Between Motion and Stillness: In Conversation with Priyank Gothwal

The practice of visual artist Priyank Gothwal occupies an intermediary position between the possibilities of still and moving images. His work deals with existential experiences along with culturally contextualising the ideas of time and its effects on beings and spaces. In an attempt to conjure alternative forms that counter and decolonise the modern order of time, he investigates how historicity influences the daily lives of common people.

Stills from Sugar Bowl. The work attempts to create an indexical mapping of Sri Lanka's colonial history and its tumultuous relationship with sugar production by combining stillness and motion in an affective study of minutiae and mundanity. (Priyank Gothwal. Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2018. Single-channel video, 20 minutes. Images courtesy of the artist.)

As a persistent effort to re-read and re-present the performance(s) of time in our everyday lives, Priyank Gothwal brings together a vast body of references that further his evolving critique of late capitalism and mass popular culture. His practice remains in dialogue with the affect of contemplative cinema, in the vein of the work of filmmakers such as Roy Andersson, Lav Diaz, Yasujirō Ozu, Andrei Tarkovsky, Béla Tarr and several others. In this conversation with Annalisa Mansukhani, Gothwal reflects upon how his practice resists acceleration and linearity and the ways in which his mediums of choice communicate his experiments with the abstract concepts of time, space and being.

Annalisa Mansukhani (AM): Over the past few years your practice has come to accumulate works that incorporate both still and moving images as a means of illuminating ideas and experiments that revolve around the notions of time and space. How did you arrive at such an intersection of themes and lens-based media?

Priyank Gothwal (PG): I would rather say that over the past few years I have worked in between the mediums of still and moving images. I was certain from the beginning that I did not wish to particularise the object of my interest within my practice out of a fear of grabbing a flat absolute. After a while I realised that what interests me potentially exists within the continuum and the averageness of the everyday, placed in relation to the things that surround it while gradually changing with time. In the early phases of my master's degree, I could identify with this time-savvy medium of the lens as convenient enough to indicate and frame everyday life as an evolving entity. However, I wanted to use this medium in a way that truly depicted the mundanities—the “this,” “here” and “now,” the infra-ordinary moment that can be seen existing in between stasis and motion simultaneously. I found myself at an intersection of themes where I had to excavate a conceptual intermediary space/position in between still and moving images.

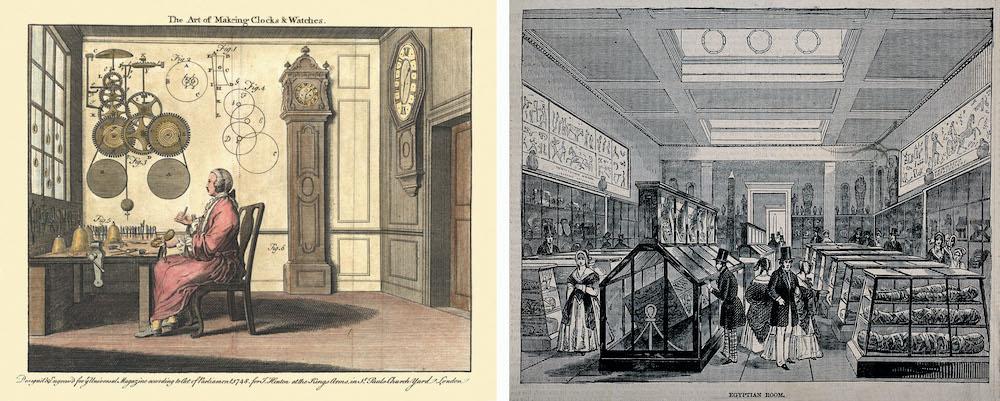

Left: The art of making clocks and watches. Right: The Egyptian Room of the British Museum, London. Wood engraving, 1847. (Images courtesy of Wellcome Library, London.)

AM: You have consistently woven elements of cultural critique into your practice, focusing on the ills of capitalist mass culture, especially references from writings on history, politics, philosophy, poetry and cultural studies. Could you tell us about how your mediums of choice record and, subsequently, supplement such critique, in keeping with the abstract forms of some of these concepts?

PG: Over a certain period I learned that what I was dealing with was the abstract notion of time which can be seen as a continuum of [the] “now”. Time can be seen as a structure of dimensions—the past, the present and the future—all of which are differentiated by a situated consciousness within them. I would call this a concrete concept of time. This in itself would make time a political site, according it a beingness with actions within its discourse to catalogue and categorise its structures and progression. It would also be able to use the ability to historicise as a tool to dominate others.

The element of cultural critique in my practice developed gradually. I would say it needs more work so as to attain a certain maturity, by learning new perspectives about the concept of time. In order to understand the effects of capitalist mass culture on the way we currently understand time, one would have to dig deep into the history of temporality itself. According to the Australian historian Giordano Nanni, it begins in Europe with a new monastic order and the rising need of a separate time-discipline and consciousness. The invention of clocks, Sabbaths, the seven-day week and the writing of history forged an effective artificial, temporal identity in order to prevent one from getting lost in the eternity of time and space.

This was then furthered by the rise of imperialism and colonisation in different parts of the world, where colonies created trivial binaries of time and timelessness, the regular and the irregular, the historical and the ahistorical, and so forth. These concepts fit well with the need to come up with a singular, governing, temporal world order that sought to establish synchronic agreements between the minds of the capitalists and the hands of the workers across the globe. The most unequivocal outcome emerged in 1884 with the official deployment of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), a centralised, standardised notion of time. The entire concept of time here is tethered to the idea of global capitalism. The German philosopher Theodor Adorno said that even the notion of spare time in today’s late capitalist order is shackled with its opposition, i.e., the temperaments of work and production. I try to criticise this historical, modern regime of time in my practice by intervening with the ideas of incommensurability, infinity, slowness, boredom, procrastination, worklessness, mundanity and states of reverie. I envision my practice as incorporating such attempts to epistemically decolonise the tyranny of the mechanised clock and this destitute order of time.

The Cactus Lover. This work involves the long, durational act of continuously filming a saguaro cactus pot for fifteen days in order to witness a 00.1mm growth. (Priyank Gothwal. What About Art Residency, Mumbai, 2018. Fifteen-days-long double-channel video installation. Images courtesy of the artist.)

AM: It's interesting to note that your works create and engender several oppositions—formats of infinity, slowness and ungraspability are harnessed to counter ideas of acceleration, capitalist time and commensurable space—that articulate the vocabulary you have built around your practice. What does the play of such oppositions translate into for you?

PG: In the span of a few years, I have started placing my art practice somewhere within the domain of applied sociology. This permits me to expand disciplinary boundaries to a level that it produces applicable artistic visions that attend to particular issues in their historical settings. It engenders the concept of opposition as a tool to show alternatives and to produce resistance. To create an opposition is to create an object of immanent resistance against the malign that surrounds it—in this case, the order of capitalistic time—rather than just generating a transcendental critique of it. Hence, formats of infinity produce a resistance towards the tendencies of commensurate time and space; formats of slowness resist the cultures of acceleration or paced-up societies and so on.

AM: Your methods of making images often entail interventions into the materiality and scale of the images themselves. This conveys the weight of duration in understandings of time and the stretchability of distance as catalysing the expanse of a space. Do these interventions and methods become commentaries on the capacities of the mediums themselves?

PG: Yes, these methods do become commentaries on the capacities of the mediums. I think my intervention to stretch an image in time in some of my works is only possible because of the temporal malleability of the mediums I use. Roland Barthes [in his book Camera Lucida] once said “What the Photograph reproduces to infinity has occurred only once: the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially."

Hence, the medium inherently possesses the capacity to endure time and intervene in it. Additionally, it depends on the way one expands the contours of the acquired medium, using it against the grain to affirmatively sabotage the historical and political legacy of the apparatus itself. That is only another way of saying that a medium is as good as it can be when its capacities are stretched from time to time. I have attempted to make this visible in one of my works, Images of distances (2016-17), where I try to slightly alter the internal mechanism of the apparatus to plot a fictional narrative of looking far out into space, mapping geographies and time and reiterating histories by referencing historically documented images from around the world. Due to the capacity of the medium that allows it to bend, this work could depict a unique phenomenon of reciprocal recognition, achieved between these historical images and their spectators, all the while being present across two different temporalities.

Left: Images of distances. (Priyank Gothwal. 2016-17. A series of eleven images.) Right: Srinagar, Kashmir. (Henri Cartier-Bresson. 1948.) Priyank’s work was manifested within the surrounding fence of the Shiv Nadar University campus, by pointing the camera towards the referred locations of old documented images. (Images courtesy of the artists.)

AM: The motif of the mundane is repeated across several of your works, particularly those located in observing and documenting the lives of public and semi-public spaces. Furthermore, within this texture of the everyday, you have explored the relationship between mapping geographies and the passage of time as well as looked at the nuances of boredom, mortality and life. As the finished works often entail an intimate and patient viewership, how do you place the engagement of the viewer with the concepts that you explore?

PG: My works often demand intimate and patient viewership as many of them incorporate long-durational engagement and intricate—almost elusive—details in time which can be difficult to endure or notice. I have works which are twenty-four hours long, such as 10:58pm (2017), and fifteen days long, like The Cactus lover (2018) as video installations. In such cases, the intention is to load the viewers with the density of time, and sometimes to not only test the capacity of viewers but also to produce something which exists to indicate the infra-ordinary in the present moment. I try to make the virtual time within the work move in synchronicity with the viewers’ breathing time. Even if they disconnect out of exhaustion and rejoin later, they find the work ageing with them. This temporal connection between the work and its viewers tries to highlight the nuances of boredom and mortality in life.

Stills from Sátántangó. The film opens with what is its longest shot, spanning eight minutes. It features a herd of cattle moving out of a village, that has been abandoned and sold off by the villagers. Time is hence used to explain the villagers’ dire circumstances. (Béla Tarr. Hungary, 1994. 7 hours, 30 minutes. Images courtesy of the artist.)

AM: How do the different formats of presentation that you have used—photobooks, video installations, photo essays—affect the consumption of your work?

PG: The role of different formats of presentation is to facilitate the content of the work to its spectators. However, the affectivity of each format reflects differently onto the reception of the work. For instance, a photobook is a format where one can take control over the temporal progression of the images, indulging in intimate and haptic relations with the work. For me, it helps to diminish the aura of the work. Similarly, the format of a video installation has allowed me to sculpt the motion of time in a manner where it can become an object. This enables me to hold on to an intermediary position where motion and stasis are blurred together and become interchangeable, which is the inherent conceptual need of my practice. Every format adds a unique quality, and opens up a different prospect to any experience of the content of the works.