggests an institutional context for practices in Pakistani modern art, it also goes a long way towards narrating the career of the radical, socialist-secular principles that underwrote artistic programmes in the early postcolonial world of South Asia and their eventual fall from grace.

Leaflet of a group exhibition of the works by the faculty members from the National College of Arts, Lahore. (Scope. Lahore: National College of Arts, 1960. Image courtesy of Asia Art Archive.)