Witnessing Us: On Hum Dekhenge, a Photo Document

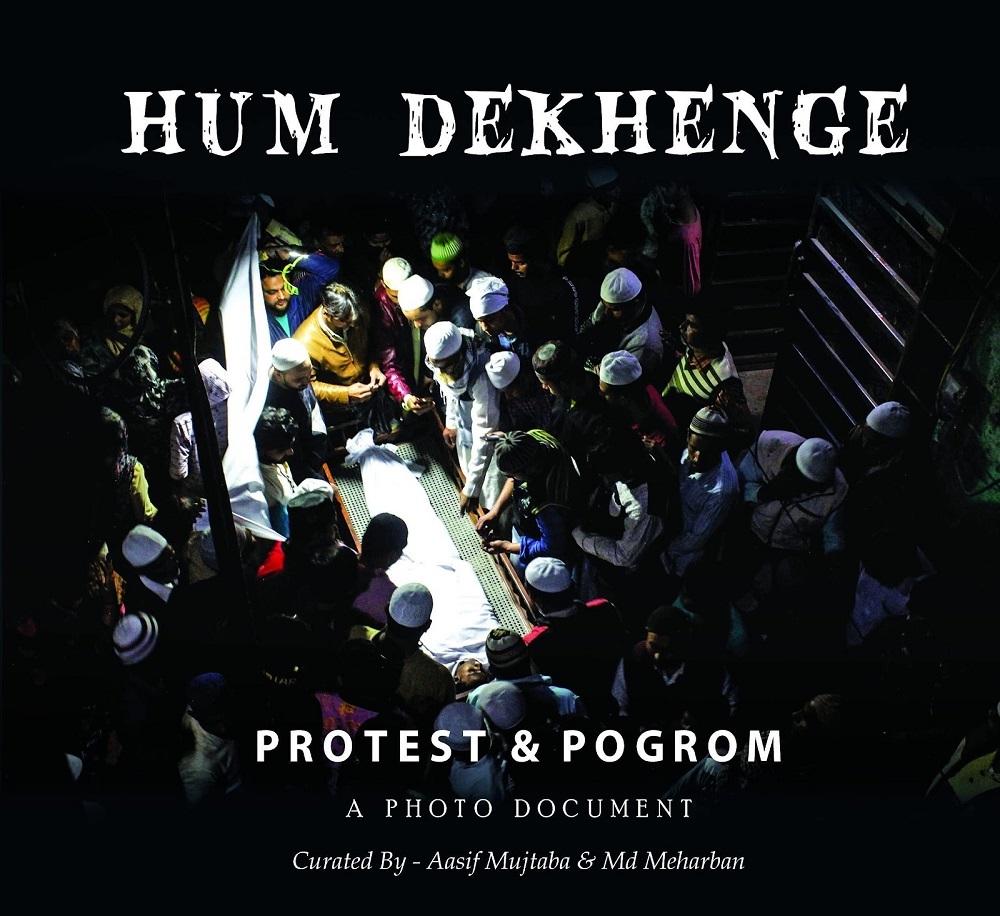

Curated by Aasif Mujtaba and Mohammad Meharban, Hum Dekhenge is a photo document featuring a collection of photographs taken during the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) protests that were organised in New Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh neighbourhood in late 2019. The protests were held immediately after the contentious bill was passed into law as an adjunct of the National Register of Citizens (NRC), aimed at the clear objective of denaturalising Muslim members of the population.

However, as the Supreme Court lawyer Prashant Bhushan puts it in his foreword to the book, “Though they began as predominantly protests with participation of Muslims who were fearful of losing their citizenship, they soon galvanized large numbers from other communities as well, especially from the youth and students who were concerned about this brazen assault on our secular polity.” Early organisers of the protest included student leaders and activists like Mujtaba and Sharjeel Imam. In the eyes of a conservative, middle-class population wary about the struggle for the assertion of rights through large, obstructive protest movements, figures like Imam posed both a threat and a romantic possibility of reform. The threat was activated by the steady drip of discourse fed into a radicalised mainstream media that saw politically vociferous Muslim men (especially students) as a danger to peace and stability. Equally, among liberal-secular supporters of the protests (admittedly, a shrinking sliver of the population), the romance of political agitation was legitimised by their backgrounds in well-recognised national educational institutions that are taken to be bastions of “merit,” like the many outposts of Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) or Jamia Millia Islamia. Imam, for instance, had studied at IIT-Bombay, before moving to Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

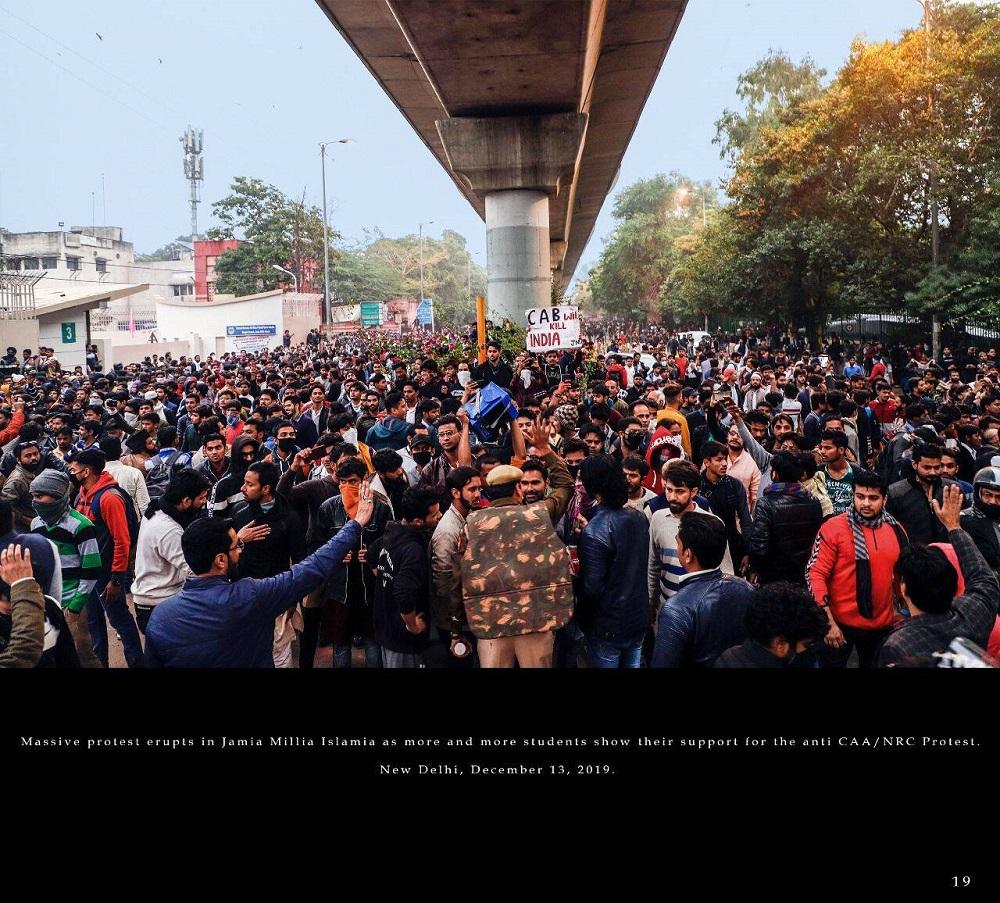

Universities such as Jamia Millia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University were at the forefront of organising the resistance against the CAA after facing the brunt of police atrocities on student-protestors. However, what actually pushed the movement out of the confines of liberal arts universities and Muslim ghettoes was the participation and political initiatives taken by large numbers of ordinary—often uneducated—Muslim women such as Bilkis Bano (fondly known as Bilkis Dadi), who became the popular face of the movement. Public presence, occupation, compassion and the will to struggle, quickly came to replace a narrative of simple political recognition—launching the movement into the realm of a popular struggle that affected almost every Indian citizen.

Students of Jamia Millia Islamia University faced the brunt of police violence during their early peaceful protests in December, 2019. Their campus was also targeted and violated by the police. Image courtesy of Farhan Khan.

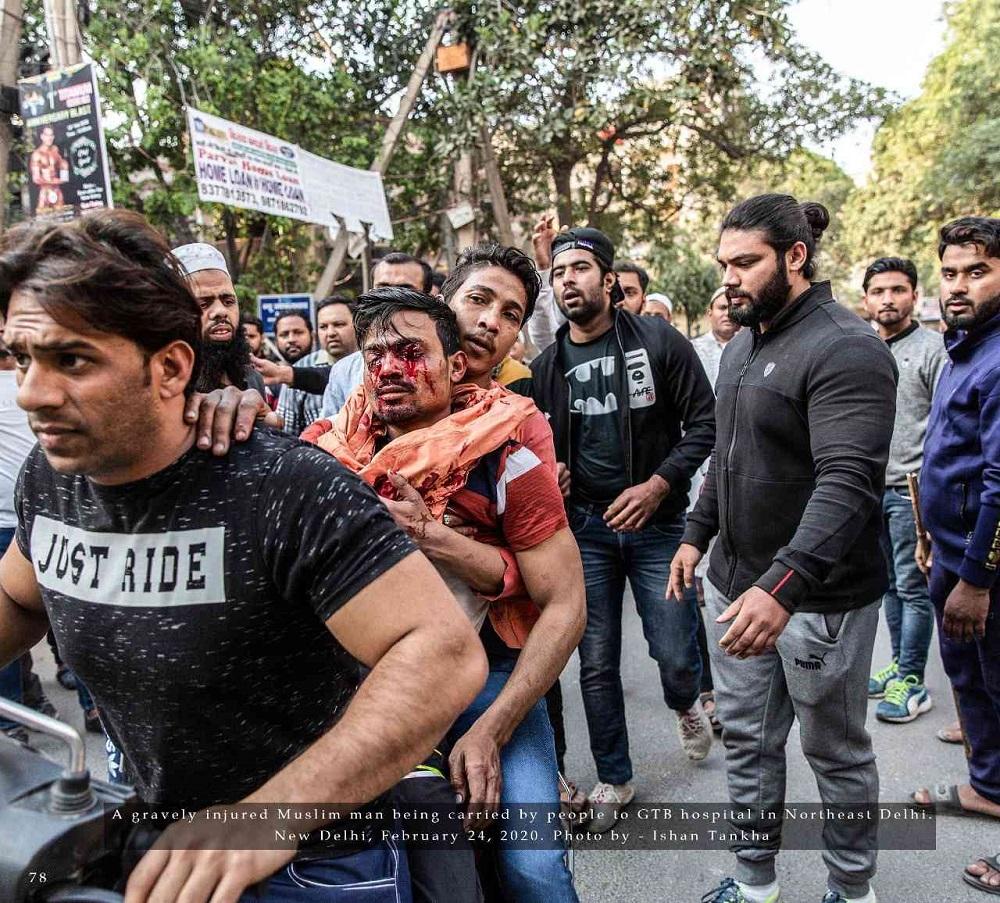

The work of photojournalists like Meharban, with several other contributors credited, including Ishan Tankha, Kamran Akhtar, Maryam Tariq and Rehan Khan, point towards the difficult process by which this trajectory was achieved. The book is also dedicated to photojournalist Danish Siddiqui, who was killed while covering a clash between Afghan security forces and Taliban fighters in Afghanistan in July 2021. With the three movements identified by Mujtaba as Protest, Propaganda and Pogrom, a clear narrative line is drawn from the passage of the Act, the initiation of protests, and the thick swarm of propaganda that prevented the truth of the movement from spilling out of its confines, to the organised anti-Muslim riots conducted in North-East Delhi during the run-up to that year’s state elections. By 24 March 2020, the protest sites had been cleared, owing to the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent nationwide lockdown.

A group of women protest against the CAA on the Jamia Millia Islamia University campus. Image courtesy of Shakeeb Kpa.

The photographs in the book are largely confined to the protests that took place in Delhi’s Jamia Nagar, including Shaheen Bagh, and the following rallies organised near the Jama Masjid, among others. Many of the photographs are graphic in nature, witnessing the brutal assault unleashed by armed policemen on peaceful protestors, the extensive damage inflicted on campuses like Jamia Millia Islamia and fragile acts of solidarity in the face of such violence. Due to the craft of photojournalism that encourages the immediacy of experience, the events achieve a political skin even when empty, disheveled rooms are depicted. The churning and violence are committed not just upon human bodies—of which there are plenty of depictions—but also upon spaces in the city, and monuments like the Jama Masjid, which is transformed into a site of resistance where the large shapeless mass of protestors acquire a definite form in our political imagination of a more resistant community to come.

Shaheen Bagh’s sit-in protests inspired many across New Delhi and far beyond. Protesters had to deal with violent reprisals, leading to their ultimate withdrawal in March, 2020. Image courtesy of Ishan Tankha.

Maktoob Media’s screenshots of CCTV footage depicting students being lathi-charged by the police create a further sense of anxiety. With such turn of events, state apparatuses committed to secure its citizens are turned against those lofty motives to keep certain citizens outside the radar of visibility. Hum Dekhenge turns the popular, eponymous song, written by Faiz Ahmed Faiz, frighteningly against its own secure belief in witnessing injustice outside of itself, into a more dangerous proposition where citizens of the republic are blamed for witnessing such atrocities in silence. In tandem with the stark nature of the photographs that open the city of New Delhi up with various forms of violence, the modern Indian self is inextricably implicated in these images of horror.

A few weeks before the anti-CAA protests were officially disbanded, violence broke out in North-East Delhi. The riots led to widespread violence committed largely by Hindu mobs on Muslim residents, many of whom lost their lives or were injured. Image courtesy of Adnan Abidi.

To read more about the documentation of the pogroms in North-East Delhi following the anti-CAA protests, click here.