From Majestic to Gandhinagar: The Slow Decline of Bengaluru’s Kannada Film Industry

.jpg)

Majestic Bus Stand. A central transport hub of Bengaluru. (1980s. Image courtesy of Kailas Hoskote.)

Alankar. Kempegowda. Prabhat. Sangam. Kalpana. Himalaya. Kino. Swastik. Central. Sagar. Kailash. Tribhuvan. Kapali. One can walk around the area now renamed as Gandhinagar in Bengaluru and find no trace of any of these single-screen cinema halls that once dictated the fortunes of films released across the four dominant industries and languages of South India in Bengaluru. Earlier, a cinema hall named Majestic lent its name to the central transport hub of the city as well as its surrounding residential neighbourhoods, and what remains now in the theatre’s place is an empty plot. Majestic was also to Sandalwood—the centre of cinematic production for the regional Kannada film industry—what the neighbourhood of Vadapalani in Chennai is to Kollywood. This past is easily evidenced, much like an industrial ghost town, in the scattered presence of abandoned studios, distribution offices, poster printers and post-production studios. In the digital era, Gandhinagar rents out video equipment to all manner of independent directors, vloggers and short-film crews at all hours of the night, a service advertised in local dailies.

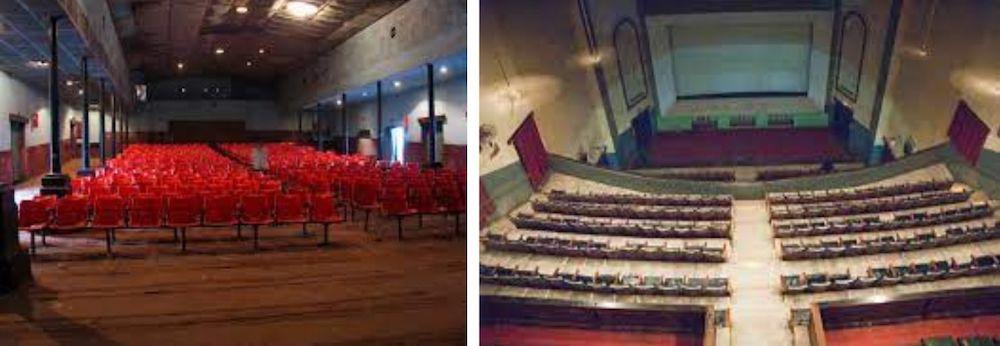

_.jpg)

Alankar Theatre in its heyday. (Image courtesy of Subbu Desai and Mandi Ganesh.)

.jpg)

The now-demolished Sangam Theatre which was once located in the Majestic neighbourhood where cinema culture used to thrive. (Image courtesy of Anup Shetty.)

As film historian Muralidhara Khajane noted, “The concentration of film-related activity in Gandhi Nagar began in the ’60s. Gandhi Nagar was just across the city bus stand and railway station, and it was easy for the thousands visiting the city—either a film buff or anyone in the movie business—to hop across to either catch a film or procure movies from producers. It was also easy for exhibitors to transport film reels from one theatre to another.”

The ambient state of decline is reflected in the condition of contemporary Sandalwood. Whenever something does make it to the news, it is scarcely a new mainstream film taking the state by storm but rather the lifting of a protectionist dubbing ban and the various incandescent reactions to it. The origin of this ban can be traced back to the 1940s or 1950s, with the birth of the Kannada film industry. It was separate from Madras, where most of the films were made. The ban did not, however, have any legal sanction; subsequently, actor Rajkumar then asked the film industry in Madras to refrain from dubbing films into Kannada in order to let the industry thrive. Later, in 1965, some exhibitors at Kempegowda Road committed orally that they wouldn’t screen dubbed films, and the practice continued. The ban was only lifted in 2015.

Left: The now-razed Plaza Theatre. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Right: The interior of the now-razed Elgin Talkies. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Another factor contributing to the decline of Sandalwood is the proliferation of television and newer forms of content production, such as YouTube and other OTT media platforms, which have managed to fill the large void left by the once-dominant film industry of Sandalwood. Small-screen production houses rent specially fabricated premises in residential areas, such as Rajarajeshwari Nagar and Nagarabhavi in Bengaluru to shoot tele-serials while modest film production houses and studios function from Nagarabhavi, Chandra Layout, Vijayanagar and Rajarajeshwari Nagar near the Mysuru-Bengaluru highway. This shift is characterised by the usual push-and-pull factors: lower rent rates, a largely decentered industry and numerous content-hosting platforms entering the picture. The closest that present-day Gandhinagar harks back to its past avatar is in the form of a popular song bar where most tunes, sung in Hindi, Kannada and Telugu, trace their provenance before the 1990s.

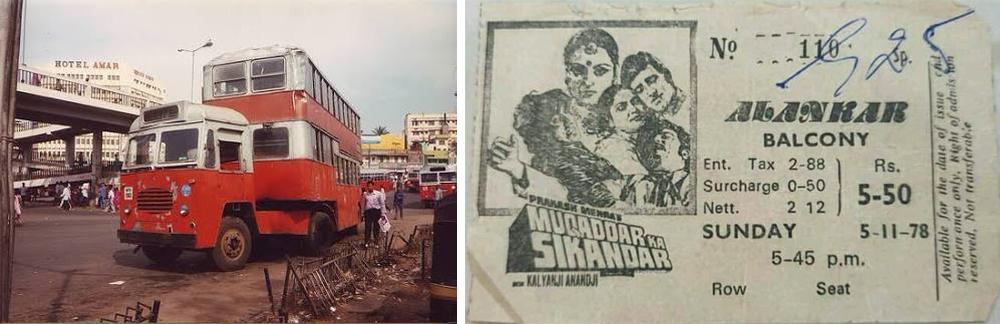

Left: A now-discontinued double-decker bus at the Majestic Bus Stand. (Image courtesy of PC Prajavani.)

Right: A ticket stub from Alankar Theatre for the Amitabh Bachchan-starrer Muqaddar ka Sikandar (1978. Image courtesy of Venkatraman Ramprasad.)

Most writing about the waning of Majestic and the cinema culture that once flourished there is attributed to the invasion of multiplexes. However, little is said of the stagnation of Kannada cinema, as significant sections of the audience opt for mainstream Telugu and Tamil releases, or engage with Kannada content on various online platforms. Certain Kannada films such as Thithi (2015), Balekempa (2018) and Pinki Elli? (2020) manage to find favour with festival-going audiences across the world, while pitch-perfect, almost poetic movies such as Gantumoote (2019) succeed in capturing the attention of the streaming platform market.

While the KGF franchise of period action films did stem the tide against a stagnant industry for mainstream Kannada cinema, other prosperous industries such as Tollywood (Telugu) seem to be more adept at adopting the better angles of the KGF blockbuster formula through efforts like Pushpa: The Rise (2021).

The last two decades of Kannada cinema have been characterised by its existential incertitude in the face of the unprecedented rise of neighbouring industries such as Tamil and Telugu, with audiences in Karnataka often lining up for the inflated-budget star-vehicles of the latter. The KGF franchise’s marked shift to a more pan-Indian audience doesn’t offer too much clarity on the path Kannada cinema must eke out for itself to stay relevant and appeal to its local audiences.

.jpg)

Majestic transport hub was conveniently located so cinema-goers as well as those working in the production of films could easily hop across to watch a film or procure movies from producers. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)