Floating Imaginations: Afrah Shafiq’s Sultana’s Reality

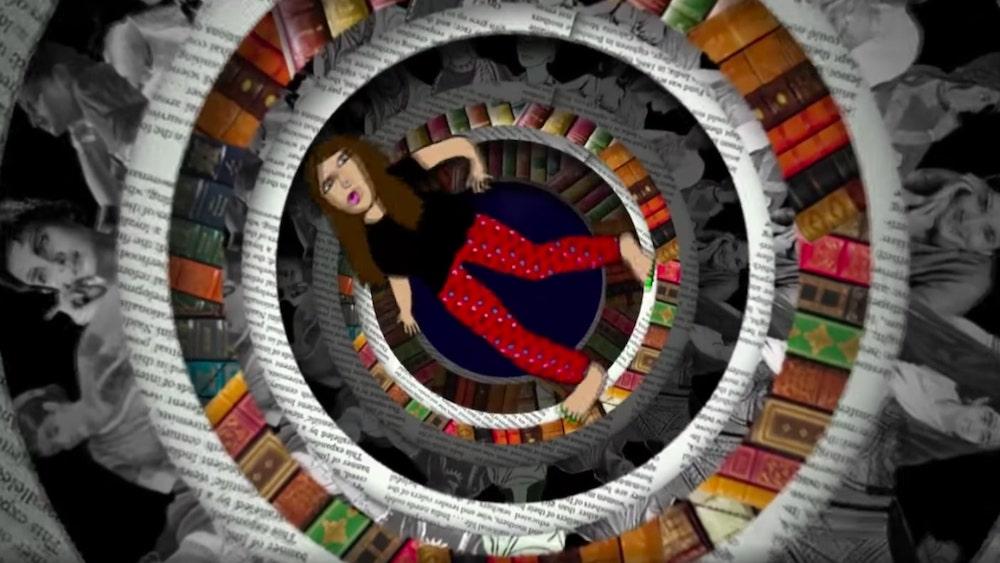

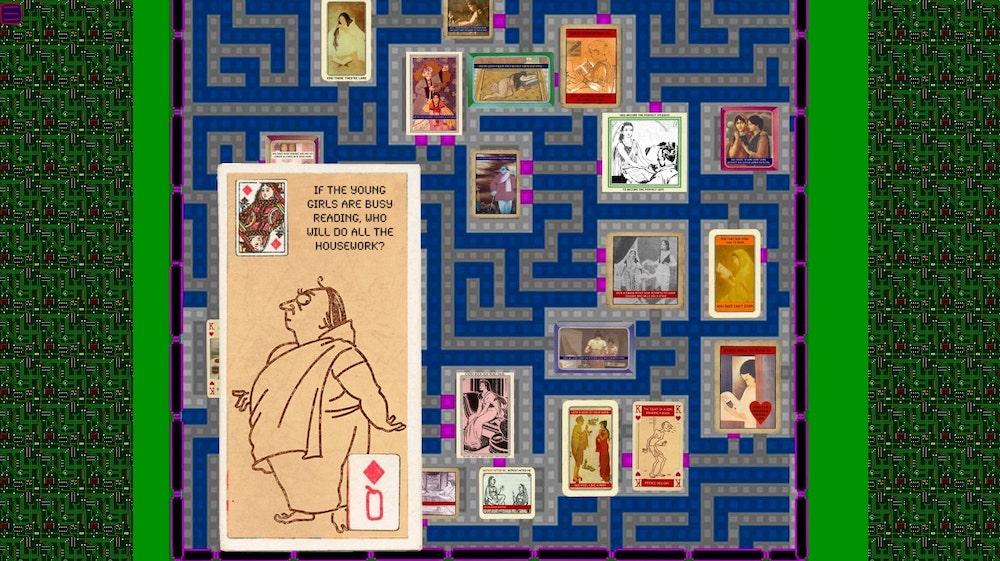

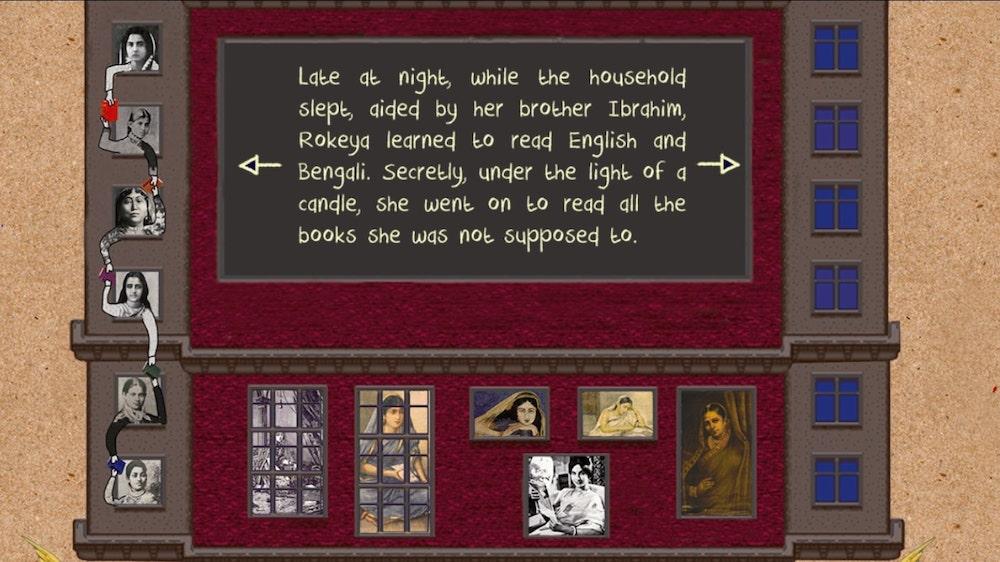

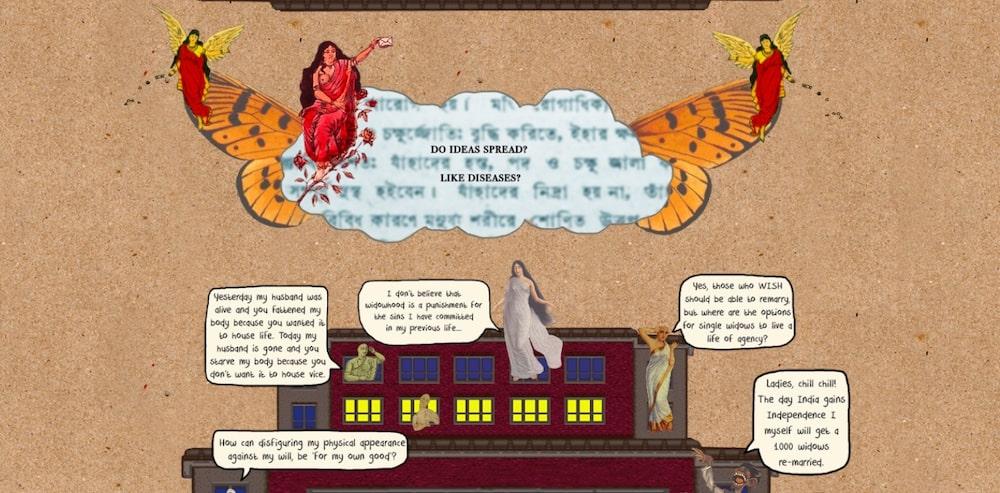

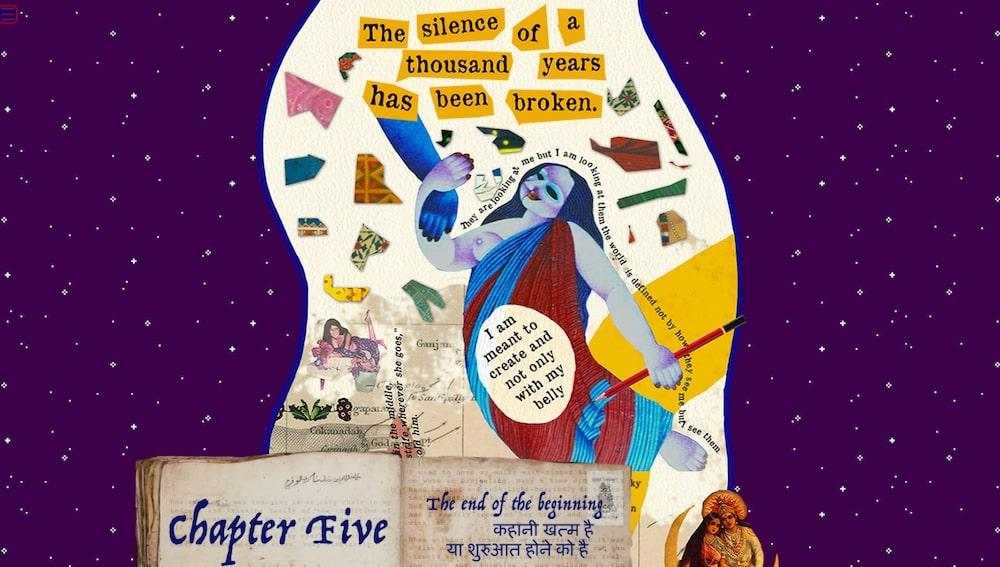

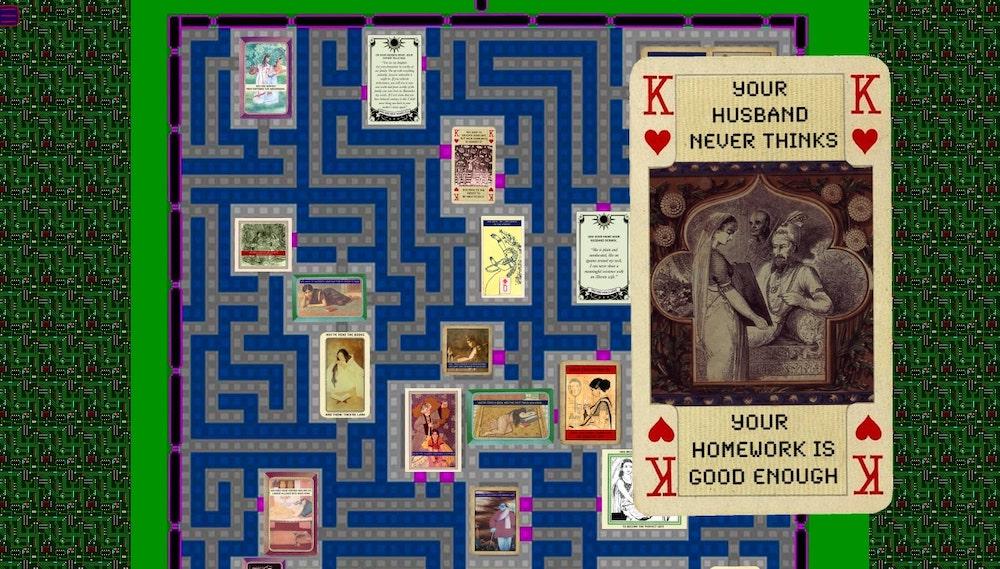

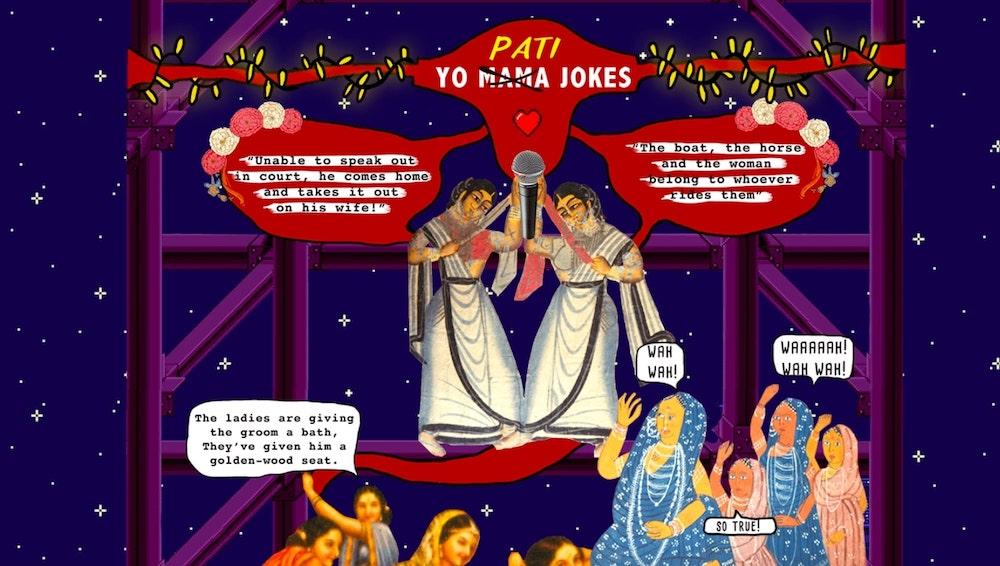

Sultana’s Reality (2017) is an interactive multimedia work that draws on artist and illustrator Afrah Shafiq’s time spent in the archives at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta (CSSSC) as part of a fellowship with the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA). Drawing its title from Sultana’s Dream (1905), a science-fiction short story of feminist utopia by Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossein, the work circulates primarily as a website with striking animations and playful virtual tunnels. It is an artis t’s interpretation of, and intervention in, the stories of women in the archive. Shafiq’s approach to the material in the collection was in part driven by research and her background in literature but largely a speculative exercise on the inner lives of different women and how they related to and navigated education in pre-independent India, particularly as these experiences are not documented in conventional textual sources from the period. Foregrounding the creative potential of reverie, the artist mobilises a variety of popular visual codes such as tarot, cinema posters and early Microsoft interfaces, among others, to draw viewers into the intricate and complex experiences of women in the region’s recent history.

In this conversation with Samira Bose, Shafiq elaborates on her purpose and process behind the project.

Samira Bose (SB): What was your approach when you entered the archive at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta (CSSSC)? What were you looking for, and what did you begin to notice?

Afrah Shafiq (AS): I went into the archive at the CSSSC through a fellowship supported by the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) in 2014-15. I had a particular idea, but what I ended up doing was quite different. What interested me was the range of material in the archive, including popular forms such as Bazaar Art or Kalighat paintings, calendar art and matchbox labels. The archive had early movie posters, photographs and illustrations and advertisements from magazines and books. It also had paintings, lithographs, audiographs and prints. Considering the range of material, I thought it would be interesting to look at one particular aspect and how it manifests through the many approaches or imaginations of the visual.

From the onset I was interested in looking at not only how women were represented in art but also in the ideas of cheek and impudence. I was then reading The History of Doing: An Illustrated Account of Movements for Women’s Rights and Feminism in India, 1800-1990 by Radha Kumar, and remember the small, everyday acts of protest she wrote about. In the late nineteenth century, Anandibai Joshi and Kashibai Kanitkar decided to wear shoes and carry umbrellas and walk on the streets—not a big deal for us today but at that point was a way of claiming superiority, and people threw stones at them. Savitribai Phule had garbage and sewage water thrown at her while on her way to teach, and so she started carrying an extra sari to change into once she reached school. These are examples of women’s resistances, and within them there’s cheek, and I went into the archive looking for this element of cheek.

During the selection process for the fellowship, I was asked: "What is cheek? What does it look like? What if it’s not cheek?” As I went deeper into the archive, a lot of my ideas changed. I was working with an archive for the first time and its sheer scale felt overwhelming. The material was digitised but not on an online interface or a digital archive, so I had to access images on hard drives via accession numbers. What I was looking for was actually outside the organising logic. I decided to look at all the images in CSSSC’s archive and sub-archive. I didn't go through maps or documentation of the city as they didn’t feature as many women. However, the CSSSC’s archivist Kamalika Mukherjee was of immense help and knew the material so well.

Keeping my idea of the element of cheek aside, I simply segregated the material according to whether it featured women or not. I began to notice different themes emerging from these images; for example, there’s a woman sitting by the window with a blank expression, looking outside, and I made a folder titled “Blankly Staring Out of a Window”. There were sets of images of women in groups, simply having a good time—lying down, heads in each other’s laps, combing each other’s hair—and this kind of intimacy among women became another image. I began to read the visuals almost through modern-day hashtags, such as women with books, but they weren’t homogenous—some were studying willingly, some were disinterested. I started interrogating the story of women and books further. One of the ways to go about it was to study the history of women’s education in India and the movements around it.

The connections I was trying to make were not strictly scholarly, and I had the liberty of not being burdened by that. I looked at the spirit in those images and saw how they could be reframed in the story I was telling.

SB: I am very drawn to your creative metadata methods, and it would be interesting to see how that would translate in an archivist’s spreadsheet. The stories you tell are through animated videos, graphics, GIFs, comics, collages and other digital art forms made by collating, re-mixing, re-interpreting and re-imagining traditional visual imaginations of the female form. What was the purpose behind your digital renditions of the materials?

AS: Looking through the images of women in the archive, I realised that very few were made by women themselves. Who was creating these imaginations and what were the lives of those actually residing within those images? I felt the women were trapped in the images. There’s a very specific set of images from which this impulse emerged—some of the earliest studio photographs of women from elite, aristocratic Bengali families, taken to be circulated for prospective wedding matches.

I noticed their expressions weren’t demure at all; they looked at the camera blankly, almost poker-faced. I remember reading an essay from Recasting Women: Essays in Colonial History (1989) wherein a woman recounted how she did not want her photograph taken as she wasn’t interested in marriage. The only possible form of protest then was to deliberately make horrible facial expressions and hope that she wouldn’t be selected. It made me think about the autonomy the women in the photographs were performing, and I animated a lot of those. There are several instances based on my readings of women’s own testimonies in their writings such as biographies, diaries and letters.

My initial plan was to make a short, non-fiction film but as I mapped my findings in the archive, I realised there were many simultaneous threads that were important to consider at the same time, which were not linear. One can’t generalise something as broad as “women in books”. I wanted to make a work where one can go back and forth. It took a lot of trial and error to develop. For example, in Sultana’s story, there’s a series of tarot-like cards that could take you in different directions, metaphorically, based on the cards you were dealt. How does one allow for those stories to not be placed hierarchically but to be on the same plane? That’s partly why this form was chosen.

SB: An aspect that stood out for me is Sultana’s Post-Its and the hidden notes and asides that are part of the broader narratives and images in your work. I suppose this captures the smaller stories one encounters in an archive really well, and the digital is able to render these well. I am curious about how you work between representing the archival materials, speculating on the images and creating fictional narratives. Are there certain responsibilities you feel towards “originary” archival material?

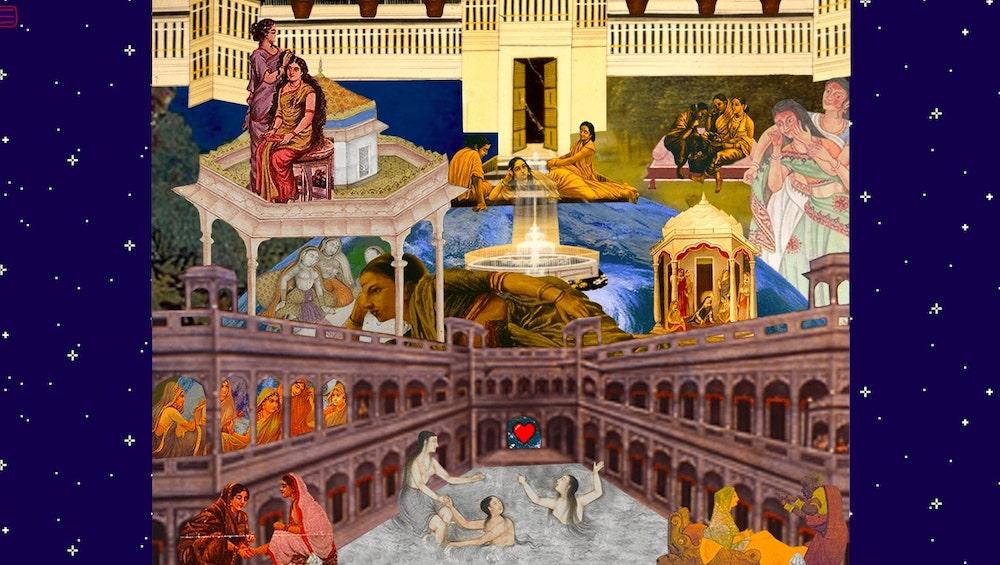

AS: I definitely do not feel completely free. It would be unfair to the context and those represented in the material themselves but I don’t have the same pressures a scholar might have. I still edit documentaries, and often ask myself the same questions while doing so. As an editor who receives footage, there is the potential to place it elsewhere to create another meaning. While that can be a craft, it can also be highly manipulative, boiling down to questions of ethics and intent, and the same is true for archival material. I don’t feel burdened by the exact linkages of images; in fact, I respect the spirit of the image. Perhaps an example will illustrate this better. The series of photographs of courtesans from Piramal’s collection at the CSSSC showcase women performers of various art forms, with crowds of people watching from the courtyard. When I was on the andar-mahal sequence, reading about these all-women troupes and the kind of tracks they would perform, many genres and sub-genres emerged. I haven’t used the original photographs of the performers but ones of other women performers. I designed fictional album covers with additional details like labels with warnings for explicit content. It doesn’t make you think what the original looked like. It's contemporised and remixed, giving you an imagination of what could have been without actually tricking you that this is exactly what it’s like.

SB: Coming to my last question, which quotes something you had previously written, “Sultana’s Reality is perhaps an exercise in questioning history, not the history of the image, but the history that is constructed with the image”. What does this mean?

AS: This is related to my experiments with the images at the CSSSC archives. I was familiar with the texts through studying history and literature earlier but entering from the point of the image was new for me. The images in the archive—particularly the popular ones—are the kind that create deep impressions on one’s mind. One can see that in contemporary image-making, there are recurrent imaginations. These aren’t things that happen unintentionally; that's how images construct meaning-making and ideas in people’s minds. One could have perhaps looked at the works in the archive with a certain lens, such as focusing on Raja Ravi Varma’s lithographs and what the history of that image, the form, the technique and the person who gave visual imaginations to what gods and goddesses are supposed to look like and have that imprinted in our minds. That's one kind of history of the image but what if the history that's constructed of the image is more abstract? One makes instant associations because one is constantly looking at that image of factoring being repeated, and then breaks that apart. This was the exercise I was trying to do with my interruption in the archive.

To read more about the CSSSC archives, please click here.