Selar Sabu of Mysore: Revisiting the Elephant Boy

Mysore-born actor Selar Sabu’s foray into Hollywood represented a phase of primitivist oriental obsessions. Born in 1924 on the banks of the Kabini river into a family of mahouts of the erstwhile Mysore kingdom, Sabu arrived in the West on the same figurative ship that brought stories of Tarzan and King Kong. While in the West, Sabu starred in adventure films like The Thief of Bagdad (1940) and The Jungle Book (1942), both directed by Hungarian-born filmmaker Zoltan Korda; Arabian Nights (1942); White Savage (1943); and Cobra Woman (1944). "Sabu Dastagir", as he was often credited in films, caught the attention of British filmmaker Michael Powell, who said there was a “grace” about him and cast him in the Powell and Pressburger classic Black Narcissus (1947). Sabu also served in the Second World War and married Marilyn Cooper, a little-known actress, settling for a quiet suburban life in the San Fernando Valley in California before his sudden demise due to cardiac complications at the age of 39.

copy2.jpg)

Selar Sabu in Zoltan Korda's film The Jungle Book (1942).

To most people living in India, Sabu’s story would presage the modern flight of Indians to other countries, though Sabu’s own times might have made his trajectory rather exceptional. The photographer TS Satyan writes of his early memories of Sabu in his memoir Alive and Clicking (2005):

“With his gleaming white teeth, smooth coffee-brown skin and flowing black hair, he moved nimbly from elephant to elephant whispering sweetly into their ears. The elephant boy looked like a charming prince, waving his hands in the air while greeting the small crowd that had gathered to see him. A few days later I read in the newspapers that the white man who had come to Mysore was a cameraman and a representative of Alexander Korda, a well-known film producer in London. He was so charmed by Sabu that he had convinced the mahouts to let him act in Elephant Boy, a film Korda was producing. I witnessed the film shooting in the jungles near Mysore. Elephant Boy was a hit in the city and was screened for a month at Chamundeshwari Talkies.”

While modern notions of a mahout might evoke an older, even feudal order in places like Kerala, Sabu’s prominence as a mahout owes, in great part, to the very hypermodern visions of the Dasara Exhibition conducted by the Mysore Wodeyars in the early part of the twentieth-century, wherein the elephant procession played a pivotal role. Till date, the exhibition remains a prominent fixture in Mysore’s cultural calendar and continues to be an occasion for the Wodeyar crown to transcend their purely ceremonial title in post-colonial India. Historian Janaki Nair compared the exhibition—which commenced in 1907— to Wembley, and it still attracts tourists from across the state and country:

“As a triumphant metaphor of industrial strength and imperial power, the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924 exerted extraordinary influence on the minds of the bureaucrats of Princely Mysore, who were obsessed with the idea of bringing a ‘national’ economy into being. The Mysore Dasara Exhibition, first held in 1888, then revived in the early twentieth century as an annual affair, with only a brief break, was envisaged, quite rightly, as a spectacle and an education, for what may have been amusement for the elite Indian or British visitor, but was indeed intended as an instruction for the masses…the quantum leap elsewhere in the scale and frequency of such exhibitions has been understood as the epitome of bourgeois consumerism, a show of mercantile power, or even an ‘imperial archive’. Yet, in India generally, the prospects of large-scale industrialization or economic transformation under colonialism were slight, until the slow growth of ‘development’' discourse in the interwar period, when nationalist pressure, the imperatives of wartime production, and the need for renewing the legitimacy of imperialism led to the thawing of rigidly imperial objectives. In Mysore, particularly in the interwar period, exhibitions became a crucial site for imagining a new economy.”

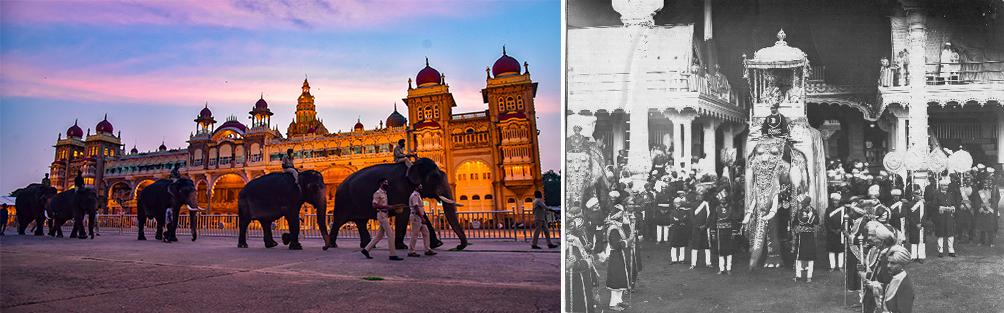

Left: Elephants preparing for the 2018 Mysore Dasara. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Right: The Mysore Dasara parade in the colonial era. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Mysore of Sabu’s youth was a curious mix of the old world represented by the courtly culture of the Wodeyars and the radically new secular labour market (premised on uninherited labour), ushered in almost overnight by the British Raj, in the wake of the Subsidiary Alliance that essentially subordinated a vast majority of the former princely states of the subcontinent. These developments are borne out in the words of the arch-modernist Dewan (Minister) of Mysore, Sir Mirza Ismail: “Mysoreans wash themselves with Mysore soap, dry themselves with Mysore towels, clothe themselves in Mysore silks, ride Mysore horses, eat the abundant Mysore food, drink Mysore coffee with Mysore sugar, equip their houses with Mysore furniture, light them with Mysore lamps and write their letters on Mysore paper”. At the time, Mysore was also emerging as a prominent producer for steel, cement, chemicals and fertilisers, aircraft, glass, porcelain, agricultural implements and cast-iron pipes, with only fragments of this past carrying on to the modern deindustrialising Mysore. It was thus that Sabu, the "elephant boy", was the product of two distinct modernities and not just a beneficiary of one that "saved" him from the aane karoti of the kingdom of Mysore.

. png.jpg)

Italian film directos Vittorio De Sica and Gianni Franciolini with Sabu in Roma. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

To read more about the evolution of cinema in Karnataka, please click here.