History’s Promise: On Suneil Sanzgiri’s At Home But Not At Home

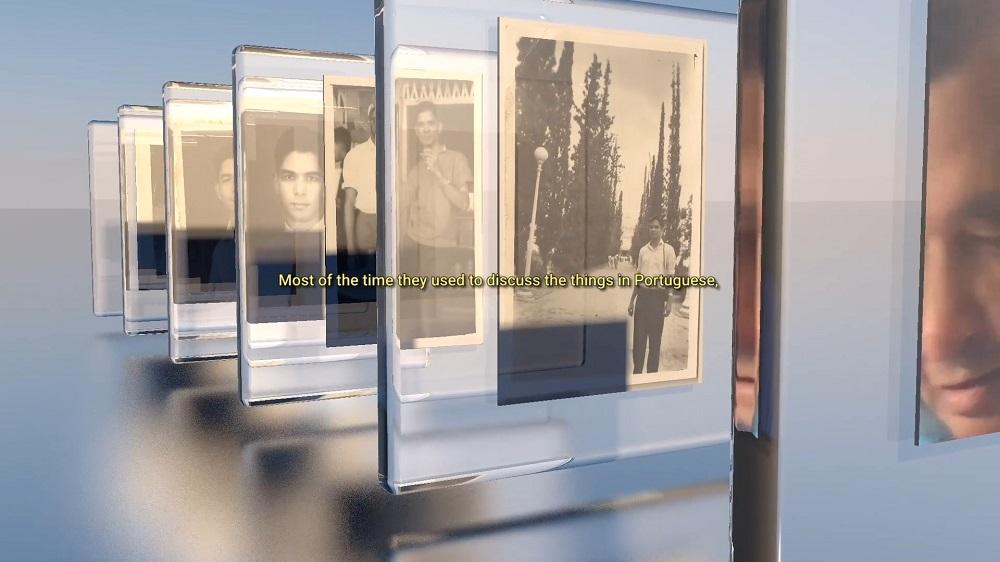

Suneil Sanzgiri’s short film At Home But Not At Home (2019) attempts to piece together a narrative of identity-formation for the Goan diaspora that has been put through several traumatic upheavals during the anti-colonial movements that took place across the globe during the mid-twentieth century.

The filmmaker’s father lived in the town of Curchorem in the southern part of Goa until the age of eighteen. He moved to Bombay in 1961 upon hearing about the Indian Armed Forces repelling the last remaining colonial armies sent by Portugal. The army itself was made up of a diverse set of people from Portuguese colonies such as Angola and Mozambique, thus making the task of forging anti-colonial (and racial) solidarity even more difficult.

In the film, while Sanzgiri invokes the promise of the Bandung Conference of 1955 that spelled the greatest chance of such a political solidarity being forged against imperialist and neo-colonial forces of the global north, he understands the failure of the promise as well. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s presence at the conference is comically re-appropriated, with his hand being isolated and cropped out of the image, as if to suggest the loneliness of his ideological position on the graph of world history. Sanzgiri uses a variety of tools and methods to put his fragments into cinematic shape: these include animation, drone photography and screen recordings of Skype conversations and Google Earth locations. He also incorporates archival images, including those from Indian films of the past that reflect on the Goan experience as a microcosm, further reflecting larger patterns in the Indian and global resistance to colonialism.

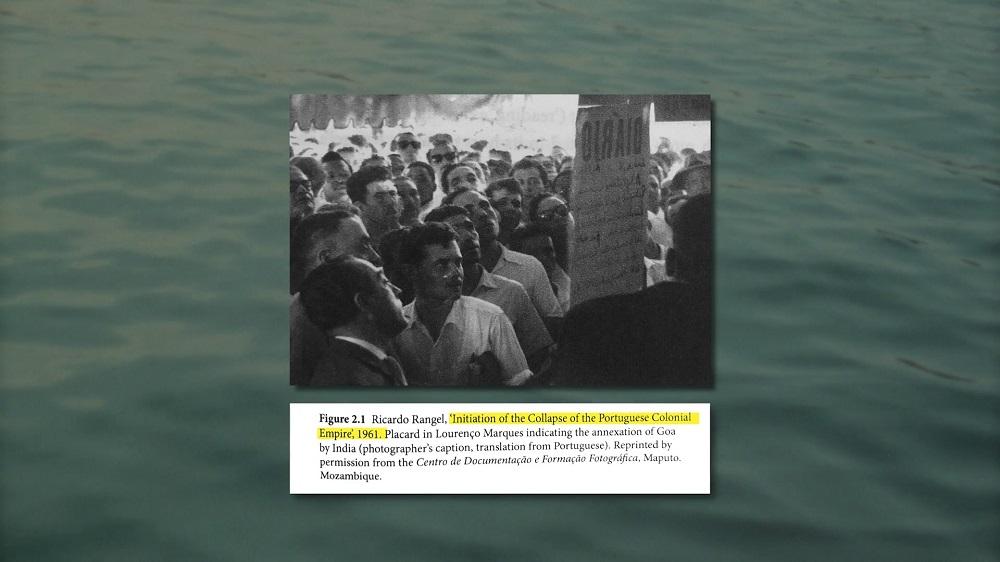

In order to portray these nascent connections being birthed by anti-colonial movements, Sanzgiri quotes a famous and striking photograph taken by Mozambican photojournalist Ricardo Rangel. Titled Initiation of the Collapse of the Portuguese Colonial Empire, the photograph portrays a group of men clustering in front of an announcement posted at Lourenço Marques (present-day Maputo, the capital city of Mozambique) in December 1961, marking the formal end of Portuguese rule in Goa after 450 years. Among the predominantly white, Portuguese men are a few Goan and Mozambican men as well, leading Sanzgiri to ask:

“What did the crowd see, looking up at the sign

announcing Goa would no longer be under colonial rule,

huddled together in Portuguese occupied Mozambique

when their own liberation movements were only moments away?”

Sanzgiri unearths images that describe the slender threads tying potential locations of resistance across the Indian Ocean. His efforts provide a way to counter the colonial employment of disparate populations in military adventures to maintain their regimes of power and control. Against such a narrative of occupation, Rangel’s photograph offers the possibility that Goans and their fellow-colonised will find a way to transition from anti-imperialism to confident self-assertions of cultural identity, without collapsing into nationalist tropes of violence and exclusion. These dreams of a more equitable future provide a map of the time, as Sanzgiri’s father remembers his subsequent exile in the United States— facing racial hostility—and feeds into the identity of the filmmaker who has only known Goa from stories, memories and images. He has never visited the state himself. The images of the aerial drone serve to heighten his feeling of loss, working as much as a distancing device over landscapes tied together by railway tracks or natural environments, as something that promises proximity to the land of his family.

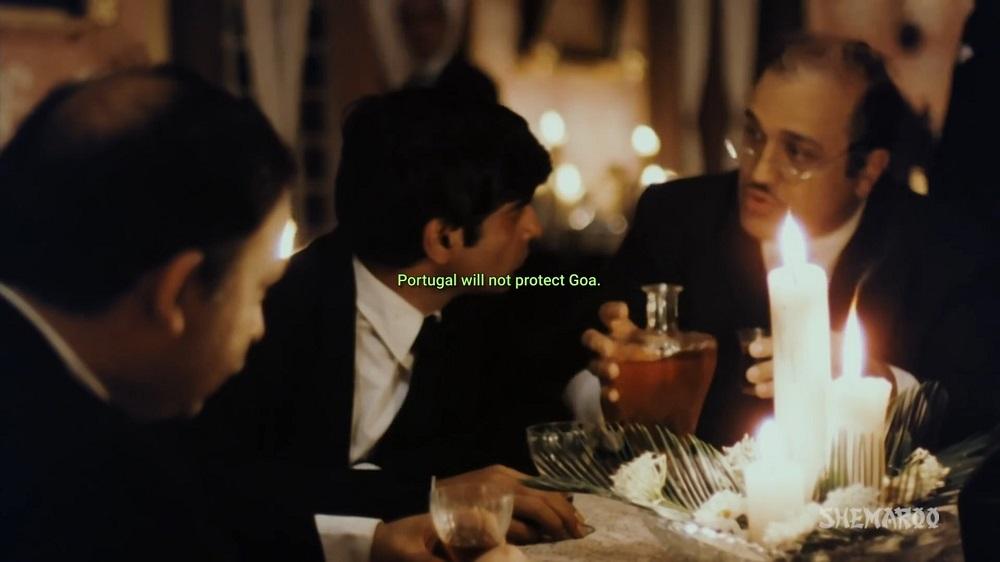

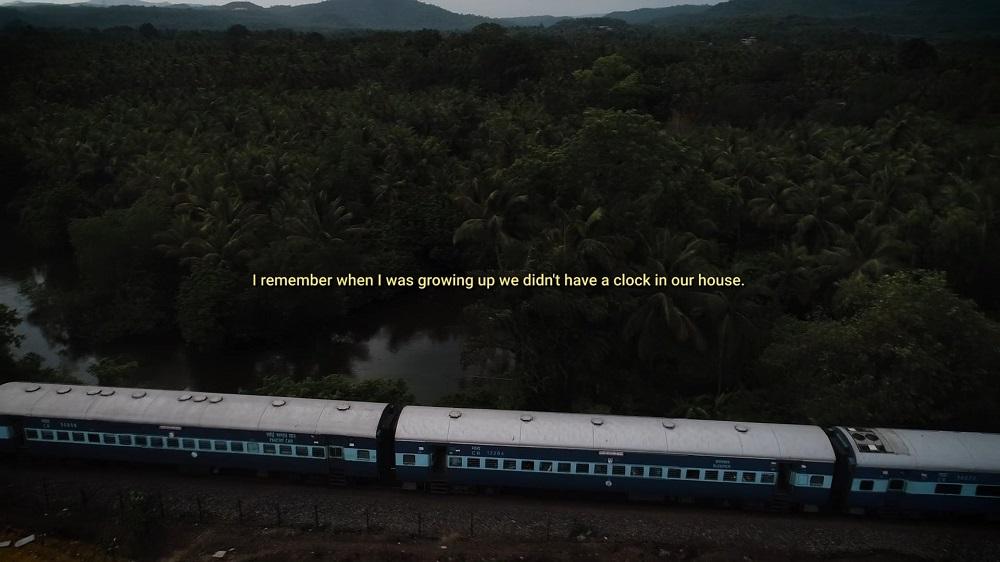

Sanzgiri’s search for Goan identity, forcibly forged in exile in his case, also takes him through the development of common tropes in Indian cinema that are intimately related to his father’s memories of Goa. The trains were a way of tracking time, as clocks were scarce in their household. This made Sanzgiri interrogate the great symbolic resonance trains have struck to mark the time of modernity in Indian cinema, quoting scenes from Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955), Nayak (1966) and Sonar Kella (1974). In another instance, a scene from Shyam Benegal’s Trikal (1985) is quoted depicting the anxieties of Goan Catholics during the struggle between the Indian army and the Portuguese occupiers. From realism to heightened fantastic narratives about Goan history, Guru Dutt’s colonial period epic Baaz (1953) is also invoked for its striking visuals of ships on fire off the coast of Malabar. Sanzgiri puts together a wide array of sources that have shaped the modern diasporic self of the Goan people. As his father’s memories play out over these fragments, the task of building a critical identity that is primed to inherit the failed promises of anti-colonial struggle, while remaining aware of how fragile minority identities are in postcolonial nation-states today, emerges piecemeal from the rubble. It is neither Goa nor the United States (where the filmmaker lives) that provides a perfect safehouse for Sanzgiri’s imaginative biography of the Goan self in the final account. It suggests that the past is the foreign country that he truly yearns to belong to.

To read more about the family as a repository of layered histories against the larger backdrop of migration and identity in Goa, please click here and here.