Archiving the Photo Studio: Recall and Remembrance in Paper Envelopes

Passport-sized photographs have warranted inquiry for their stoic utilitarian malleability. Their travails between honorific and repressive portraiture (Sekula, 1986) have generated newer meanings along the way that keep evolving. In their foremost utility, passport-sized photographs ideally fit into the category of repressive portraiture due to their necessity and relatively easy access created by the state. However, this form often subverts the repressive and works itself into the honorific realm in South Asia, usually in the form of photographic portraits of remembrance among other categories.

Extensions of home in the field—two passport-sized photographs hang framed in a bedroom. (Kolkata, 2022.)

The physical journey of a photograph is deeply organismic as Roland Barthes puts it in Camera Lucida (1980), often akin to something that is alive. The paper envelopes used for passport-sized photographs, also colloquially known as the “passport photo” in India, are intrinsic to the life-cycle of these images. This image, however, is no longer the image used on one’s actual passport but just a set structure of framing and format for portraits primarily taken to fulfill a range of bureaucratic functions—the stamp-sized photo, or country-specific visa photographs. To get a passport photo “taken,” one still has to visit a photo studio. Over the years, however, newer technology like smartphones, portable printers and other forms of bureaucratic biometric imaging systems have taken a bulk of the image-making market from photo studios. This shift is synonymous with the idea of “digital India” fostered by the Central Government of India in order to create a digital ecosystem/ infrastructure of, and for the citizens. This particularly plays out in the creation of identification documents via photographic and biometric imaging, eventually encouraging citizens to store their documents in a digital locker, also launched by the Government of India. This ultimately calls for a paperless system of governance, creating seamless access between the deemed “citizen” and their government. The functioning of the Indian bureaucratic system, however, continues to depend heavily on paper and on “hard-copies” in which passport-sized photographs remain essential.

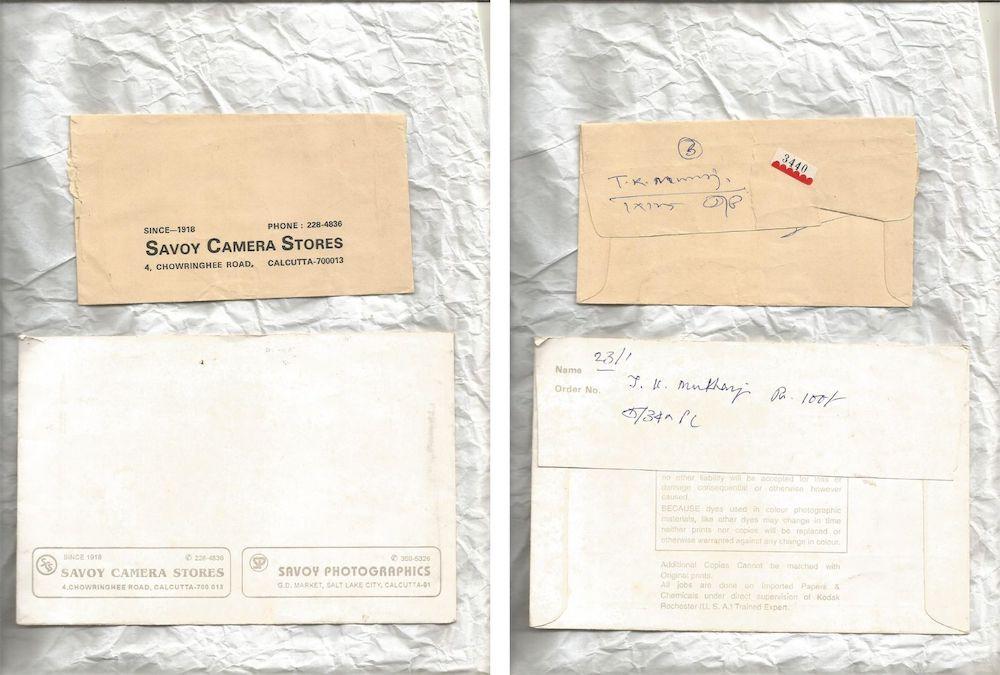

Envelopes from Savoy Camera Stores, 4 Chowringhee Road, Calcutta 700012.

Photo studios have made repeated appearances in research as spaces that facilitate intertwined opportunities of visibility, fantasy and mobility in post colonies. At a time when I was unable to access photo studios in-person due to the initial outbreak of COVID-19, I had to rethink how this space could be accessed in other ways for research. The material sediments of the photo studio that make its presence felt in an average domestic space in India made me look into the affectual potential of paper envelopes that hold passport photographs.

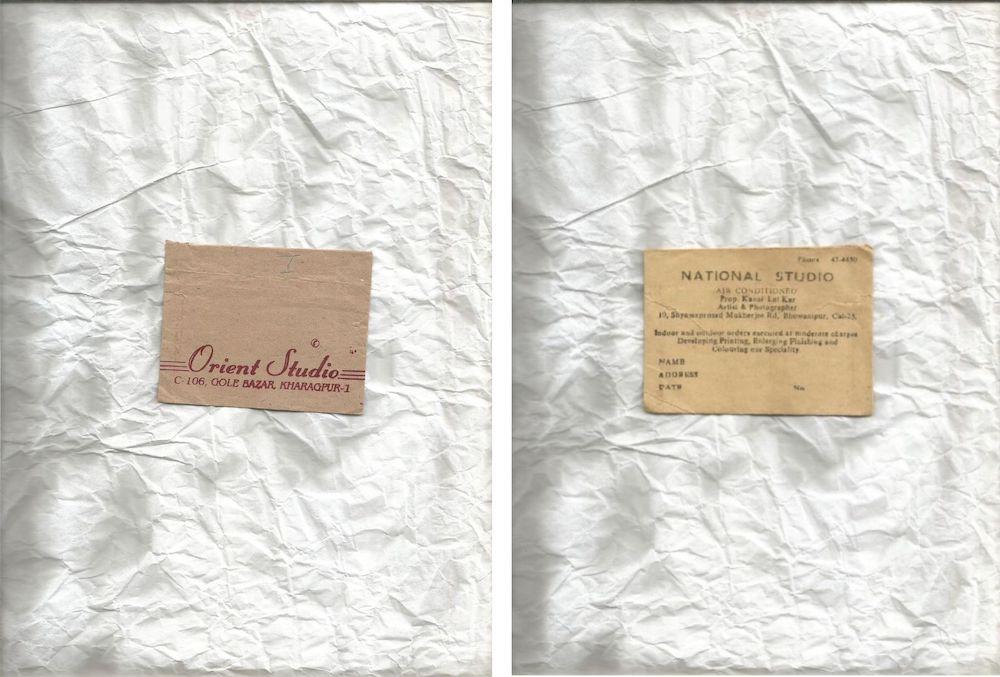

Yael Navaro-Yashin (2007), lecturer of social anthropology at Cambridge University, propounds that affectivity in the home in relation to bureaucracy lingers between the joint realms of governmental documents and paper photographs, and the envelopes contribute to these realms. This brief review is rooted in West Bengal; through the messaging and advertisement these spaces utilise on the little material that creates a form of potential recall to the studio. The images used to illustrate this article are from my family’s personal collection. If looked at closely, one can trace the movement of my family from one district and sometimes, a particular pin code, to another, based on where the photo studio was located. It is fairly simple for me to assume the locations where my family resided, because of their positioning as stable city-dwellers after they migrated from Barishal during the various phases of the Partition of Bengal.

Material sediments of the photo studio—Orient Studios and National Studio.

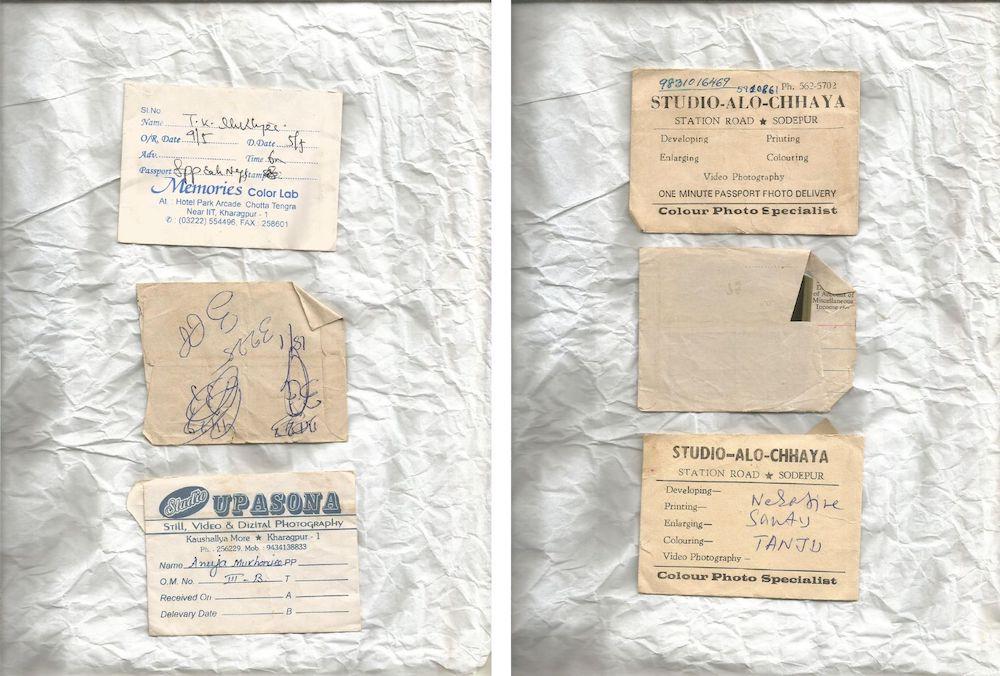

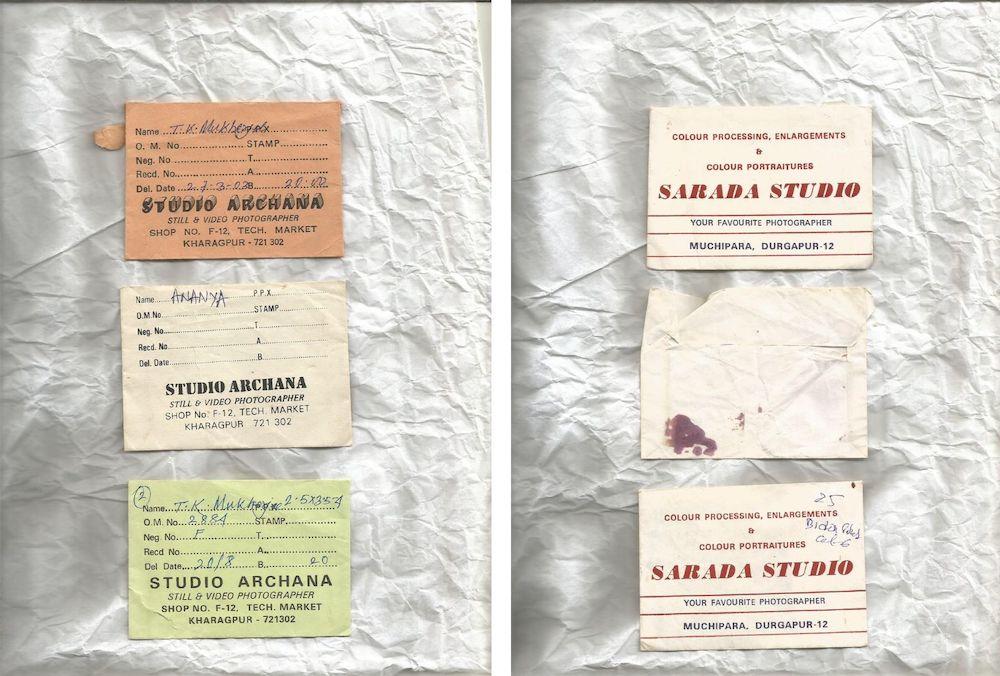

The envelopes create a mnemonic for the photo studios, inevitably locating the spaces in which people were photographed. In the images that we see in this article, it creates inadvertent captions for my family members and their photographs, thus personalising the moments and spaces. Markings like coded numbers, date of making, date of receival and proof of payment along with other scribbles for when the envelope doubled as a notepad can also be seen as a significant part of its paper geography. The envelope is perhaps a form of an afterimage of the photo studio that, as Christopher Pinney (2013) iterates, is an “endlessly repeated space” but largely invisible in passport photos. The passport photo format’s need and validity has led to the erasure of space and time in the studio. The essence of this image lies in its workability; it works everywhere because it only represents the photographed. It could have been taken anywhere. The passport photos taken inside the studio work to erase all evidence of the studio’s location with the help of a solid-coloured background/backdrop. Had the studio been visible, it would be too distracting for passport photos to work in bureaucratic settings.

In his thesis on colonial studio backdrops, Arjun Appadurai (1997) speaks similarly of this form of representation. The erasure of the studio space speaks in the context of contrast. The subject of a photograph usually positions themselves against/in front of/ behind/around/ on/in and other variations of creating a conscious/subconscious difference with/from another. These photographic portraits, however, make the subject its own context against the background that remains piercingly silent. In such a context, the envelopes speak for the photo studio.

Envelopes and the accompanying artifacts from photo studios such as Memories Color Lab, Upasna and Studio Alo-Chhaya.

The passport photo makes it apparent that the studio space is positioned in such a way that even when the studio space is visible, it is not repeated. Artifacts like the paper envelopes—that usually have the name, contact number, date and location of the photo studio—make the particular studio visible and re-visitable to the customer. Sometimes they also have written on them an accession number, in case a customer wanted to avail repeat prints from the soft copy of the same photograph. At other times, it is simply a blank beige or white envelope with the photographic product inside it.

Envelopes from Studio Archana and Sarada Studio.

Passport-sized photographs have an inherent capacity to leak into spaces from where they might be expected. Due to their mobile size (4.5 x 3.5 cm) created for ease of access and distribution, they not only grant mobility to the person who is photographed through evidence-making but also their physical, material mobility within the domestic space. This also makes them easy to lose; they have a tendency to be found scattered inside drawers, old files as they leave their paper envelopes or even come off of documents that they were affixed on to. Paper envelopes are overlooked but integral to systems that hold essential photographic documents and their tributaries in place as they fray over time. They organise the organisms.

The photo studio is a standalone space that specialises in creating printed as well as digital photographs to serve a variety of purposes. These studios do deliver soft copies to their customers but it is in the hard copies of passport-sized photos for everyday bureaucracy that the studio gains its importance. The envelopes hold and store the hard copies and negatives that the studio produces for the customer. The studio, as a space that is integral to citizenship, practices on various levels, and remains a site of continuous reproduction of the self. The fact that the idea of the self does not simply have one but many referents lend it different kinds of opportunities to generate versions of citizens. Photo studio envelopes showcase a form of co-writing from both the customer and the studio photographer/administrator that falls in the overlapping space between bureaucratic writing in the heavily-studied arena of governmental files, forms and folders, as well as anecdotal, archival writing on photo albums and postcards that traces pictorial memory through added script.

All images courtesy of the author.

To read more about studio photography, please click here.