Ethnonationalist Impulses: Shankar Nag and the Cinema of Karnataka

Towards the end of the 2000s and the beginning of the new decade, Sapna Book House, a chain of bookstores with modest beginnings in the Majestic area of Bengaluru, began to stock a series of DVD titles. These titles emerged from a publishing house named Total Kannada whose website proudly proclaims, "Largest Kannada Shop". As someone making a spirited attempt of understanding the city and its culture, a relatively cheap DVD that usually carried “canonical” objects of Karnataka’s history in cinema proved to be an instructive purchase. It covered the oeuvres of prominent directors and actors through the eight decades of Kannada cinema. I ran through dozens of 3-in-1 DVDs priced at rupees forty-nine each, covering the work of actors Ambareesh, Vishnuvardhan, Rajkumar, Ravichandran and, of course, Shankar Nag. While most of these actors get their fair share of real estate on the many autos that ply in Bengaluru city, Shankar Nag’s presence diminishes most other displays of fandom among the city’s working class. It leads one to wonder how a Konkani-speaking Brahmin born in the coastal town of Honnavar—which, as another native writer and playwright Vivek Shanbhag noted, has closer ties to Mumbai than Bengaluru in terms of economic dependence—came to be the predominant visage one sees on Bengaluru autos?

.jpg)

A Shankar Nag sticker with the Karnataka State flag. (Image courtesy of Wikicommons.)

Shankarnag_s enduring visage on an auto (PC_ wikicommons).jpg)

Shankar Nag's enduring visage on an auto (Image courtesy of Wikicommons.)

Sushma Veerappa, former assistant to filmmaker and art director M.S. Sathyu, goes far beyond answering this question in the sublime documentary Shankar Nag Kelkond Bandaga (When Shankar Nag Comes Asking), quietly release in 2013 and also mysteriously appeared in the aisles of Sapna Book House. For a good chunk of the running time of 45 minutes, Veerappa manages to capture the contradictions that go into the making of a male-exclusive "Kannadiganess" through the words of the people arriving at that identity themselves. Her unobtrusive eye takes us to a sticker shop popular among auto drivers and reveals the wide range of actors whose cutout stickers they prefer to use as insignia on their vehicles. These include the Telugu actor Chiranjeevi and the Bengaluru-born ethnic Marathi Kollywood star Rajnikanth. While the proprietor of the shop acknowledges the popularity of the idols from other film industries, he also makes a sheepish attempt at asserting the predominance of Kannadiga stars. In another scene, an auto driver explains to a customer that he does his best to speak the languages of the people he is plying, be it Kannada, Hindi, Tamil or Telugu, and also simultaneously chides the passenger for bothering to seek out tourist spots in Bengaluru, asserting Mysore’s dominance as the cultural capital of the state.

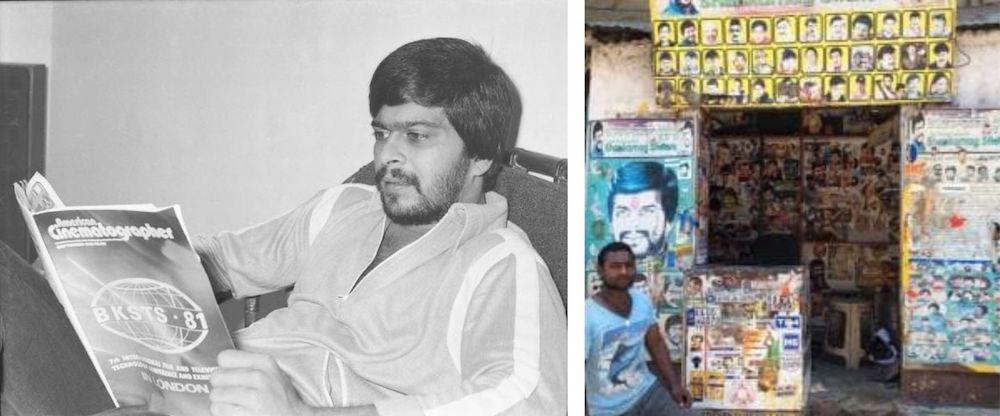

Left: Shankar Nag appealed to both working class and wealthy Kannadiga audiences. (Image courtesy of The Hindu Archives.)

Right: A sticker shop in Bangalore. (Image courtesy of Wikicommons.)

The movie features clips from various films starring Shankar Nag that aren’t didactically seeking connections with the ethnographic material that dominates most of the film. We see Nag’s star turn in Auto Raja (1980) which endeared him for decades to the working-class population of the city, as well as his more urbane roles in films like Nodi Swamy Navirodu Heege (1983) that earned him respectability in the genteel Kannadiga society. Veerappa slowly unravels Nag to the viewer, completely at ease with the unfurling contradictions on screen, essaying the jagged path towards stardom and employing gentle irony in the many aspects of social influence for which Nag clearly didn’t sign up.

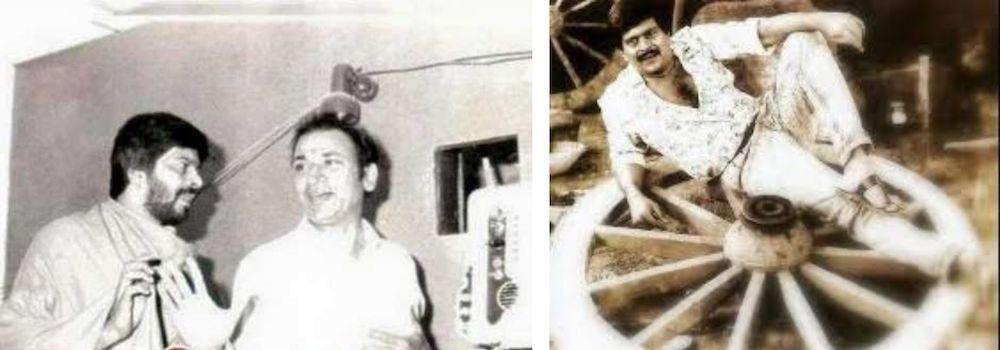

Left: Shankar Nag with Rajkumar, the doyen of Kannada cinema. (Image courtesy of Chitraloka Archives.)

Right: Shankar Nag in his later years. (Image courtesy of Prajavani Archives.)

To go a little further back, Nag embodies the dissonances of the Kannada unification movement in 1956 that probably led to his claiming a Kannadiga identity over a Konkani one, or a home in Sandalwood over Bollywood, as Nag did begin his career in Mumbai, in the footsteps of his brother Anant. The Karnataka Ekikarana Movement brought people from the erstwhile Mysore State, the Bombay Presidency, the Hyderabad State, the Madras Presidency and the Kingdom of Kodagu towards a common destiny, albeit a messy one that is still ironing out its differences. These were regions with distinct cultural identities and languages as varied as Tulu, Konkani, Kodava Takk, Urdu, Marathi, Telugu, Tamil, inter alia. Veerappa further documents a "Namma Rajyotsava" programme, a televised event to mark the birth of a unified Karnataka state, where the question, “What is Karnataka’s original name?” is posed. “Mysore State,” comes the answer from a man named Abdul Razzak, and much is made about a Muslim man knowing the answer to a ‘Kannada’ question, which certainly would not have been the case if a native Hindu Tulu speaker provided the same answer.

The statewide despondency at Nag’s early passing in 1990 bears many resemblances to the recent untimely death of actor, singer and film producer Puneeth Rajkumar, a custodian of Kannadiga culture, much like his father Dr. Rajkumar before him. Walking back home on the day of his passing through a neighbourhood largely populated by Tamilians, I caught a small exchange between two Tamil men:

“What happened?”

“That boy died, Rajkumar’s boy.”

“Who?”

The following day, a few flex banners were erected in Puneeth Rajkumar’s memory at the site of the previous evening’s gupshup. One of the more enduring images of the Gokak agitation in the 1980s that fought for the first-language status of Kannada in the state of Karnataka is that of Dr. Rajkumar flanked by Nag, during a rally in favour of the rights of native Kannadigas. The successful mass movement gave rise to many ethnonationalist impulses in the decades to come, be it the anti-Tamil violence that simmered through the 1990s and 2000s or the absurd anti-Urdu riots of 1994 that stemmed from a public broadcast of prime-time news in Urdu on the national broadcaster Doordarshan. In the present day, ethnonationalist outfits like the Karnataka Rakshana Vedike are a far more diminished force, often lacking the critical mass to bring cities to a standstill as they once did. If Shankar Nag "Comes Asking" once more, one wonders where he would even begin.

To read more about the evolution of cinema in Karnataka, please click here.