M. Sain of Darjeeling: The Painted Photographs of Bengal

From the early twentieth-century, painted photographs were widely produced, distributed and collected. They represented a way of melding a style of painting with the practice of photography. Techniques of illumination were also learned from local traditions of manuscript making, which involved the use of squirrel-hair brushes and cotton swabs with dyes, pastels and watercolours. Paintings, whether they be large oil canvasses or smaller miniatures, were expensive for the common person at the time, but photography promised an affordable way of appearing to own one. Several photographers took advantage of this hybrid form, including M. Sain who had a studio in Darjeeling and was a resident there for forty years.

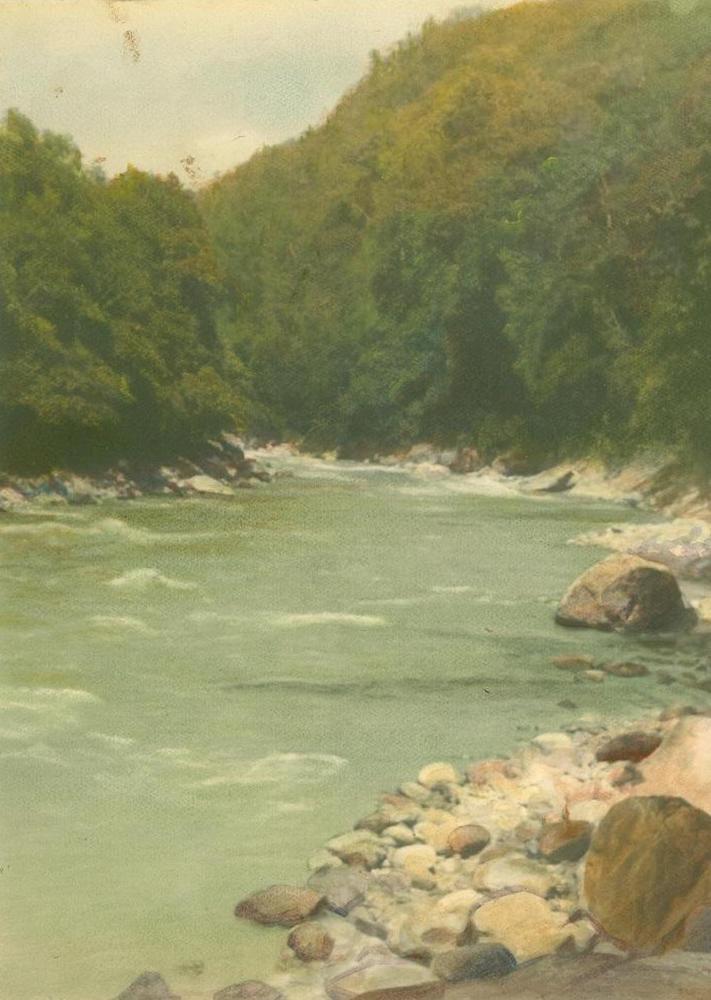

Hand-painted photograph of landscape. (Darjeeling. From the private collection of Kazi Anirban.)

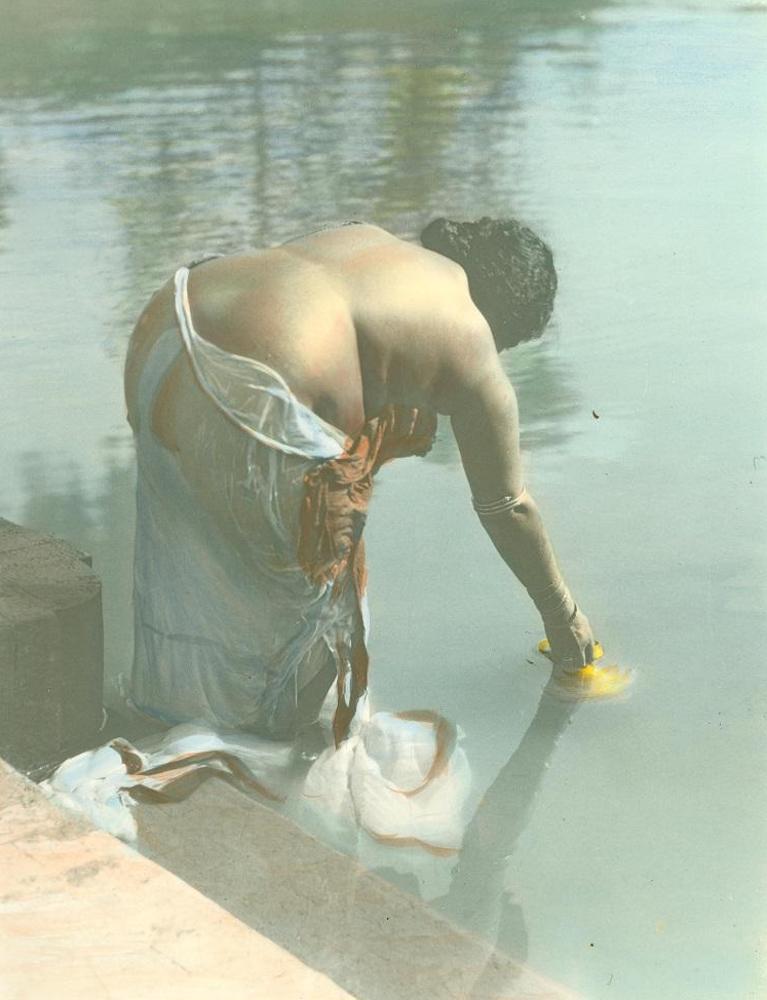

The painted photograph’s hybridity also extended to its use, which could suggest either a fanciful, erotic and enchanting investment in the subject, or a scientific gaze that sought to document people and landscapes “as they appeared.” M. Sain’s painted photographs try to absorb the creative potential in both of those traditions. He drew from the academic naturalism of painters like Hemendranath Mazumdar (1894-1948, b. Kishoreganj, Bangladesh) in his more erotic photographs, while he relied on the documentary aspects of his craft in projects that required an ethnographic approach. Colour is used sparingly in such photographs to isolate the flora and fauna, creating a textural difference between the two kinds of subjects included in the photograph: the vegetative and the human. As part of his efforts in amateur botany and ethnography, he also wrote books like Rhododendrons of Darjeeling and Sikkim Himalayas (1974).

Many of these hand painted photographs relied on the prestige and value of academic naturalism in painting—which they tried to replicate even at the cost of giving up the verisimilar aspects of the photographed image. (Darjeeling. From the private collection of Kazi Anirban.)

The erotic photographs are complex too, as they use the stylistic mannerism of (un)concealment that was perfected by Mazumdar. However, as several art historians have noted, Mazumdar himself used photographs as blueprints for his paintings. Even as the paintings gave the impression of movement and the noise of rippling flesh through the layered impasto of colour, they were carefully constructed in a studio. Sain returned these images to a different order of construction. Painting in the notorious “wet sari,” he also includes the golden chink of the vessel, half-submerged in the water. The slipperiness of the photographic surface, shifting between natural appearance and laborious artificiality, largely provides the erotic frisson in these images.

Ethnographic portraits borrowed from a slightly different genealogy of representations—relying on scientific methods and styles of depicting information about ethnic identities. (Darjeeling. From the private collection of Kazi Anirban.)

All images photographed and hand-coloured by M. Sain.