Memory, Material and the Spectral: In Conversation with Sumakshi Singh

Afterlife. Installation view. (Sumakshi Singh. 2022. Asia Pacific Triennale, Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia.)

Working with and against perspective, depth and illusion, artist Sumakshi Singh’s installations are extensions of queries around material flexibility. Taking an interest in the relationship between figure and ground, the recipient of the Emami Art Asia Arts Future Award 2022 explores how we progressively learn to classify visual attention, and how these processes can be altered to view the familiar differently. Meditative and durational, Singh’s works explore the idea of scale as both life-size renditions and microscopic interiorities. Crafting immersive environments that engulf their existing architectonics, her practice accords the viewer the role of a participant, one that works in tandem with the artist to materialise the work. Singh talks about her projects, processes and the impulse to interrogate the temporal fractures running through perceptual accuracies, thus creating conditions for disturbance, scars and fragile ontologies.

Garden Doors, 33 Link Road: Spectres of Home. Installation view, detail. (Sumakshi Singh. 2020. Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. Thread and steel frame.)

Najrin Islam (NI): The idea of “home”—and an accompanying sense of loss, transience and memory—is intimately tethered to your work. It has taken shape through projection mapping, virtual animation and drawings. What role would you say architectural residue plays in your practice?

Sumakshi Singh (SS): “Residue” and “residence” both come from similar source words that mean “to remain”. But they have different relationships to time and space—while “residence” is of the present, “residue” implies a layering of pasts. The residue is a small fragment of a space, and can become a portal to the whole, like a hologram, which ties up with my idea of “home”. Home has a form, function and an emotional resonance, all of which transform over time. What happens to form when it is done serving its function? My work explores these meanings, feelings and resonances that shape-shift with time.

In my recent work, the solid, sheltering surfaces of my now-unoccupied family home at 33 Link Road, New Delhi, turn into ethereal, ghost-like veils. Its architectural surfaces are rendered in delicate, white thread in life-size scale—hovering like a weightless labyrinth, and echoing an insubstantial landscape of memory. In my earlier body of illusion-based work, the image of the living room from this home skews, breaks apart and finally gets erased (like a mandala) as viewers walk in. In the animations, embroidered marks emerge stitch by stitch, as the needle appears to weave in and out of walls to create life-sized doors. These doors then hover for a moment before morphing and dissolving back into their original material (thread). So residue, transience, transition, memory and dissolution move through many bodies of work, using architecture to create a dialogue between materiality and immateriality.

Sight Specific. (Sumakshi Singh. 2007. Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, USA. Tinted aluminium foil on canvas.)

NI: In your illusion-based work, you orchestrate an interesting flattening of vision. Solid, three-dimensional forms perceptually liquidate into two-dimensional images, challenging the mechanics of everyday vision. Would you say that this additive exercise in meaning-making calls for an acute sense of artistic control?

SS: Around 2006, while in my studio, I noticed how my vision was flattening out the three-dimensional form of a stool into two-dimensional shapes. The stool would have to be drawn on any part of the background architecture (or objects the stool was covering) for me to see it this way. If I managed to freeze this map in space and shifted my head by even an inch, the image would break apart, turning my own perception from a minute ago abstract. I saw how unstable our perceptions are, and how contingent on where we are standing in space and time. This was the same year my grandfather passed away. Walking through the living room he had occupied, I was filled with a sense of the uncanny as these once-familiar objects seemed to have shifted meaning. I knew so intimately what they were, yet I was unable to perceive them the same way in the present moment. I was looking for the reassurance of fixity and familiarity, but was unable to find it. So my perspective-based work came out of trying to process this gap between perception and knowledge, transience and fixity, past and present.

In this body of work, I re-create a three-dimensional space by using the physical objects in the studio as surfaces for the cumulative image. From one vantage point, the illusion lines up, effectively obliterating the physical objects situated in the space. As we walk into the installation, our perceptions shift with each new location, adding and subtracting information that transforms or even nullifies our previous understanding of the space. Forms skew, lines fracture and a clash between the real and the virtual emerges. While we move through this disorienting world, we simultaneously see ourselves on screen where we are moving through an aligned illusion. We negotiate our existence in two spaces at the same moment in time, trying to see what the implications of a gesture or action in one space could have on the other. Walking through this work thus entails a continual navigation of these shifting landscapes.

The process fascinates me too. I often think I need to draw on a surface two inches away to line up my illusion, and it actually turns out to be twenty feet away! I am constantly mapping out a version of an image that does not correspond to where I am standing in space. It is like I am trying to create a reality that I cannot exist in, and I can only exist in its illusion.

Mapping the Memory Mandala. (Sumakshi Singh. 2008. Camargo Foundation, Cassis, France. Dry pastels on objects and architectural surfaces.)

NI: Your work with embroidery gravitates towards a relatively more permanent exercise in mark-making. Here, you also reference your relationship with your mother. How do you see the delicate entanglement of form and material with respect to filial connection?

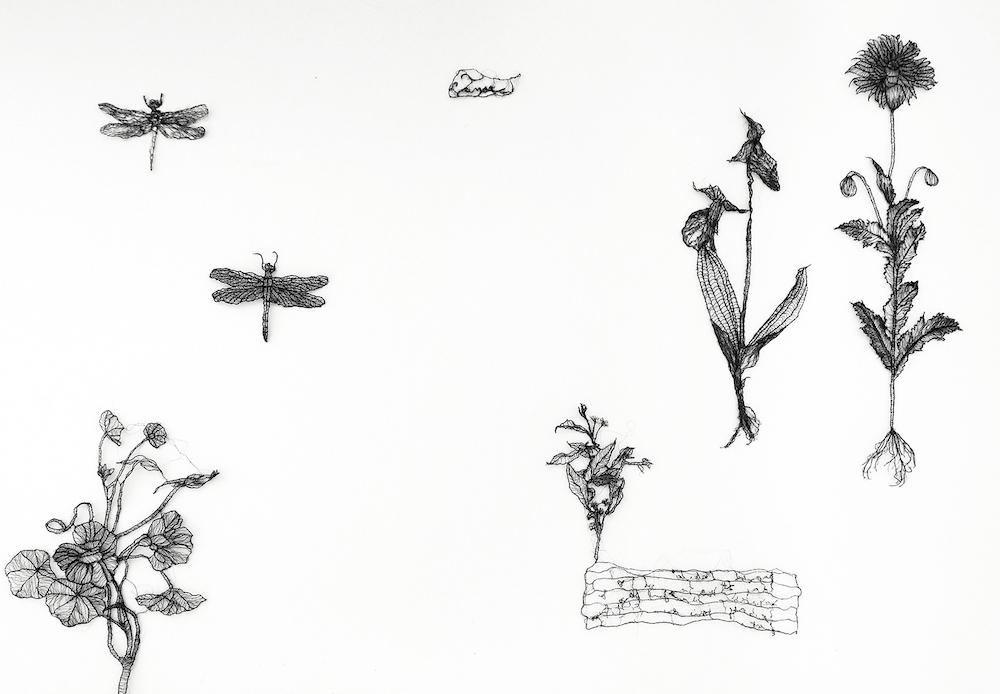

SS: My mother was an accomplished embroiderer and a landscape artist who created many incredible gardens. She passed away in 2013. As a way of feeling her presence, I began to trace out her handwritten letters addressed to me, and then embroidered her words on fabric. This was my way of “fixing” her words; in embroidery, the words are tethered to the ground fabric and cannot be easily erased like in a drawing. Ironically, when I was done with this, the words seemed to protest being tied down, as if unable to move or breathe. They seemed to want to be open, living things that I was trying to “fix,” and that was death. I started experimenting with various techniques until I finally embroidered her words on soluble fabric—this dissolved the ground away, leaving behind the levitating words. I then started to embroider the plants from her gardens (some of which she had pressed flat and sent to me in these letters). Soon, this skeletal archive of personal memory started to develop and the full-scale, thread gardens emerged out of this exercise.

What I love about this technique is that the support structure that the thread uses to build itself into a form is finally disposed of, and the embroidery (which was a surface embellishment) becomes the core structure, and the armature that holds itself.

Detail: table top. Tthread drawing. (Sumakshi Singh. 2016. In The Garden, solo exhibition, Exhibit 320, New Delhi.)

NI: Many of your bodies of work employ an immersive vocabulary. How is “experience” central to an understanding of your work?

SS: What I enjoy about the kinaesthetic experience (the way our body feels as it interacts with objects and spaces) is that it is very direct. It puts one at the heart of the experience without the need for much mental mediation. In immersive installations, the viewer is no longer a “viewer” seeing something from a distance, but now inhabits the artwork. The body receives the work and responds to it; does it feel welcome, overwhelmed, familiar, alienated or disoriented? Is it moving differently? Has the rhythm of walking or breathing started to shift? Is the peripheral vision engaged? Several subtle phenomenological clues add to the usual ways of decoding and processing artwork, and it’s only a natural extension of how we process information in everyday life.

Detail: thread and wire. (Sumakshi Singh. 2018. A Blueprint of Before and After, solo exhibition, Wilfrid Israel Museum of Asian Art and Studies, Israel.)

Blueprint, detail. (Sumakshi Singh. 2018. 58th October Salon/ Belgrade Biennale, Serbia. Thread and wire.)

All images courtesy of the artist.

To read more about the work of Sumakshi Singh, please click here.

To read more about the work of the honorees of the sixth edition of the Asia Arts Game Changer Awards India, please click here.