The Video Moment: Piracy and the Bombay Film Producer

Magnum Video, one of the major video distributors of Bombay cinema was officially established in 1987. There were some deliberate confusions over its proprietors and real owners. Nonetheless, Magnum finally went into filmmaking with Baap Numbri Beta Dus Numbri (Aziz Sejawal, 1990). In 1989, Chandra Mohan Devdas Rao of Magnum Video reported the details of a raid he had conducted at Mumbai’s Mahalakshmi temple premises. As quoted from an article published in an edition of TV and Video World from the same year: “The film Kasam Suhaag Ki was being duplicated…by one Pratap Sampat. Among the equipment confiscated by the police were a Sony colour TV, 25 National VCRs, 4 JVC VCRs, 28 pirated video cassettes of Kasam Suhaag Ki and one master copy, 9 B.P. video cassette, 36 pirated cassettes of different films, 1 remote control, 3 equalizers and one adaptor.”

An advertisement for Magnum Video Cassettes appears in TV & Video World, March 1989.

By the late 1980s, all that the video buccaneers needed was an unassuming location to perform the act of copying the film (a religious site, in this case), a handful of televisions, video recorders, equalisers, an adaptor and the master copy of the film to be duplicated. Incidentally, Magnum Video—the company that conducted the raid—belonged to the duo Hanif-Samir, who were earlier held for video piracy and gunrunning for Dawood Ibrahim, and later turned out to be the major accused in the 1993 serial bomb blasts in Bombay. The video moment in Bombay, simultaneously ephemeral and viral, was murky, with its key players constantly switching sides of the law, sometimes to provide a false front to the mafia in the film business, and sometimes by fully laundering their black money into legitimacy. If video piracy (and even legitimate video distribution later in the decade) had threatened box office earnings of movies, the proprietors of video labels still kept producing films because film business was the easiest to launder money in.

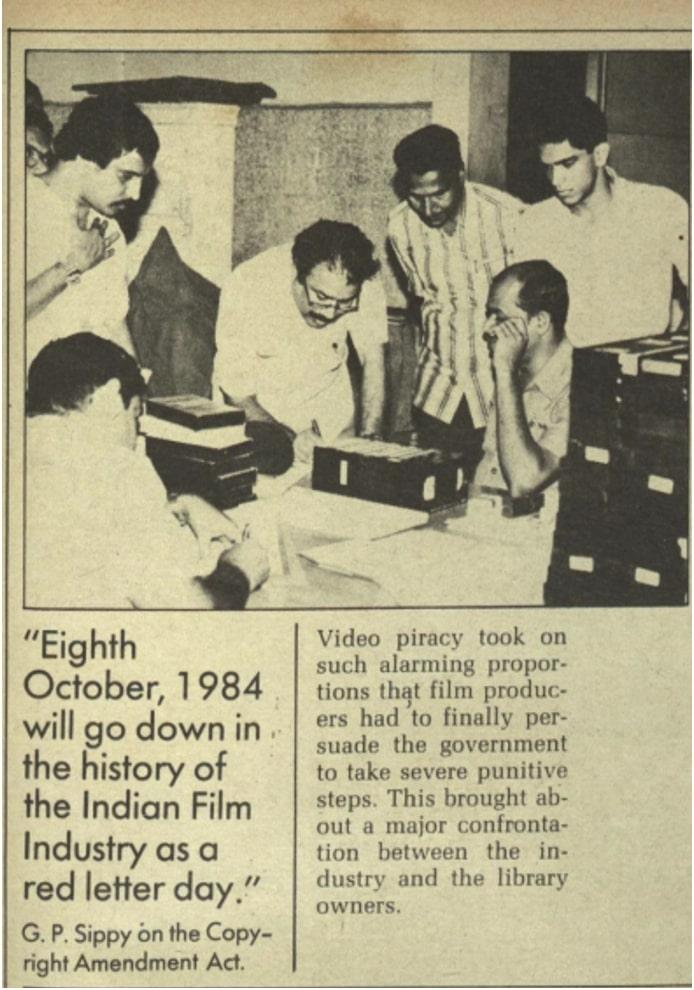

In the mid-1980s, when the piratical practices had wrecked the mainstream film market despite the institutionalisation of the Copyright (Amendment) Act in 1984, director Manmohan Desai was quoted to say: “Not even like cancer, it’s like AIDS. It cannot be cured […] piracy hasn’t been curbed any less in spite of the raids and it is getting increasingly difficult to pinpoint the source of illegal video cassettes.” To buttress the rights of filmmakers, the Indian Motion Picture Producers’ Association (IMPPA) instituted two bodies—Anti Video Piracy Organization (AVPO) and Film Producers’ Welfare Organization (FPWO) in 1984. But within a year, the movie moguls of Bombay entered into what was perhaps the biggest industrial controversy of the decade. It started with Ramraj Nahta, an editor of the trade journal Film Information, resigning from IMPPA’s presidentship on 9 May 1985, over a coup-de-tat against him launched by Vikas Mohan who headed AVPO. Nahta said in an interview with Filmfare: “All the anti-video raids were a big hoax. The man spearheading these raids was hand in glove with the video pirates and was conducting these raids to fill his own coffers. Even police officers told me of what was going on.”

An article on the Copyright (Amendment) Act 1984, as published in Filmfare, 16-31 January 1985.

The controversial anti-video vigilante, Vikas Mohan himself, created a furore over being roughed up by the “video king” Dhiraj Shah and reported the incident to a newspaper that headlined as: “Violence in video raid: Film man assaulted.” Nahta was succeeded by Prakash Mehra as the new president of IMPPA. This is when Chandra Mohan, then a crony of Nahta, reared his head as Vikas Mohan’s new rival. Thus began the game of mutual mudslinging, the rivals accusing each other of accepting hafta from the buccaneers against protection in the raids. Soon after, as published in an edition of Filmfare from 1985, anonymous letters were being sent to Mehra urging him to resign: “…As it is, you have brought enough disgrace to the industry by making IMPPA office a bar! […]”

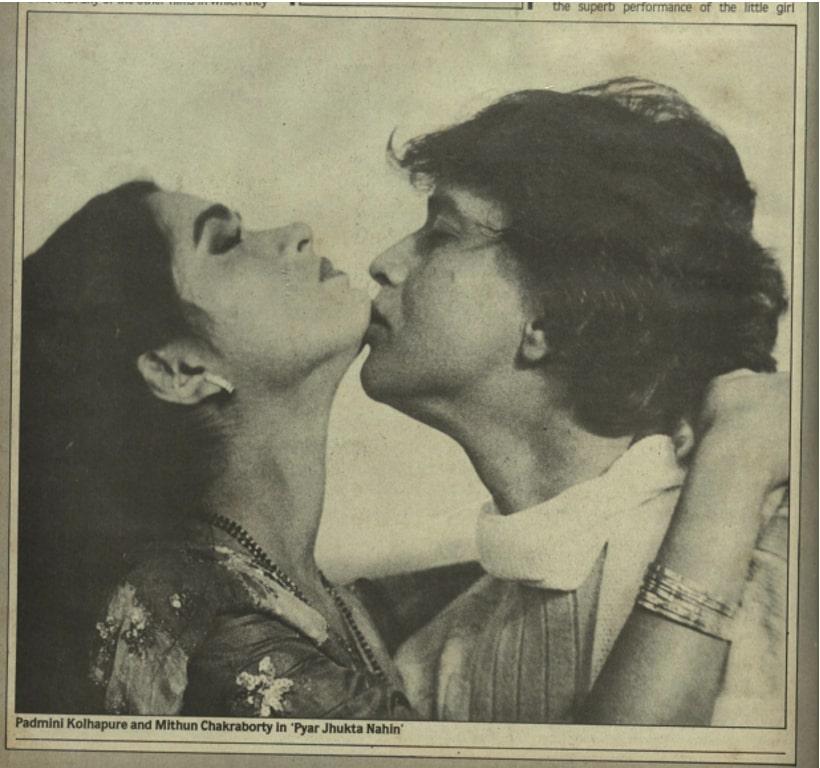

Actors Padmini Kolhapure and Mithun Chakraborty in Pyar Jhukta Nahin, as published in Filmfare, 16-31 July 1985. The film made its way back to theatres from the seedy video-cassette circuit.

Amid such openly sordid politics of the industry moguls and the reigning joke of the decade that filmmakers received telephone calls from video buccaneers offering to sell them their own movies that they had copied from video releases overseas, Pyar Jhukta Nahin (Vijay Sadanah, 1985) took the industry by surprise. Defying all precedents, the film broke box-office records. It won its way back from the seedy video circuit to the theatre, making a reverse journey from the villages and small towns to the big cities. It was a small-budget romance starring Mithun Chakraborty and Padmini Kolhapure, probably signed out of pity for the producer K.C. Bokadia. The film initially found no distributors, except in Bombay, where it was rumored that Bokadia himself released the film, possibly on video. Once the film had gathered a record audience overnight, theatre exhibitors wanted to buy back its rights. In an interview with Filmfare, a gallant Bokadia said: “Video cassettes are serving as a trailer for my film. After seeing it on video, people go and see the film in the theatres.” It took one film, Pyar Jhukta Nahin, to reinstate the industry’s faith in the video moment.

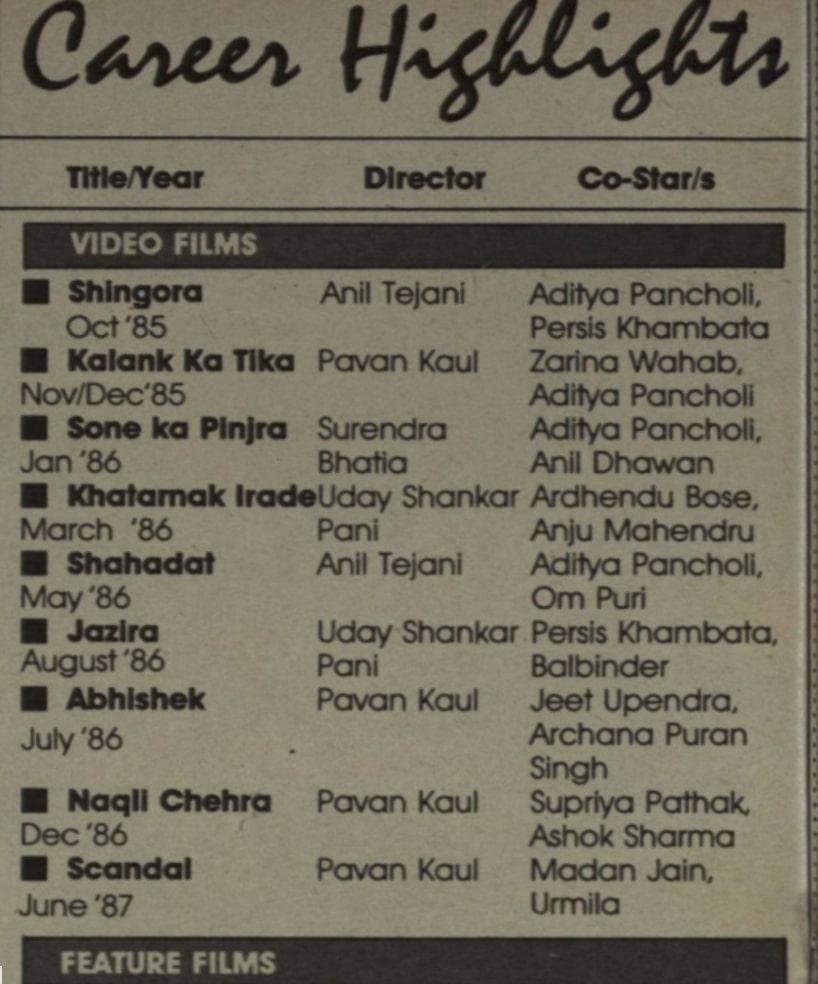

A list featuring the new crop of made-for-video films, as published in TV& Video World, January 1989.

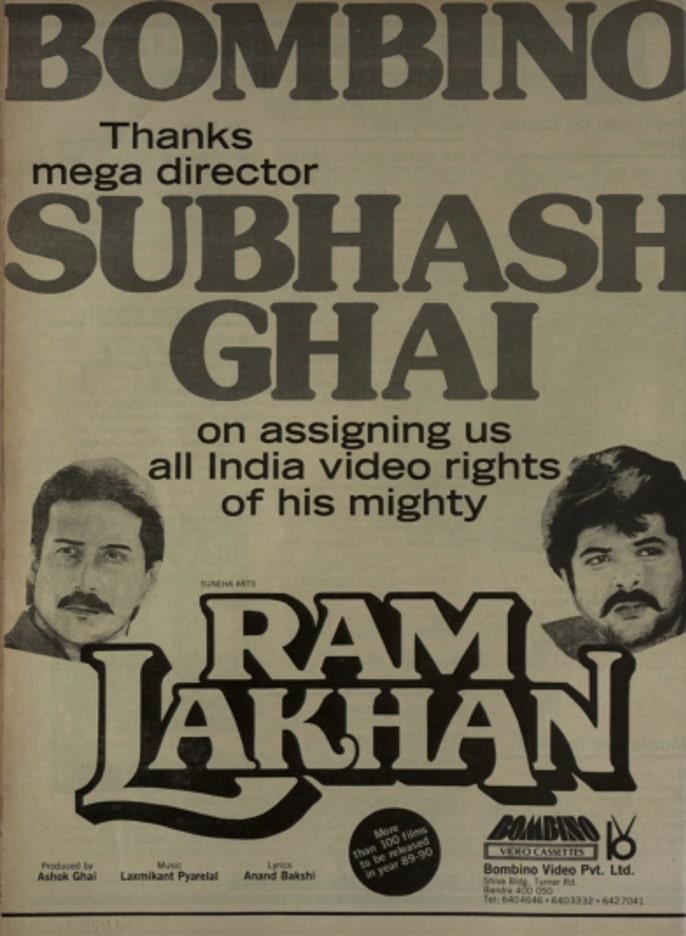

An announcement by Bombino Video Cassettes acknowledging director Subhash Ghai for assigning the company legitimate video rights of his theatrically released film Ram Lakhan, as published in TV & Video World, January 1989.

To read about authorship and authenticity in the case of the digital image, click here and here.

All images courtesy of National Film Archive of India (NFAI).