Metamorphosising City: Bengaluru’s Public Sector in Cinema

A cursory online search of ‘Bangalore’ would immediately invite a plague of epithets such as ‘Silicon Valley’ and ‘IT Hub,’ or more prosaic ones like ‘Pensioner’s Paradise’ and ‘Garden City’. In the stupor of what social scientist Narendar Pani describes as a “culture of amnesia,” it would strike most people as unusual that Bengaluru, or Bangalore, as it was called until 2014, was the largest unionised public sector city in India until economic liberalisation in 1991.

If the city was to be labelled after its organised public sector history—which is unlikely, given how unfashionable it sounds—it would still retain a certain vacuous character that the others possess, confusing the steady march of capital and post-colonial developments for assorted essentialising shorthand. For instance, could Davangere in central Karnataka—a city supporting large-scale textile manufacturing and a trading centre for cotton—pull up its bootstraps and become the next global destination for cheap IT outsourcing in the blink of an eye?

Left: A Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) aircraft. HAL had a unit located in Eastern Bangalore’s Domlur township in the pre-Independence era. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Right: The HAL main gate, 1942. Image Courtesy of the HAL Heritage Centre & Aerospace Museum, Bangalore.

The Nehruvian era, or the formative years of independent India, witnessed the initial push to forge Bangalore as the hub of the nation’s defence capacities. Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (formerly Hindustan Aircrafts Limited) had already commanded a presence in the city, its unit located in Eastern Bangalore’s Domlur township, during the pre-Independence era. The rationale provided for public sector undertakings such as Bharat Earth Movers Limited (BEML), National Aerospace Laboratories (NAL), Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL) and Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) to have their headquarters in Bangalore was a simple one: the city’s safe distance from potential ‘aggressor’ nation-states like Pakistan and China. Another compelling reason was the highly skilled labour emerging from the many universities of the Madras Presidency and the princely state of Mysore.

Within Bangalore, historian Janaki Nair has written about the upper hand that many largely Tamil- and Telugu-speaking children of the colonial Bangalore Cantonment area had, compared to their non-university, pete- dwelling (or market-dwelling) contemporaries. These tensions would later manifest in the trade union movement in the city, with Kannada nationalists accusing public sector unions of being dominated by those from Kerala and Tamil Nadu, urging local and migrant Kannadigas to join Kannadiga outfits in the aftermath of the Karnataka Ekikarana Movement. While Bangalore’s foray into IT is often marked by the arrival of Texas Instruments in 1985, it wasn’t until the late 1990s and the early 2000s that the city’s Silicon dreams were finally congealed. The city owes its growth to many state subsidies in the purchases of land and, once again, the highly skilled labour emerging from its private engineering colleges.

The comments on YouTube for the Kannada film Arivu (1979) are filled with nostalgia for the neighbourhood of Jalahalli in northern Bengaluru, specifically the BEL School, which the cinematographer B.C Gowrishankar found ideal to suit the semi-rural backdrop of this ‘message’ film (as the South Indian term goes for any film tackling social issues). Jalahalli is a green, leafy suburb but is also home to several private industrial companies as well as Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs). Paved roads in the area lend themselves well to carefree afternoons, large parks and playgrounds have formidable tree cover and imposing water towers in the background, and there are well-appointed homes with modest garages. We see a vision of an Indian public sector suburbia; Blue Velvet without the subterranean malevolence.

A screengrab from the film Arivu showing the paved lanes of Jalahalli making way for casual afternoon bike speeding. (Katte Ramachandra. India. 1979. 126 minutes.)

While Gowrishankar had a checkered career in the Kannada film industry, he was manning the camera for what will probably transpire to be mainstream Kannada cinema’s last enduring hit Om (1995) that depicts a radically transformed ’90s Bangalore. He also inadvertently gives us one of the best glimpses into the dividends paid by a strong and organised public sector workforce in the late ’70s.

HMT stall at a fair.jpg)

A Hindustan Machine Tools Limited (HMT) stall at a fair. Image courtesy of HMT Photo Archives.

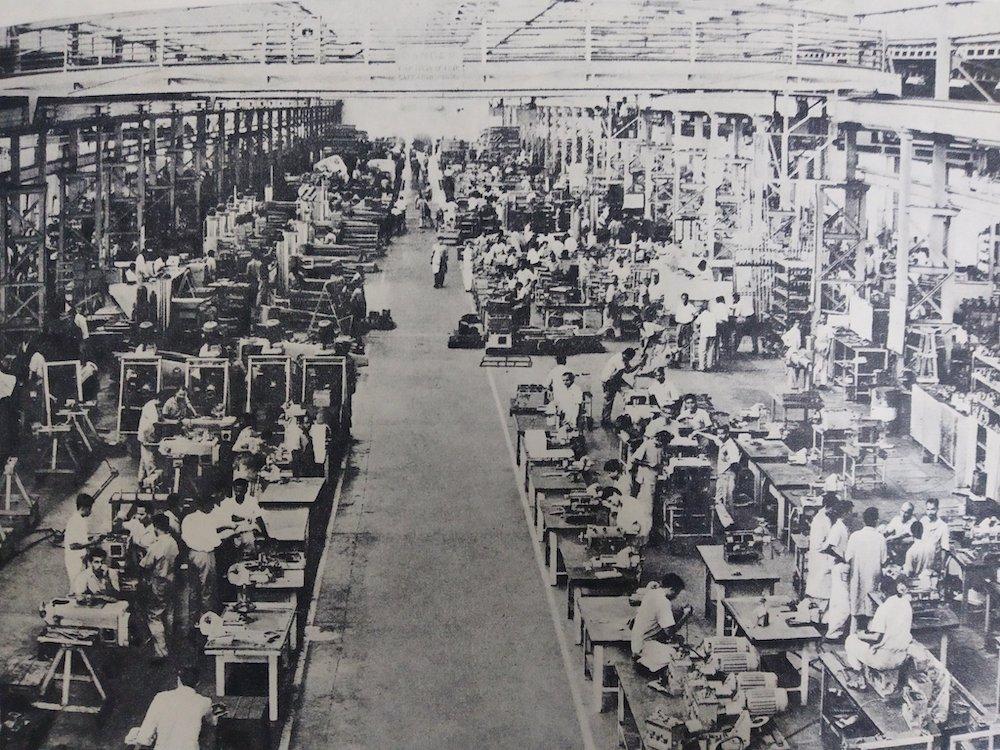

The shop-floor of the HMT factory. Image Courtesy of HMT Photo Archives.

M.S Sathyu’s film Galige (1994) shows us the same neighbourhood, but what we observe here is a vision of Pompeii; the glimpses of an idyll moment before swift decline. For starters, the protagonist Nitya is a worker at a thriving Hindustan Machine Tools Limited (HMT) unit, a PSU that has carried out an extended public funeral over the past two decades. Nitya is an orphan, but her job offers her a spacious, independent home that even manages to accommodate an elderly couple claiming to be her grandparents; rather unimaginable for a privately employed watch-worker in the modern age. We see Nitya going on an expensive date with a Japanese watchmaker roped in to HMT to improve efficiencies on the assembly line and collaborate on a series of watches. We also see her taking off at odd hours to roadside dhabas to meet a love interest whose past as a Khalistani forms the peripeteia of the film.

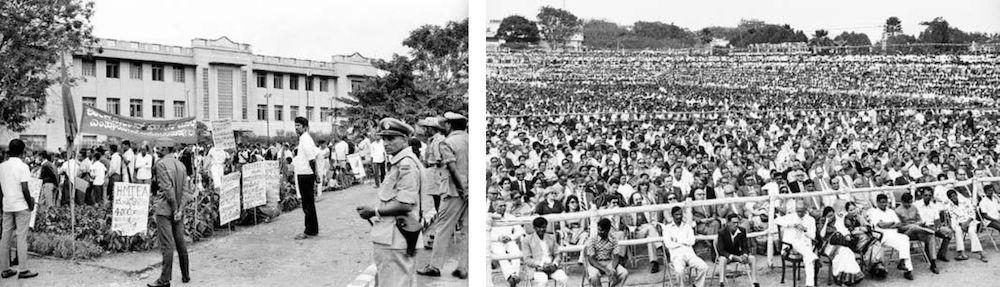

Left: A strike by the employees of HMT in the 1970s, demanding judicial inquiry against the management. Photograph by veteran photojournalist TL Ramaswamy for Prajavani Newspaper. Right: Members of the public attend HMT’s silver jubilee celebrations.

Nitya_s home in Galige.jpeg)

A stcreengrab from the film Galige, featuring the character Nitya’s home. (M.S Sathyu. India. 1994. 147 minutes.)

Although Nitya is an orphan, she is very much the child of the environment that Arivu foreshadowed with its emphasis on dignified housing, excellent public facilities, access to free public education, among other things. She still reaps the benefits of an old regime in her defiant independence, her living standards and even her leisure. Interestingly, Sathyu gives us a twofold farewell, one of the visions of the organised public sector and another of the parallel cinema that produced ‘secular’ films like Galige.