Lobby Cards: Preserving Cinema through Still Image

Before the age of television and the internet, much of film publicity relied on the still image; posters, lobby cards, song booklets, postcards and other printed material often featured photographs from the film. Of these, lobby cards were a unique form of advertisement: as the name suggests, they were smaller forms of posters that were displayed in the lobbies of theatres. The images on lobby cards were not, however, production stills. Rather, they were what film scholar Sabeena Gadihoke has called “rehearsed tableaus” or staged photographs—often made after filming had been completed—that highlighted dramatic moments from the film in order to build curiosity around it. The composite lobby card was a collaborative effort between the filmmaker, photographer and artist. The film still was mounted on a piece of cardboard along with the production credits and was often framed by a vivid graphic design.

Today, while lobby cards have lost relevance as publicity material, they have come to embody new meanings as art objects. Curator Rahaab Allana’s personal collection of film memorabilia contains, among other artefacts, lobby cards from the 1950s and 1960s, several of which represent relatively unknown works from Bombay cinema. Many of these films are no longer available in celluloid; their lobby cards, then, become material archives of an otherwise disappearing cinematic past. In their new role as art objects, they offer perspectives on older modes of filmmaking, genres and ideas. This essay offers commentary on six such objects from Allana’s extensive collection in an attempt to reveal their relevance as important records for the study of film history today.

Publicity Still for Makkhee Choos (1956). d. Ramchandra Thakur, p. Maya Movies. Ip. Mahipal, Shyama, Leela Mishra, Jeevan, Gope, Moti Sagar. 244 x 300 milimetres.

Ramchandra Thakur’s Makkhee Choos (1956) is the story of a wealthy miser (hence makkhee choos, a colloquialism for someone who is extremely stingy) named Maniklal (Gope) and his son Narayan (Mahipal). Along with his beloved Lakshmi (Shyama), Narayan hatches a plan to teach his father a lesson. What ensues is a comedic series of events involving a fake kidnapping, multiple marriages and much family drama. Interestingly, the image above reveals neither the plot nor the main cast of the film, choosing instead to depict another popular actor of the time, Bhagwan, instantly recognisable by his signature pose. The scene seems to be a dance sequence and Bhagwan, despite having not more than a guest appearance or a small role in the film, is centre stage. This was likely done in order to intrigue audiences and use Bhagwan’s popularity as a publicity peg.

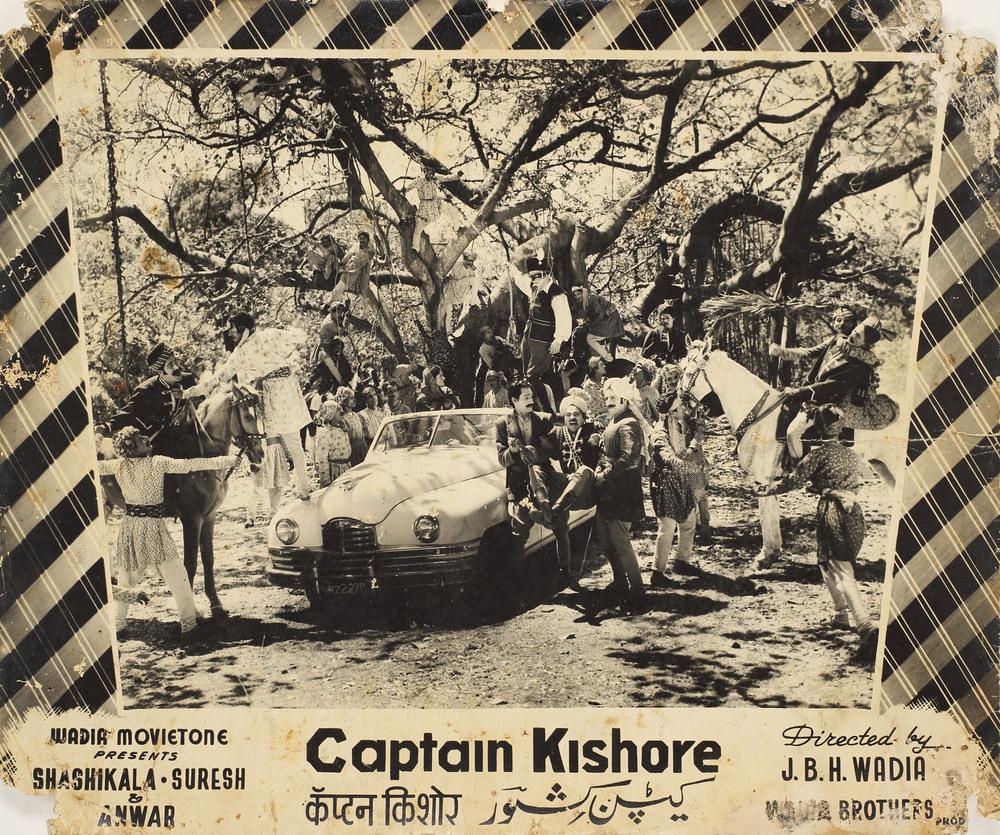

Publicity Still for Captain Kishore (1957). d. J.B.H. Wadia, p. Wadia Brothers and Wadia Movietone. Ip. Shashikala, Vijaya Choudhury, Suresh, Anwar Hussain, Naina, Roopmala. 253 x 303 milimetres.

From all the publicity material made for the relatively unknown Captain Kishore (1957), an action-thriller set in a fictional kingdom, this particular lobby card best represents its bizarre universe. The featured tableau has an assortment of disordered objects and people captured as though in mid-motion. The contrast of the textured border that frames it only adds to the chaos of the poster. The result is an almost surreal effect that reveals nothing of the film’s story and leaves the viewer wanting to know more. The art of capturing motion in tantalizing still frames was a characteristic of the lobby card, giving it the unique position of acting as a bridge between audiences and the film.

Publicity Still for Sher-e-Baghdad (1957). d. Om Sonak, p. Pyarelal. Ip. Nigar Sultana, Mahipal, Hiralal, Helen. 253 x 302 milimetres.

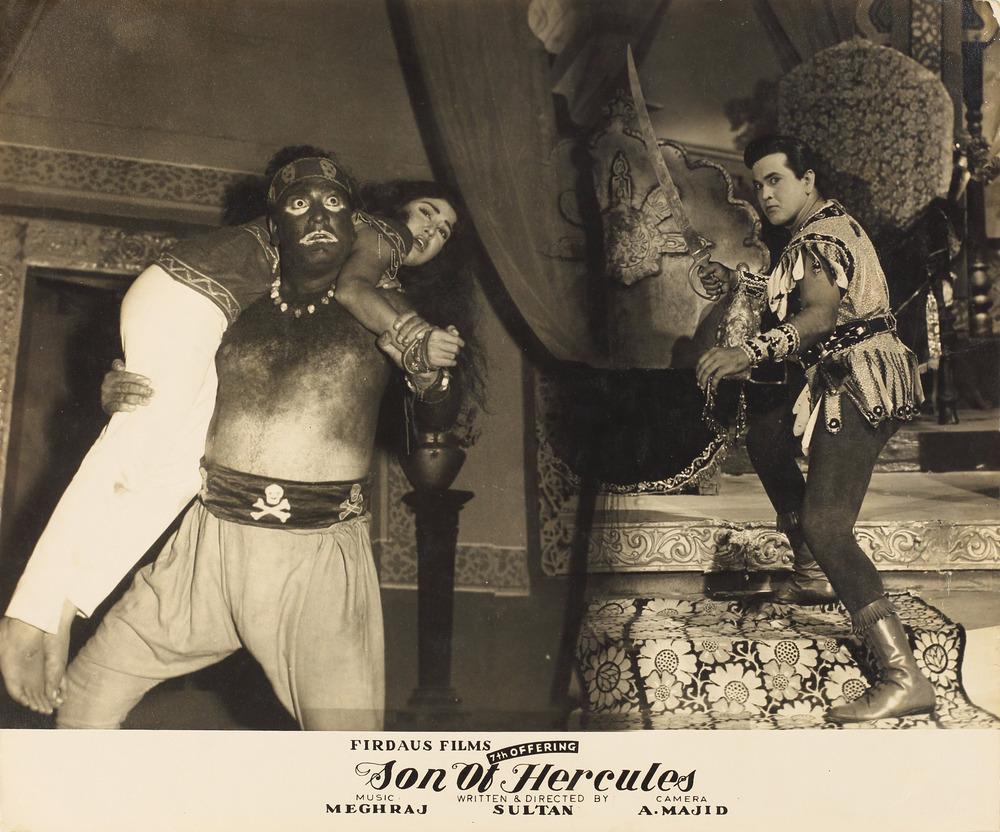

Publicity Still for Son of Hercules (1964). d. Sultan, p. Firdaus Films. Ip. Fazal Khan, Leela Kumari, Kenny, Master Shetty, Kamran Khan. 251 x 302 milimetres.

Another significant feature of lobby cards was its use of design and technology, however rudimentary, to contrast two or more images within a single frame. The two lobby cards above both highlight this, albeit in starkly varied contexts. The lobby card for Sher-e-Baghdad (1957) is enigmatic and somewhat sinister: the female actor is featured twice, in different avatars, and following Hollywood conventions, lit brighter than the rest of the frame. Her gaze dominates, almost as though to lure viewers in. It is only upon closer observation that one notices what seems to be a recreated scene from the film in the background, but this scene falters under the overwhelming stare of the heroine. The featured still for Son of Hercules (1964), on the other hand, is cruder, despite being made in the following decade: the merging of the two images is more apparent, as is its meaning. Whether the two images are from the same scene in the film is immaterial for the purpose of the lobby card; what is highlighted is the hero in action, fighting to save the heroine from the clutches of the villain.

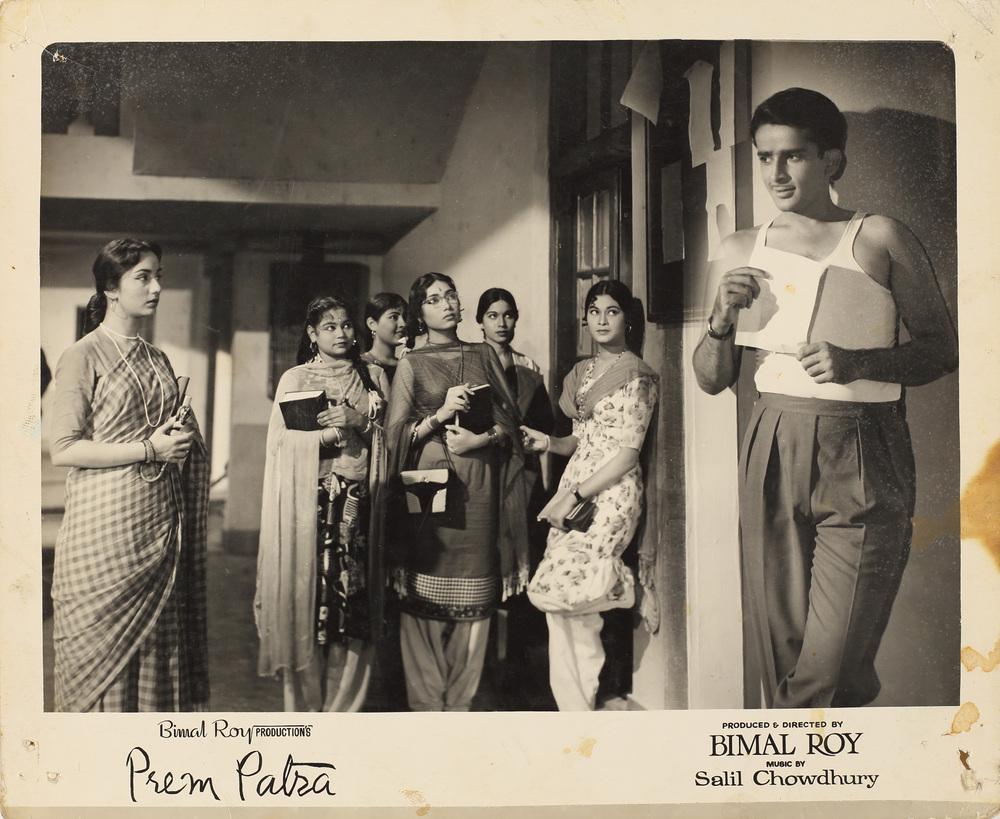

Publicity Still for Prem Patra (1962). d. Bimal Roy, p. Bimal Roy Production. Ip. Rajendra Nath, Sadhana, Chand Usmani. 246 x 300 milimetres.

The lobby card for Bimal Roy’s Prem Patra (1962), starring Shashi Kapoor and Sadhana, presents a contrasting picture to the others featured in this essay. The photograph is given prominence, framed as it is by a simple white border, with no graphic frills adorning it. Kapoor seems to be placed deliberately in the foreground, his characteristic boyish charm playing to the camera and, by extension, the viewer. The recipient of his gaze, however, is stern: Sadhana’s face betrays no emotion, much like the other women in the frame, likely her peers. The reference to the title of the film is apparent, as Kapoor toys with a letter in his hands—a prem patra, perhaps? What does it say? Why is Kapoor’s playfulness not echoed in Sadhana? What form will this love story take? The image opens the film to multiple possibilities, with several layers of meaning captured in one frame.

Publicity Still for Hum Sub Ustad Hain (1965). d. Maruti, p. A.V. Mohan. Ip. Ameeta, Dara Singh, Kishore Kumar, Sheikh Mukhtar. 251 x 304 milimetres.

The curiously titled Hum Sub Ustad Hain (1965), starring Kishore Kumar, Dara Singh, Sheikh Mukhtar and Ameeta, is a complicated tale of violence, fate and redemption. With several plot twists and unexpected revelations, the film ultimately negotiates ideas of honesty and the human spirit. The scenes (re)created for the publicity of the film draw on seemingly unrelated moments, intriguing without context. In this particular still, for instance, the viewer instantly becomes a voyeur, as one looks upon a scene of what is clearly attempted murder. Sheikh Mukhtar, who plays a villainous Romi in the film, is in focus, strangling a young woman as his cronies look on. It is a crime scene, and only the audience is witness, making them a part of the narrative even before they watch the film.

These lobby cards, though a fragment of Allana’s collection, give us a glimpse into the potential of film ephemera as alternative sources of film history. They are not material archives in the manner of celluloid; much of their interpretation rests on conjecture, assumptions, speculation, and therein lies their importance. They are extra-cinematic objects, offering perspectives that go beyond the film to reveal ideas about the people, technologies and desires that constitute film industries.

All images belong to the private collection of Rahaab Allana.