Looking To Intervene: Formulating the Activist Documentary in A Bid for Bengal

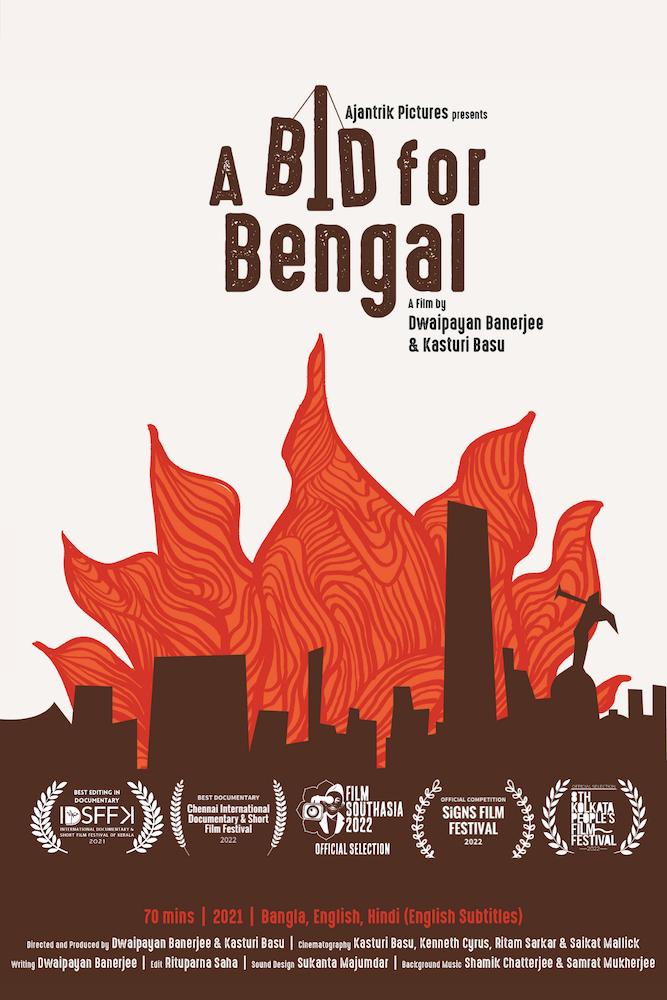

A poster of A Bid for Bengal (2021), directed by Kasturi Basu and Dwaipayan Banerjee.

Kasturi Basu and Dwaipayan Banerjee’s documentary feature A Bid for Bengal (2021) presents a narrative of the rapid advancement of India’s right-wing, Bharatiya Janata Party-led government towards transforming the cultural and electoral politics of power from the perspective of their activist filmmaking practice in Kolkata and West Bengal at large. Basu and Banerjee define themselves as “activists in a film collective” (known as the independently organised People’s Film Collective), rejecting any interest in non-partisan, “objective” reporting of national events. Documentary cinema’s tools of realistic observation are effectively appropriated by their film practice into a holistic assault against the consensus-making machine of mainstream media in India today.

The duo started out as festival programmers, running the increasingly popular Kolkata People’s Film Festival, one of the few film festivals in India that takes political opposition to right-wing supremacy as its central agenda. Over the years, specific themes have been tackled with their choice of films and filmmakers—ones that challenge hegemonic ideas about caste, sexual violence, the role of religion in national life, the extractive undertow that discourses of development inevitably carry in their wake, and recognising the broad, cultural world of the secular Left and their gradual decline over the last few decades. A Bid for Bengal is their second feature-film after SD: Saroj Dutta and His Times (2018)—Basu co-directed this with social activist and freelance journalist Mitali Biswas—which offered a glimpse into the troubled biography of Dutta, a former State Secretary of the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) in West Bengal, thought to have been assassinated by the police in 1971 for his role in the Naxalite Movement.

The film uses both fresh and archival footage interspersed with personal family histories.

Basu and Banerjee also co-edited a book titled Towards a People’s Cinema: Independent Documentary and its Audience in India (Three Essays Collective, 2018), which provided long-time attendees of the film festival with a programme of their intentions and methods. Explaining their approach, they wrote, then, in the introduction:

“From our experience, we have come to value the independent documentary as a potent site for seeding and nurturing counter-hegemonic ideas, narratives and languages that, given a chance at a back-and-forth communication with the wider audiences, can play a significant role in unsettling the dominant consensus—“common sense” in Gramscian terms—on matters of politics and philosophy, aesthetics and art. The documentary filmmaker then transcends her first role of a sensitive observer bearing witness to testimonies of injustice; as she also consciously intervenes with her films, by opening up questions to the wider society and listening to questions asked of her.”

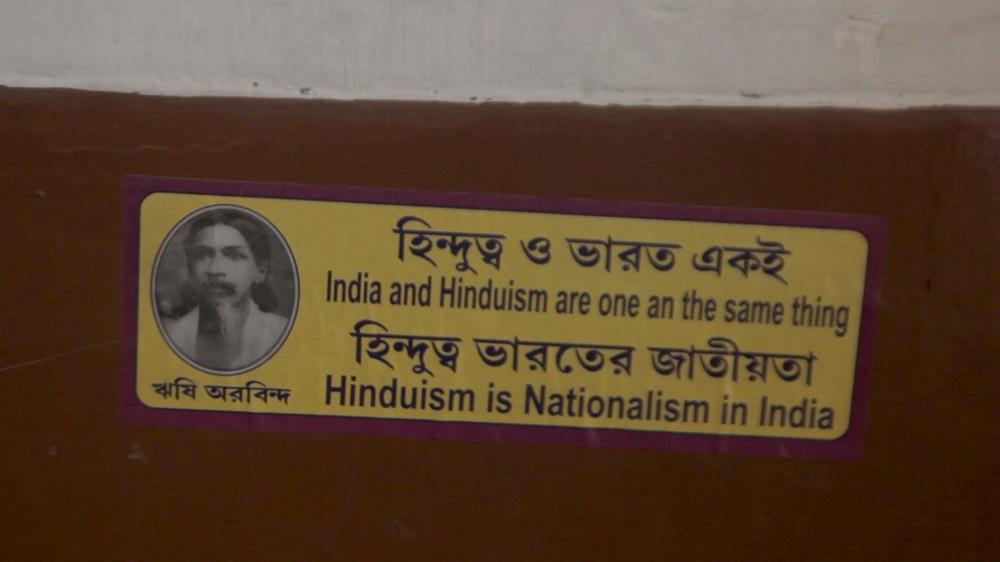

The film visits cow-protection committees and Ram Navmi processions, bringing to light the underbelly of the Hindu nationalist propaganda in West Bengal in the time span of the national elections of 2019 and the State Assembly elections of 2021.

In A Bid for Bengal, modes of observation are historicised. Acts of filming are shared and collaboratively stitched together from videos shot on professional or mobile phone cameras by other activists and filmmakers. Furthermore, archival images from British and European documentaries from the past are also used to demonstrate threads of continuity. The catholicity of the final film is deliberately ranged against the homogenising assault of the much better organised (and better funded) forces of Hindutva, whose activities in image and disinformation production we see briefly in interviews with BJP IT cell members and gau rakshak (cow-protection) committees tasked to repeat the central tenets of the ruling party’s cultural programme of self-victimisation. Collaboration, for Basu and Banerjee, becomes an ethical and human imperative that is woven into the structure of the narrative and its making.

The film brings to the fore the operation of the Hindu nationalist project in West Bengal.

By drawing on their own family narratives of activism and displacement, both Basu and Banerjee define themselves (and the substance of their “gaze”) as contingent, historical forces rather than individual, personality quirks. We learn that Banerjee’s father was critical of Mahatma Gandhi and belonged to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) until Gandhi’s assassination in 1948. Basu’s father was victimised by majoritarian violence in East Pakistan (set off by events in Kashmir), forcing him to migrate across the border to West Bengal. These narratives help recognise the latent power of the Hindu majoritarian sentiment in West Bengal that was only superficially buried after the death of Bharatiya Jana Sangh founder Shyama Prasad Mookherjee and, subsequently, during the years of Left rule in West Bengal. The filmmakers do not suggest any simple opposition between secularist (or even a clearly anti-capitalist) Left and religious Right, showing instead the easy conviviality that often existed between members across both these supposedly ideological extremes. A shared sliver of culture was always available to both, which could perhaps explain the easy movement of political leaders from the CPI(M) to the BJP before the major national and (West Bengal) state elections held in 2019 and 2021, respectively. These two elections, in fact, frame the narrative of the documentary.

If the film appears occasionally to have been ripped from the front pages of Facebook or Twitter over the last few years in Bengal, the heartburn it is likely to cause to some viewers is leavened by insight into a past that is free of myths of Bengali difference from a national mainstream that lies “elsewhere” (such as “North India”). It is also mindful of the specific historical tensions that Bengal and its shared border with Bangladesh have generated over the decades, culminating most recently into the formation of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). These events—and the historic agitations against these instruments of national exclusion—form a natural part of their narrative too.

The filmmakers not only adopt a politics of the resistant or rebellious image, but set out to challenge the electoral behemoth that set upon West Bengal in 2020 with action on the ground. Local activist collectives were formed (“Humans of Patuli”) and poster campaigns, titled #NoVoteToBJP, were aimed at restricting the groundswell of support that the BJP had already started to generate. This puts their documentary practice beyond the usual modes of visual critique, and by supplementing a cinema verite style with patterns of actionable intention, they manage to produce sentiments and structures for a more provisionally equal society to come. Stemming the tide or damming a wave is the immediate objective of the filmmakers; and this requires a re-consideration of the values of tactical, instinctive acts of filming and documenting, appropriating so-called “poor” images and creating a coherent thread of analysis out of such momentary visuals. In their effort towards suggesting the form that besieged media should adopt in the face of our modern crises, generated by an increasing stranglehold over the technologies of image dissemination and saturation, A Bid for Bengal successfully manages to marry its historical lessons with affective and sentimental protests against the ghost that haunts its own body.

Several poster campaigns, titled #NoVoteToBJP, were aimed at restricting the support the BJP had already garnered in West Bengal in 2020.

All stills from A Bid for Bengal. (Kasturi Basu and Dwaipayan Banerjee. India. 2021. 70 minutes.) Images courtesy of the artists.