Attuning to Toxicity: Does the Blue Sky Lie?

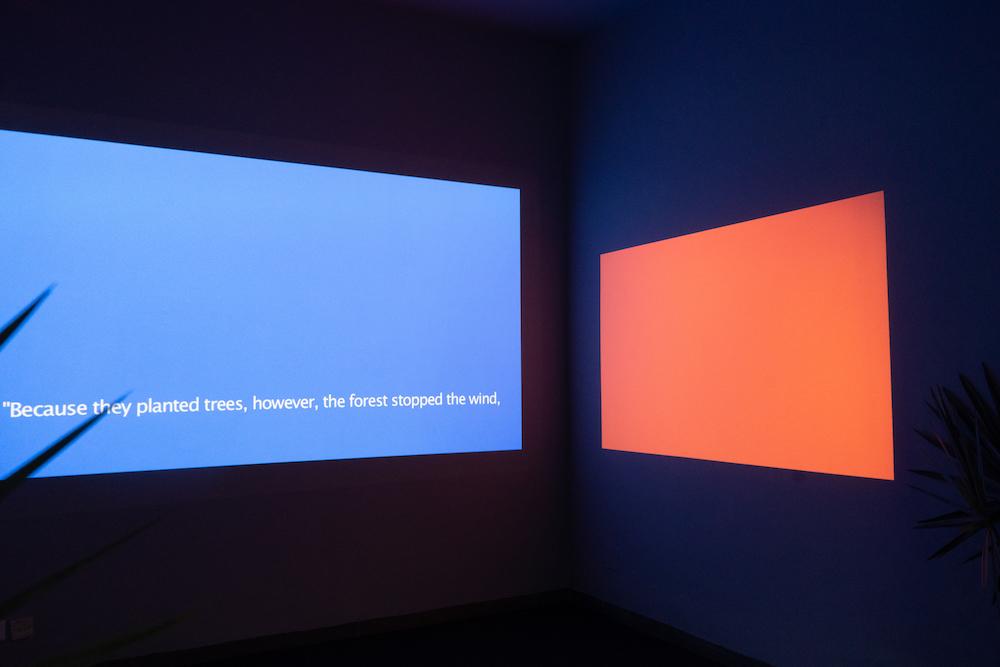

Installation image from Does the Blue Sky Lie? at Khoj Studios. (New Delhi, 2022.)

Less a pigment and more the result of light-refraction, blue is read as an indicator of “cleanliness” in the air—the indicator being the absence of particulate matter toxic to the system. The air just above the ground—the troposphere—is what we breathe and share with other in/animate beings. A space of habitation and routines, this realm of air is also one where the differences of environmental justice are most visible. The projects mounted by artists at the exhibition, Does the Blue Sky Lie? responds to the prompt of pollution, toxicity and the effects of extractive infrastructures amid the climate crisis through “embodied testimonies.” Deterrestrialising anthropogenic modes of thinking, the exhibition traverses a range of speculative attention to the air—through the meteorological, the socio-political and the affective.

Installation view of Often People Ask How Birds Are Affected by the Air. (Hanna Husberg. 2017. Audiovisual Installation, 25 min.)

The exhibition confirms the bleakness of the future while attempting to use the conditions that have generated the present to map out realignments in both the personal and the public realms. Hanna Husberg’s audiovisual installation, “Often People Ask How Birds Are Affected by the Air,” walks the viewer/listener through a plethora of testimonies from China, where air pollution has given rise to “wumai”—a health-threatening smog. It is mentioned that the word “smog” did not exist in the Chinese vocabulary and came into existence only after it was introduced by English author Charles Dickens in his literature and has been associated with Chinese air ever since. The knowledge has resulted in an increased datafication of the air, where the barometer of toxicity in the form of numbers becomes abstract in one’s understanding of its material imaginary. Somebody in the video mentions that they now look at the blueness of the sky as a “gift,” underscoring how the natural has become an exception and cause for celebration. Occupying the tracts through which we breathe, the pollutants in the air are microscopic entities, and are thus absent from daily regimes of visualisation. The increasing reliance on applications to predict air quality—and subsequently, monitor one’s own movements and anxiety—has resulted in tools such as air purifiers that alleviate the distress through compensatory promises of cleaner air. The project meanders through these public verbalisations, while air is established as a tangible habitus—one subject to a slow, incremental and invisible violence.

My house is ill at Khoj. (Architecture for Dialogue in collaboration with Salil Parekh. 2022. Site Specific Immersion.)

Salil Parekh in collaboration with the collective Architecture for Dialogue visualises this anxiety through the expanded residential space at Khoj, where he uses projections to create illusory vignettes of the exterior on solid surfaces, and installs light sensors to indicate contrasting qualities of air in adjacent closed spaces. Experienced through an immersive trajectory, “My house is ill” resulted from a series of experiments conducted by Parekh, and was premised as prompts around our motivations and ability to adapt to the climate crisis. The house comes alive in its illness, as the artist speculatively maps out how its interiors could evolve in response to poor air. It is designed for a chemically altered life—both of the concrete and its inhabitant(s). As a range of devices, practices and bodies come together to create an infrastructure that visibilises the air; numbers and codes present techno-scientific “solutions” to the crisis, reducing the climate issue to a perceptible (and manageable) scale. While we read the air’s undesirable excess through prosthetic extensions, can we imagine other porosities?

Installation view of An Elegy for Ecology at Khoj. (Sharbendu De. 2021. Translite Prints.)

Sharbendu De's immersive installation through a mis-en-scene of his photograph "Dzukou Valley, An Elegy for Ecology" explore how humans may navigate the world amidst rising temperatures and a possible lack of oxygen from global warming. Constituting an oxygen cylinder and a mask, the installation evokes the language of dystopia, as the apparatus awaits its eventual occupant. Staged in interior spaces imbued with the natural as well as the plastic, the images foreground the artist's vision of such a future—enveloped in a blue of, not the sky, but a disrupted green.

The Aerosol Chronicles Capture Omlojan. (Abhishek Hazra. 2020-21. Film in seven chapters)

As we engage with speculations around planetary futures, Abhishek Hazra reimagines the past of the planet. Unsettling the guarantee that the earth was always oxygenated, Hazra imagines an “oxygenation event” in deep time that purportedly resulted in its occurrence, presence, and subsequent use; thus establishing an alternative perception of air. “The Aerosol Chronicles Capture Omlojan,” divided into audiovisual narrations across seven episodes, uses a fictional figure as an anchor for para-historical speculations about archives of the air that include the anaerobic, the insurgent and all such “aberrant” agents left outside the ambit of apocalypse escape plans. The material, social and political assemblages that constitute air are rearticulated with and despite the methodological challenge of “invisible” infrastructures. Instead of studying its visible ruptures, Hazra performs a systemic inversion, focusing on the blind spots in histories and policies. Speculation is thus used as a strategy to explore a possibility in retrospect.

Safarnama by Saraab (Omer Wasim and Shahana Rajani. 2020. Sound Installation, 23 min 20 sec. Music played by Taj Mohammad and Abdul Hameed Baloch. Wall Illustration at Khoj Studios by Mohd. Intiyaz)

“Safarnama” by Saraab (constituting Omer Wasim and Shahana Rajani) uses the ephemeral entity of the jinn—made of air and fire—to disrupt colonial practices in seeing and knowing, and to reconfigure experiential modes. Mapping the extractive infrastructures of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor through the journey of a jinn across said landscape (borrowing the word “safarnama” from Islamic travel literature), the collective mounts a challenge to a state venture in erasure. Traversing across the sacred, the human and the ecological, the jinn functions outside the realm of official narratives, and occupies a liminal space of habitation. According to Islamic theology, the jinn emerges from the invisible (or “ghaib”) realm, which constitutes poetic knowledge, healing practices and mystical experiences entangled with the environment. The installation consists of continuous scribbles on the walls of the concrete enclosure, which register a landscape in cumulative vision—perhaps as ephemeral impressions of the jinns’ journeys beyond state topographies. Shape-shifting and refusing surveillance, the jinns are hauntings from an older world that would persist into the future. The narration equates such persistence to the desert-scape (that could potentially result from said project), which is yielded as a map only through its absences.

In another room is displayed Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra’s book and project, “Weeping Farm,” which emerged from observations around the agrarian crisis in India, including the conditions of food insecurity, privatisation and perpetual indebtedness. Specifically, they follow a group of women in the agrarian community, and the complications that issue from the double bind of class (intertwined with caste) and gender. The project includes “2030 Net Zero,” a card game that draws from Thukral and Tagra’s background in typography and printing to explore the amount of greenhouse gases that are released into the atmosphere each year, aiming to reduce it to “net zero” by 2030. Designed as a didactic game, Thukral and Tagra take the route of art pedagogy to disseminate said concerns to a larger mass otherwise placed at a distance from the crisis. However, one wonders if the practice of codification as an avant-garde gambit is an ethically appropriate means of initiation to the issue? A game is activated through intention to immerse, the choice resting with the player. This challenges the premise of shared authorship, as the content and subject of the game inhabit a simultaneous, albeit parallel, space of precarity that is determined by a macro-sport of exploitation by institutional agents of power.

Silence. Negotiation is on. (Pradip Saha. 2022. Audiovisual Installation.)

Pradip Saha’s installation “Silence. Negotiation is on.,” fixates on the overwhelming sense of effort produced through the number of international summits that have taken place to pledge to mitigate climate change. Details about the cities and years in which the twenty-six Climate Conference of the Parties have taken place appear on a screen in tandem, marking a long and failed attempt at tackling the problem. The failure has been attributed to market forces that determine changes over and above concerns for what may be beneficial to the ecosystem, resulting in business stalling any progress in the direction. This failure has been simultaneous to the durational accretion of carbon emissions in the atmosphere; temperatures kept rising as each capitalist venture got green-lit. This points to an exercise in the visualisation—not solution—of a problem that only serves to elongate it through strategic delays. As much as they are premised on the pressing need to take action, the summits function and persist through the lack of this urgency.

The projects as part of Does the Blue Sky Lie? set up a vision of the present where air is visible, toxic and alert to provocations. The trans-boundary trajectories of toxic matter point to a universal state of depletion and the strategic accretion of industrial matter reveals regional prejudice from capital accumulations. While the distinctions between local and foreign air, and us/them are reinforced against this knowledge, diverse sensitivities continue to adapt to toxicity through embodied encounters with data and other intensities. The only time we saw a clear, “blue” sky in Delhi was when the economy came to a halt during the Covid-induced lockdown in 2020, which necessitated an impractical pause in the production of food and energy; such a blue is not sustainable. Could blue exist in an infrastructure of transition? Could it persist as a space of cohabitation with urban ecologies that still extract? One looks back at the body for an answer…

All images courtesy of Khoj International Artists' Association.