The Roles We Play: Sifting through the Familial in Shared Solitude

The social significance of the idea of family lies in the celebration of attachment which embeds the family in an intricate web of sociality, authority, convivium and personhood. It is through this act that the family is narrativised—fleshed out by an attention to detail and the dominance of a gaze that is definitive and unrelenting in visualising coherence and order. Shared Solitude is a series of family portraits made by Anita Khemka, in collaboration with her partner Imran Kokiloo, conceptualised and photographed during the lockdown of 2020 at the height of the coronavirus pandemic. Isolated during the COVID crisis, coupled with a set of family emergencies, Khemka and Kokiloo were moved to wonder about what constitutes the familial, the ways it comes into being and, more often than not, how it remains a conjured reiteration of belonging. As a contemplative experiment with portraiture and studio photography, partly introspective and partly dissipatory, Shared Solitude provides a multi-faceted definition of the familial, unafraid to take certain liberties in unfolding the same.

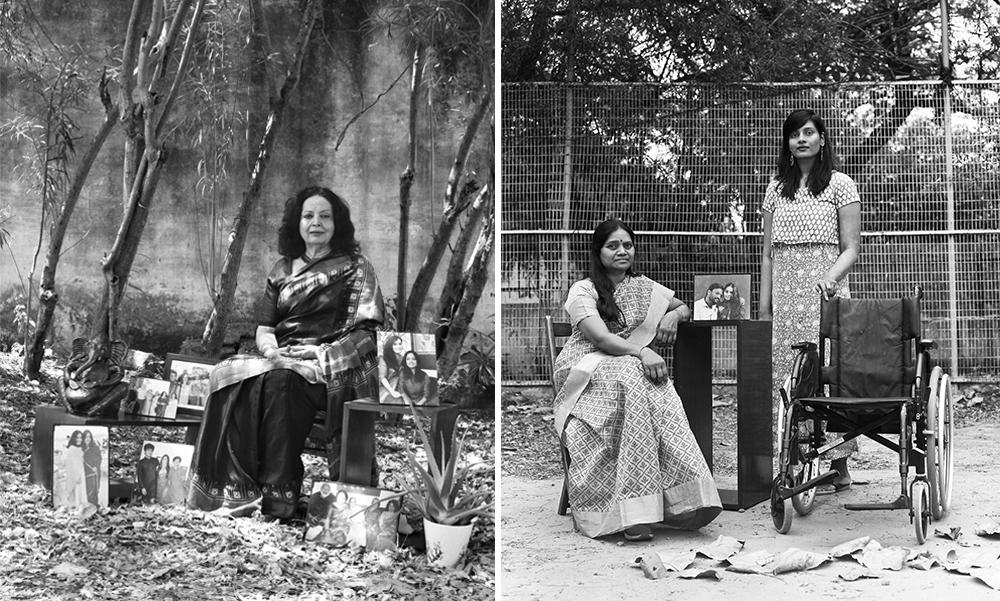

Left: Untitled VII

Right: Untitled VIII

Due to the exigencies of the pandemic and its restrictions on movement, early portraits from the series were made in parks—part of the artists’ residential neighbourhood—establishing a studio setting ushered out of its usual formal context. Speaking to a few of their neighbours and friends, the series began to take shape through conversation and a shared inclination to gather. With a couple of wooden chairs and boxes, the outdoor studio setting that emerged was one that enabled the mapping of their sitters, not simply by their faces but also by the things that they could bring with them. In an interview with Critical Collective, Khemka and Kokiloo reflected upon the participatory nature of the process of making these portraits, where they invited their sitters to work with them in conceiving and conceptualising an “open and neutral space.”

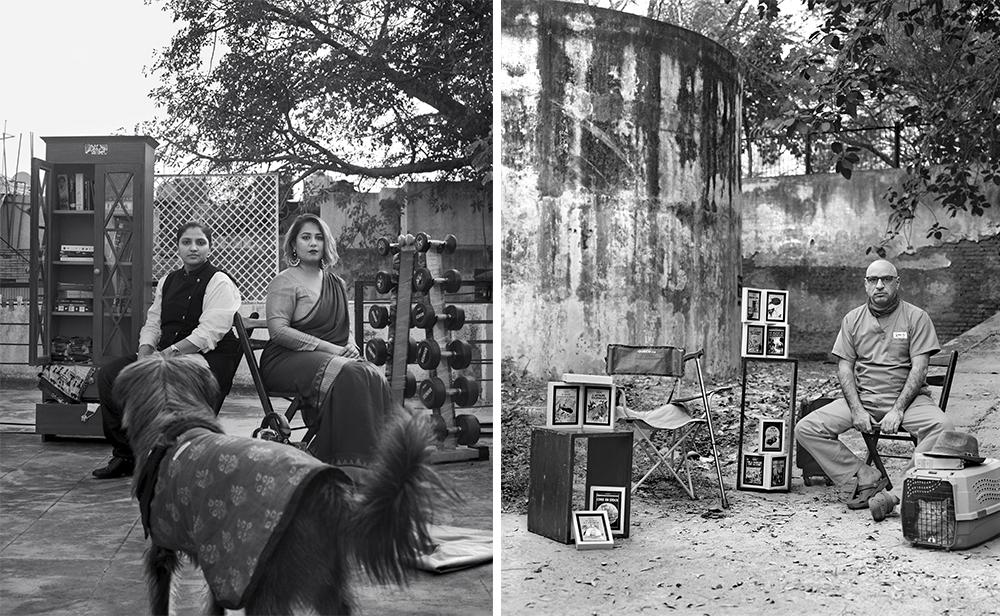

Left: Untitled XXVI

Right: Untitled XXXIII

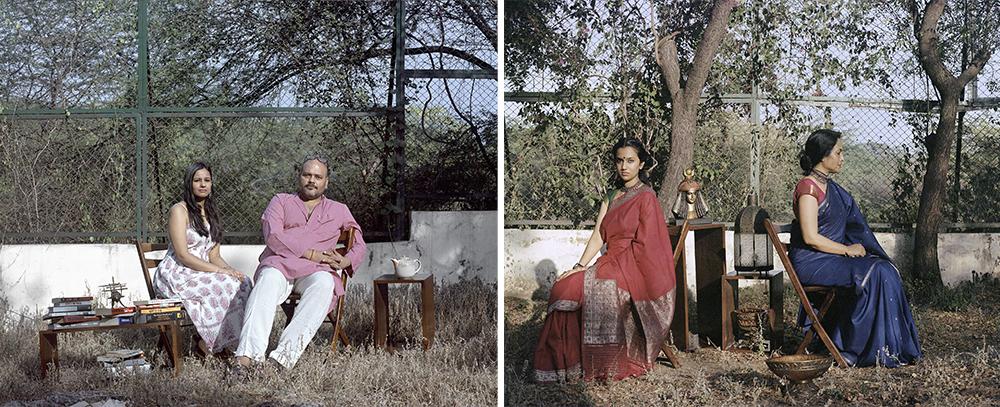

Sitters were encouraged to bring objects, curios, material remnants, residues and anything that brought to life an idea of the family for them, emphasising a texture of the domestic space as something increasingly relational and easily re-sited. Shot on expired film, the portraits also entail a slowing down of the image-making process. This made for a complex collaboration and extended the familial to a spatio-temporal zone beyond individuality, into forms of attachments and interior landscapes represented by the sitters’ objects as well as the processes they constituted. Finally, what remained evident was the underlying significance attributed to the ceremony of making each portrait; with each reading that one proffers, the photographs reveal a shared trust and profundity, a symbiosis of careful thought permeating an incredibly private iteration of the familial in a public space.

Left: Untitled XXXIV

Right: Untitled XXXV

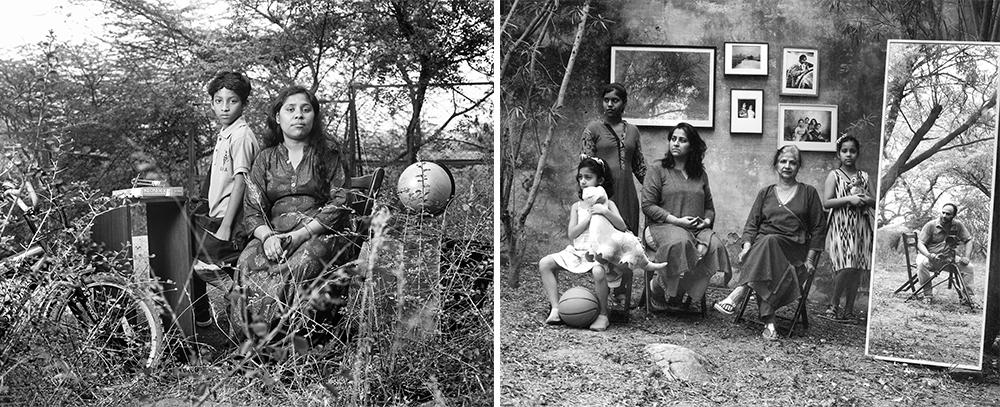

Memory, loss and nostalgia appear as critical thematic elements in several of these family portraits. These themes are particularly embodied by the objects surrounding the sitters such as the other framed photographs within the studios set up for each family, representing late loved ones, shared memories and other instances of the familial. This lends to the fascinating essence of the photographic medium and its association with remembrance. In the series, the domestic appears as one that is both carrying and is being carried by the family portrait, which performs and elicits a critical proximity with a relational space essential to the domestic.

Left: Untitled XI

Right: Untitled XIV

There is a discursive nearness re-enacted between the sitters and their chosen objects apart from the usual clasped or folded hands, limbs resting against corners and shoulders, a hand grasping the grip of a wheelchair of a missing father and another sliding shyly into a bag. The books, the odd teapot, play sets, a cat in a carrier, the occasional souvenir, a bust or a trinket are apposed with the weight of familiarity and reassurance, one that constantly shifts between the subjects and their objects as well as the photographer and photographed. In Khemka and Kokiloo’s own family portrait, their daughters firmly hold onto toys and Kokiloo’s hand calmly guides the camera towards the frame. What does it mean to co-witness the familial as it takes shape?

These portraits can be read as an act of coming together, running parallel to ideas of belonging and togetherness, performed with a faith in posterity. Within the public setting of a nondescript park, continually redefined by chosen curios, the notion of familiality—the quality of being familial—is instituted, among other things, through the afterlives of certain objecthoods. As a corollary, the "object" actually being instituted in turn, over and over again through these images is the idea of the family itself. As an ongoing project, Shared Solitude will continue to unfold, reading and tracing shifting interpretations of the familial. It takes seriously the signs and symbols people make and choose to represent themselves; it tells of how the portrait is self-historical in the way that it produces narratives outside the binary of truth and fiction, and the domestic emerges as an improper elongation, pulled in different directions, in a time of unprecedented isolation.

All photographs from Shared Solitude by Anita Khemka and Imran Kokiloo / PHOTOINK. 2020. Images courtesy of the artists.