The Labour of Politics: Filming the Aftermath of a Political Victory in Kush Badhwar’s Work Starts Now

The Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) was founded by K. Chandrashekar Rao in 2001. He intended for it to be a political platform that could deliver the promise of a separate Telangana state, carved out of the larger, extant state of Andhra Pradesh, with Hyderabad as its capital city. After more than a decade of contentious campaigning, hunger strikes and participating in the carousel-ride of coalition politics (with national outfits like the Congress-led, United Progressive Alliance), Rao was elected the first chief minister of the newly formed state of Telangana in June 2014. As most political observers in India know very well, hard distinctions between mass cultural appeal and mass political appeal are drawn at one’s own peril. Aside from the usual political tactics, therefore, Rao co-opted movies into his propaganda schemes. He wrote a song for the film Jai Bolo Telangana (Hail Telangana!, 2011) and for some of his poll campaigns as well. Filmmaker Kush Badhwar’s video Work Starts Now (2014) attempts to telescope the two domains of influence through the lens of labour—the kind of work that goes behind the construction of political rallies and the almost gentle camaraderie that presides over their dismantling.

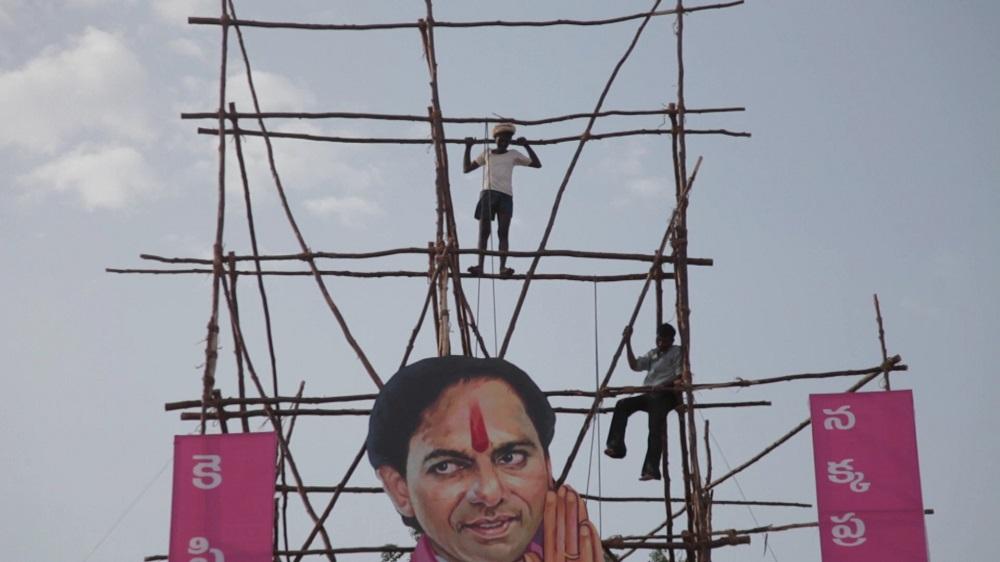

While Badhwar’s video may have an ethnographic focus, it is leavened by drama and humour. Rao’s large, painted visage looms over the hoardings that need to be taken down by a group of workers after the rally concludes. The process of deconstructing the hoarding proceeds in an unhurried, piecemeal fashion as the workers exchange rhythmic small talk and vie for the attention of the viewer (and the filmmaker). Rao’s larger-than-life image may have won him an important campaign of political recognition for himself and a new state too, but the workers in the film are yet to establish their own presence over the landscape. Badhwar’s observational camerawork does little more than frame these men as they approach him—wondering if the recording has begun—or shoot them against the dying light of the sky as they strip the temporary scaffoldings. Bereft of the energetic kitsch of campaign posters and the teeming crowds that populate such rallies, the site appears to be forlorn, as if something had ended, instead of the realisation of a new means towards greater political justice. The men who work on the site come to occupy the dim aftermath of a successful campaign, implying the disenchanting, anti-fairytale question: what happens after happily ever after?

Badhwar’s work has previously explored the radical legacy of the poet, singer and former Naxalite, Gaddar (Gummadi Vittal Rao). Gaddar’s revolutionary politics of self-recognition extended as a support for the foundation of the new state of Telangana that would realise the promise of fairer representation of those belonging to the lower castes in the public sphere. Even as he provided a wide template of grassroots legitimacy for the Telangana Movement, the formal political apparatus that came into power and appropriated the movement for its own relevance increasingly relegated the question of pointed social justice to the margins. Is it enough to gain a new cover of sovereign power when the vital spark that set off that sovereign demand in the first place gets diluted or formalised into abstract political performances of grievance? In the steady movements of the workers documented by Badhwar, one can sense the filmmaker’s intention to move beyond ironic representations of Indian political culture. Irony offers an easy pathway out of what appears to be a tragic incommensurability. The promise of lower caste recognition and the march of new democratic political formations appear to run closely but in parallel lines.

All images from Work Starts Now by Kush Badhwar. India, 2014. Images courtesy of the director.