Acts of Tracing, Cutting, Isolating: On Nihaal Faizal’s Solo Exhibition ‘Special FX’

It is a discomfiting experience to watch media that characterised our childhoods, and to witness how it has “aged,” from lenses that are attuned to the mediatic environs of the present. Bengaluru-based artist Nihaal Faizal grew up in India in the 1990s, the decade following the moment of economic liberalisation in the country as the markets opened up in 1991. It was also a moment when a number of budding Indian studios began collaborating with agencies overseas to produce computer-generated visual effects, which started pervading television series as much as mega film productions. As part of his practice, Faizal is interested in the media sensorium and documents of that period. He resurfaces and engages with these through conceptual gestures.

Having grown up in India during the 1990s, and as Faizal’s contemporary, I feel a particular affinity to his ideas. His work makes me deeply (re)consider this moment when the formations of what is “real” began to be shaken and deeply reconfigured. We were transitioning from the analog to the digital, with an accelerated experience of special effects primarily determined by market and state forces that recognised their seductive potency.

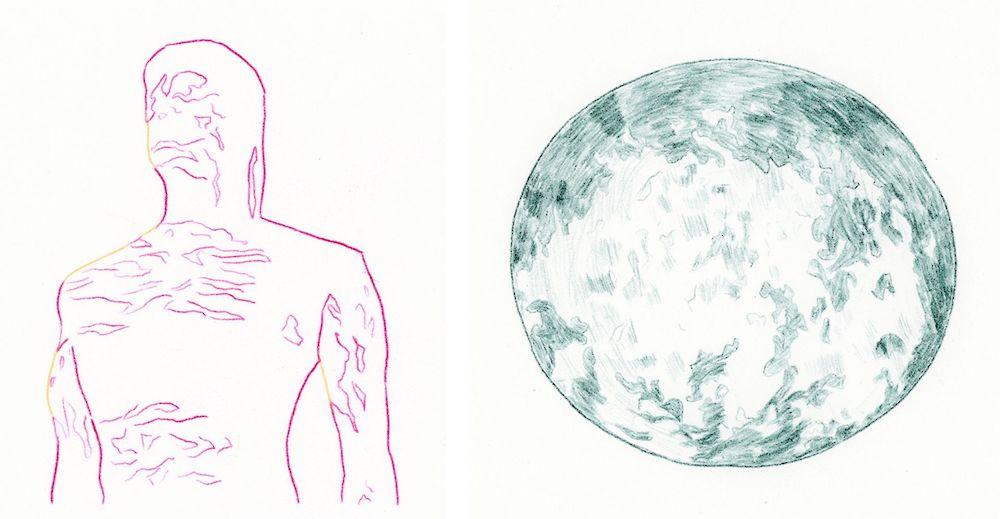

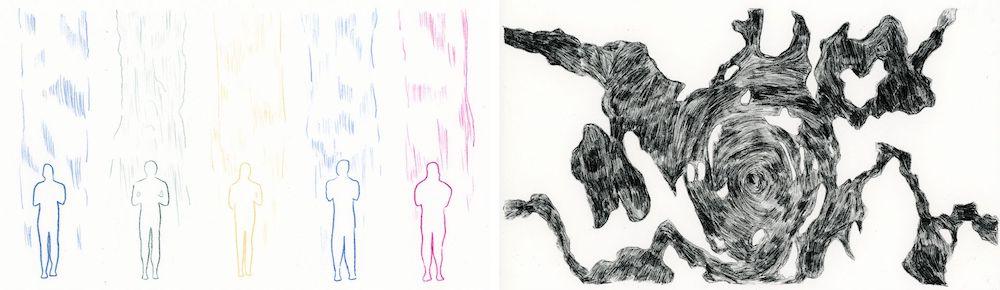

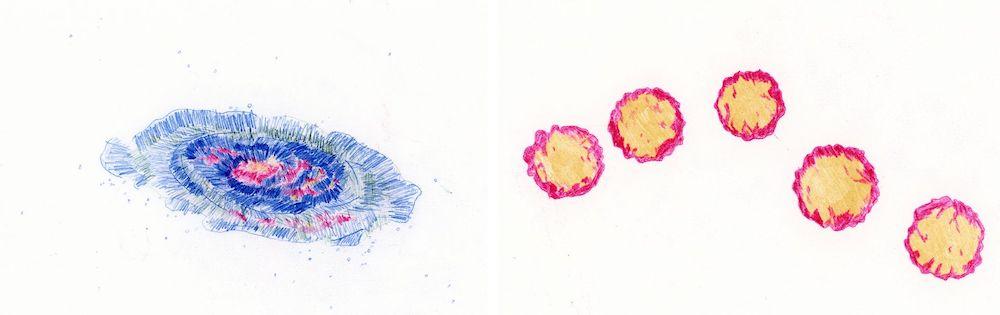

Shaktimaan SFX. (Nihaal Faizal. 2020-ongoing. Carbon transfer on paper.)

One of the bodies of work in Faizal’s recent solo exhibition, Special FX held at New Delhi’s Blueprint12, is Shaktimaan SFX (2020-ongoing). The work references and draws from the immensely popular Hindi-language superhero show, Shaktimaan, that began to air on television from 1997. With broad-chested muscularity, the protagonist in the show is seen to function in a universe premised on Hindu mythological references and whose powers were conspicuous visual “tricks” intended to enchant young audiences. In a series of drawings, Faizal works on stills from the show through simple yet precise gestures of tracing the special effects. He uses coloured carbon paper, thereby isolating the effects from the images, where we see only the animated graphics.

Shaktimaan SFX. (Nihaal Faizal. 2020-ongoing. Carbon transfer on paper.)

Underlying this work is another concern of Faizal’s which revolves around the concepts of the copy and multiples. In a work from 2020 titled Carbon Copy, the artist highlights how the act of copying is “located between drawing and printing,” and how the selective pressure applied creates residue that then takes a life of its own. The drawings in Shaktiman SFX are displayed serially in the exhibition, close to one another, and have a pulsating quality to them. Another narrative emerges and a different sense of movement appears in the drawings. In an illuminating essay for the exhibition catalogue, New York-based curator Joey Lubitz writes, “Part of the economy of the special effect is the project of contemporaneity—cutting edge, state of the art, a certain sublime potential of the artifice—all of which eventually wears off.” Personally, I find that Faizal’s playful process emphasises the visual “expiration” (Lubitz) of such effects and yet puts forth possibilities of unexpected afterlives.

Installation shots from the exhibition held at Blueprint12, New Delhi.

In one of our several fragmented conversations, Faizal and I discussed how mediated our memories from childhood from the 1990s are. They are often dependent on family photographs or are cinematically framed (probably semi-fictional), using bits from camcorder tapes and flashback conventions. If our sense of what is real was destroyed early on, how do we remember our own past?

In his other work at the exhibition, English Babu Desi Mem (Flashback Cut) (2021), Faizal plays 163 minutes of the eponymous 1996 film starring Shah Rukh Khan but redacts all sound and image except the opening credits and the highly stylised black-and-white flashback scenes. The selection of the film itself is based on its flagrant copy (without any mentioned citation) of the 1960 Hollywood drama It Started in Naples and its irreverent disregard for originality, a common feature across the history of Hindi-language cinema in India. Faizal’s interest lies in the specific conventions of framing flashbacks, along with the cinematic effects used to distinguish memories and past timelines. The projection remains mostly blank in the exhibition. Tentative viewers meander in and out of the room until a musical tune pierces through the exhibition and everyone gathers for close monochromatic shots of Shah Rukh Khan.

- 5.jpg)

- 10.jpg)

Screengrabs from English Babu Desi Mem (Flashback Cut), 2021, Digital Video.

While Faizal works primarily with found documents, his third work in the exhibition is a document that was produced through a provocation by him. In 2021, Faizal filed an official Right to Information (RTI) request to the Indian Prime Minister’s office, requesting a list of all the works of art displayed at the residence of the Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Titled RTI/1242/2021-PMR (2021), it comprises a scanned and printed copy of the government office’s response with the list of the works. Faizal has not intervened or mediated this document in any way, and presented it as is.

RTIs entitle citizens to information from public authorities who are accountable to respond within a month’s time. Instantly, the peculiar array of art is amusing, ranging from brass statue goats and a Seiko quartz world timer clock to replicas of stupas and framed newspaper cuttings from The New York Times. On a closer look, the partially disclosed checklist (with several details unfulfilled) conjures a view of the residence and its intended “effects” on viewers, revealing a dispensation’s investment in generic religious and bucolic imagery. The document presented can also be downloaded from Faizal’s website and be replicated, with the artist’s premise that the RTI be regarded as an act of publishing.

Installation shot of RTI/1242/2021-PMR, 2021, Public Record Document.

After I saw the exhibition, I asked Faizal about his purposeful acts of isolating and cutting, where he “removes” images and presents selective hints and traces. He responded that something about working with the form of found documents leads a lot of his works to be “reductive,” in that by isolating he is also highlighting. He suggests that cinema and popular culture have far wider circuits. Art, on the other hand, is limited in what it can do, and he quotes American conceptual artist John Baldessari’s investment in the phrase that “the only point of art is to point at things.”

All images courtesy of the artist.

To read more about the work of Nihaal Faizal, please click here and here.