The Emergency and Stardom in India: Crackdowns on Creative Liberty in the 1970s

On 25 June 1975, the Indira Gandhi-led Congress government announced a state of Emergency across India. The Emergency remained in effect until 21 March 1977. During this twenty-one-month-long period, the state introduced several new censorship rules that suspended shooting films abroad and hosting film parties, along with curbs on representations of sex, alcohol, drugs and violence onscreen. These curtailments also limited the length of films and controlled the rhetoric of the film press. The censorship regulations were a subject of frequent discussion in film magazines between 1975 and 1977—a dark period in independent India’s history—sometimes as gossip or sarcasm, and sometimes as serious statements.

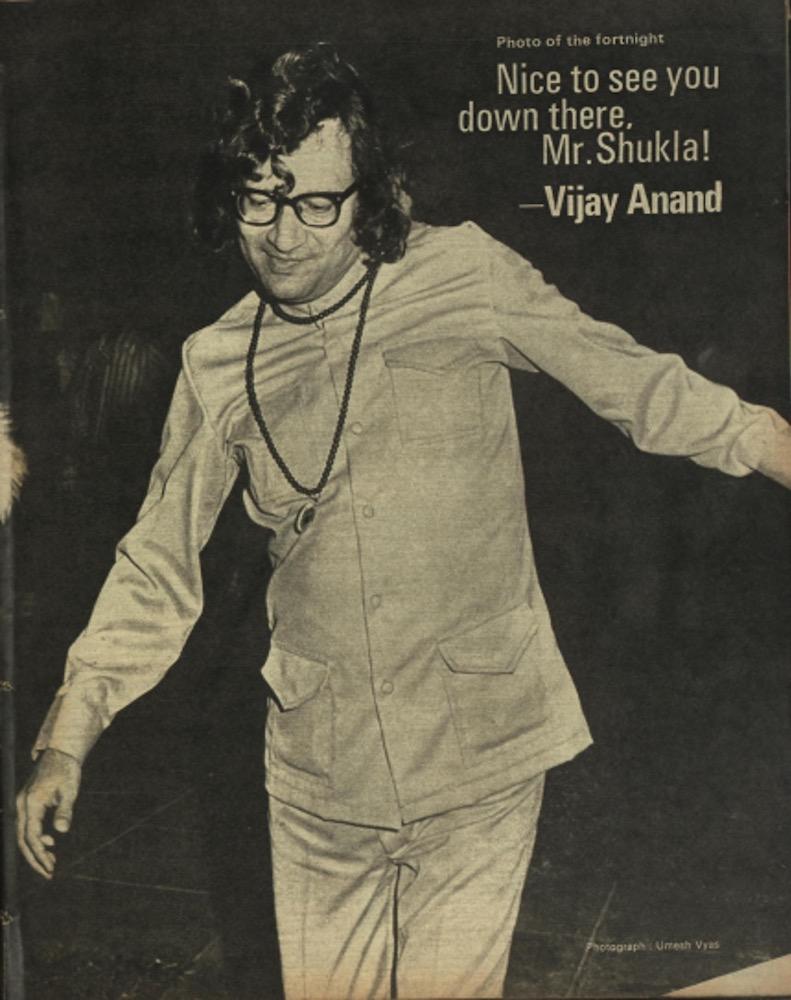

Vidya Charan Shukla was the Minister of Information and Broadcasting in India during the Emergency (1975-77). Filmfare, 1-14 April 1977.

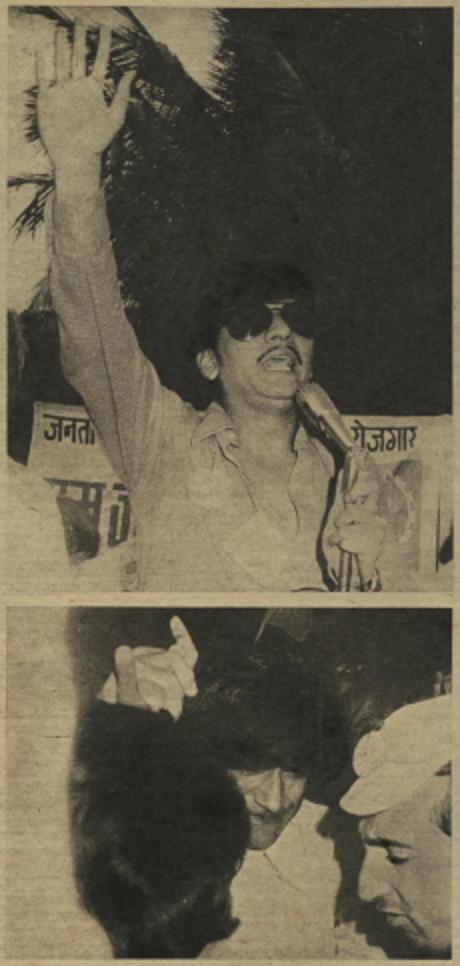

An early instance involved a memorandum published by editors of all film magazines. It sought to safeguard the autonomy of the film press in India, stating, “An enlightened objective censor and responsible, duty conscious film journals.” The disenchantment caused by the gagging of the film press found a voice in disgruntled movie moguls. The industry and the press subtly supported each other through the Emergency. Bolstering the film industry’s angst, especially following the assault of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) on producer-director O.P. Ralhan’s films, the magazine Filmfare, in April 1977, captured the sentiments of anti-incumbency by highlighting: “Film stars and industry leaders mustering unprecedented courage and reciting to the world at large the story of humiliation and blackmail they had suffered at the hands of politicians in power...” Notable film personalities like Vijay Anand, Pran, Danny Denzongpa, Shatrughan Sinha, Moushumi Chatterjee and Amol Palekar actively rallied for the amalgam of parties opposed to the Emergency, and the Janata Party’s win at the post-Emergency general elections. Their seething anger crystallised into a sustained effort to oust the Congress, especially “the villain of [their] nightmares,” Vidya Charan Shukla, the Minister of Information and Broadcasting, from power after the Emergency was lifted in 1977.

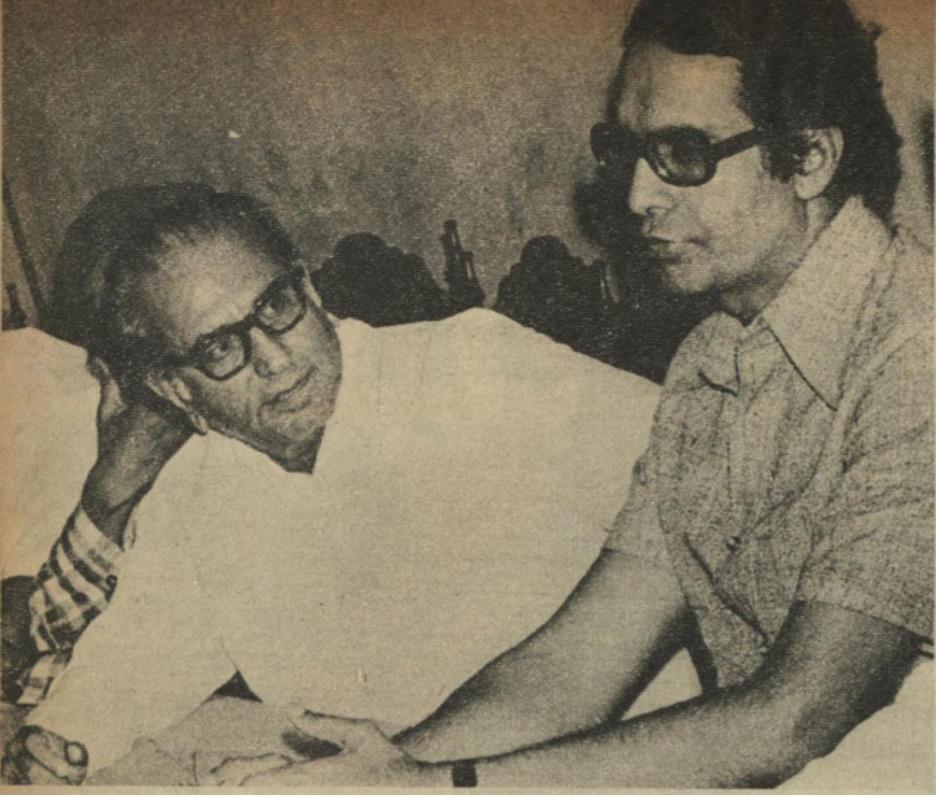

V.C. Shukla drew the attention of film tabloids that frequently published lurid pieces about his highly orchestrated private life. His friendship with Sanjay Gandhi prompted him to ban Kishore Kumar from All India Radio (and threaten to ban Lata Mangeshkar too) when the singer “disobeyed” and refused to perform at a Congress event for Doordarshan. The most famous of his private indiscretions was the “Candy Scandal” that shook the Film and Television Institute of India’s (FTII) integrity. Candy, also known as Vijaya Kumari, a woman from Himachal Pradesh, formed “a close camaraderie” with Shukla who foisted her on FTII for “dance and movement classes” without any formal institutional selection. Students from FTII went on a strike against the director Jagat Murari (a formerly dismissed and corrupt director, unfairly instituted by Shukla after dismissing V.K. Murthy), who silently supported the minister-sponsored Candy’s “lousy dancing” as part of a convocation show broadcast on Bombay television. A team of Filmfare reporters probed into the scandal in 1977. They visited Kumari’s house in the village of Masabra, where the woman says, “I am a scapegoat between the ruling party and the Opposition, that is the Congress.” Another name that emerged from the conversation was that of G.P. Sippy, a movie magnate who had advocated for a film role for Candy. Sippy was also known for his unwavering support for the Congress and his friendship with Shukla.

Movie magnate G.P. Sippy with former I & B Minister V.C. Shukla. Filmfare, 29 April-12 May 1977.

It was not just Sippy from the film industry who supported the juggernaut of Shukla’s censorship. The latter’s obsession for shutting down the film press started when Amitabh Bachchan had complained to his “boyhood chum” Sanjay Gandhi about some meddlesome journalists. Manoj Kumar, a political allegiance-hopping filmmaker, became the press’ butt of ridicule when he shelved a film called Naya Bharat that he had tried to make when the Emergency was declared in 1975 to instigate audience support for the Indira-helmed regime. As soon as Indira Gandhi lost the election in 1977, Kumar launched Kranti, a film extolling Jayaprakash Narayan, and even arranged to meet the man using Shatrughan Sinha as a mediator. Moreover, non-industrial, new wave and documentary filmmakers such as Sukhdev, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Chidananda Dasgupta, and the Films Division’s own staff were lined up to make short films in the series titled “Film 20,” to boost Sanjay Gandhi’s 20-point programme.

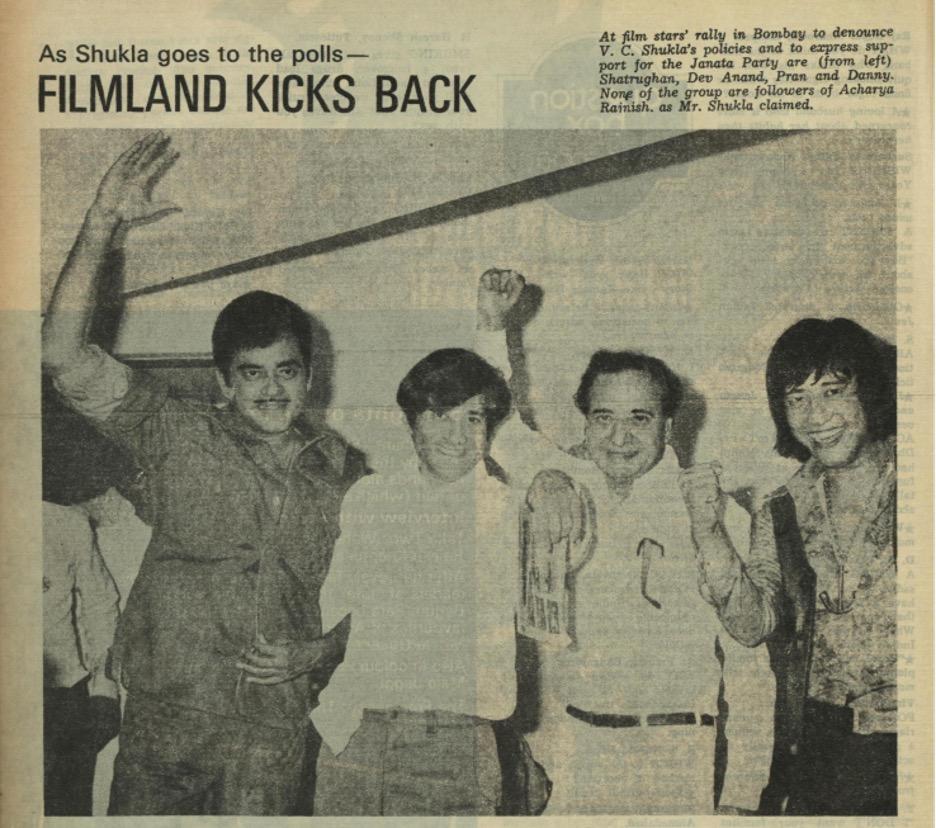

(L-R) Actors Shatrughan Sinha, Dev Anand, Pran and Danny Denzongpa at a rally in Bombay to denounce V.C. Shukla’s policies. Filmfare, 1-14 April 1977.

A letter to Filmfare in 1977 reminded its readers that the threat of being throttled were heightened by many industry insiders: “Remember all those photographs of Youth congress rallies with Dilip Kumar smiling vacuously at Sanjay Gandhi?” Yet another letter was published in The Illustrated Weekly of India in response to the paper’s feature, “Stars in Collision” (10 April 1977). It aimed to publicise the photograph of four film personalities (Shatrughan Sinha, Dev Anand, Pran Sikand and Danny Denzongpa, at the film stars’ rally in Bombay (13 March 1977) to denounce the Congress rule, stating: “Since when have these stars, who live and thrive on black money, developed a conscience? These people, together with smugglers, hoarders and adulterers, were scared to death during the Emergency because of their black deeds. It is not their love for JP but the hope of getting away with their misdeeds that prompted them to join the Janata bandwagon.” The Emergency, thus, threw up some conscientious readership, and, by extension, a critical public sphere.

Actors Shatrughan Sinha (top) and Dev Anand (bottom) at a Janata Party rally in Bombay. Filmfare, 8-21 April 1977.

Ram Jethmalani with actors Shatrughan Sinha (left) and Pran (right) at the Janata Party rally. Filmfare, 8-21 April 1977.

To read more about instances of state-imposed limitations towards lens-based practices in South Asia, click here and here.