Virtual Memories: On Suneil Sanzgiri's Letter From Your Far-off Country

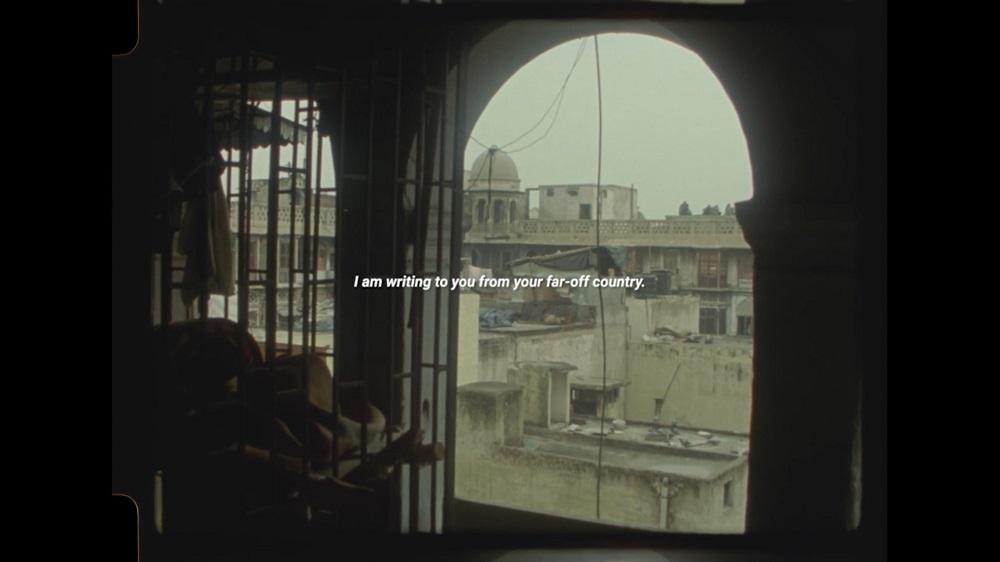

Suneil Sanzgiri’s experimental film essay Letter From Your Far-off Country, assumes the shape of an epistolary meditation and dialogue on the growing threats to Indian democracy over the last few years, and its threatening attempts to eclipse the radical pasts of the country. Employing a familiar mode of exilic longing for the radical space of home in a cosmopolitan imagination, Sanzgiri’s film gathers a string of images burrowing into the histories of oppression and injustice suffered in the country by radical reformers and activists of the Communist Party of India’s cultural organs, the remarkable voices of insurgent students in the country, and the dangerously manipulable legacy of Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar. If exile has traditionally suggested the ways in which the Indian diaspora loses touch with their sense of home in a far-off country, this film explores the manner in which a country too can drift away from one’s sense of self and history. Even if the protests and injustices seem to multiply closer to our time, Sanzgiri’s film reminds us about their pervasive roots forming the subcontinent’s memory of violence and trauma.

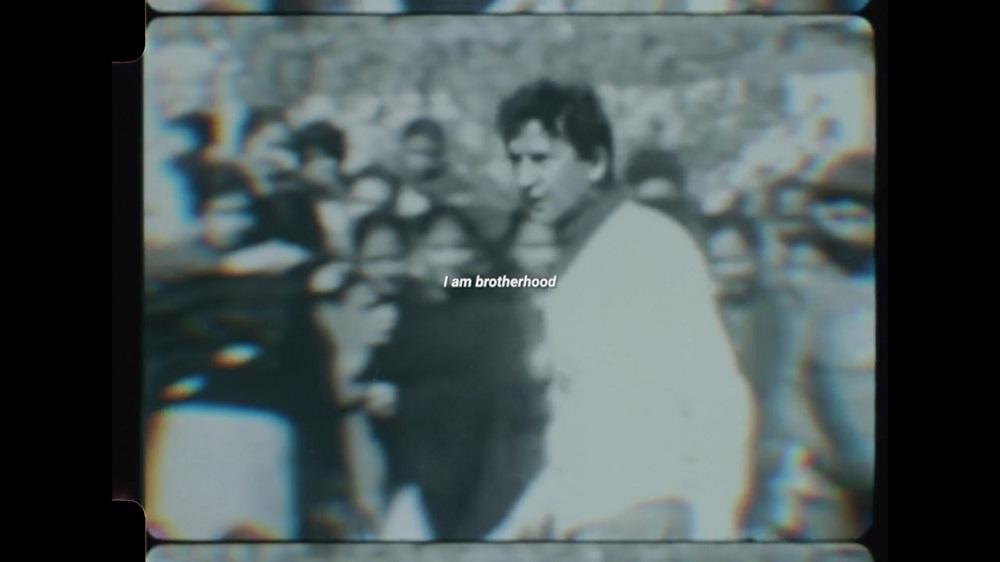

Rare footage of Safdar Hashmi performing in the streets. Image courtesy of Sanzgiri from the Jana Natya Manch—Hashmi’s street theatre troupe.

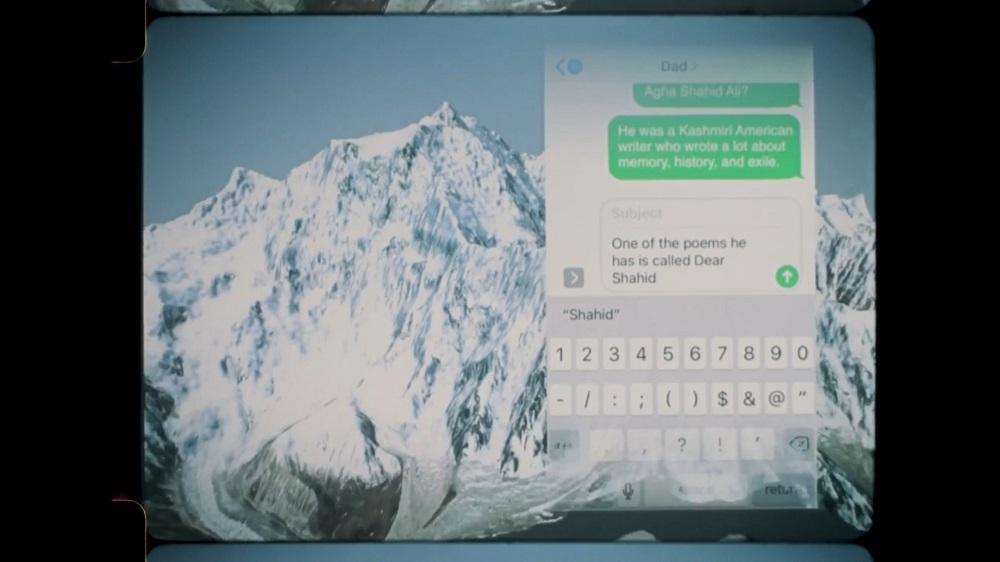

The film opens with Sanzgiri meditating on the etymology of his family name, digitally rendering the shape of mountains ("-giri" meaning mountains, from which his name derives in Konkani) in Kashmir—an imaginary space that has become the site of contestation over individual memory and state repression. He recovers a resonant reading of Agha Shahid Ali’s letter-poem “Dear Shahid”, recited by a student of Jamia Milia University, which struggles to make sense of the brutal history of the land for an exiled poet. Sanzgiri’s personal distance from the country of his origin parallels the poet’s own sense of longing for a geographic space that is transformed imaginatively into a map for the future, where a new beginning can be forged.

Sanzigiri recovers the memory of events and people, trying to work out how those politically transformative pasts have led to such a precarious present—a present marked by the women-led protests at Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which is blatantly meant to dissolve the egalitarian legacy of Ambedkar’s constitutional dreams for a new India. Ambedkar’s image has become a pliable, plastic object in the hands of modern politicians who are using his legacy to whitewash their own agenda, as implied by the filmmaker. He resurrects the memory of his distant-relative Prabhakar Sanzgiri, who was a Communist leader in Maharashtra and wrote books attempting to forge a common ground between Marxists and Dalit-Ambedkarite politics. While this common ground has eluded radical politics in India, Sanzgiri’s logic of images serves as a reminder of the failures of this vision of emancipation.

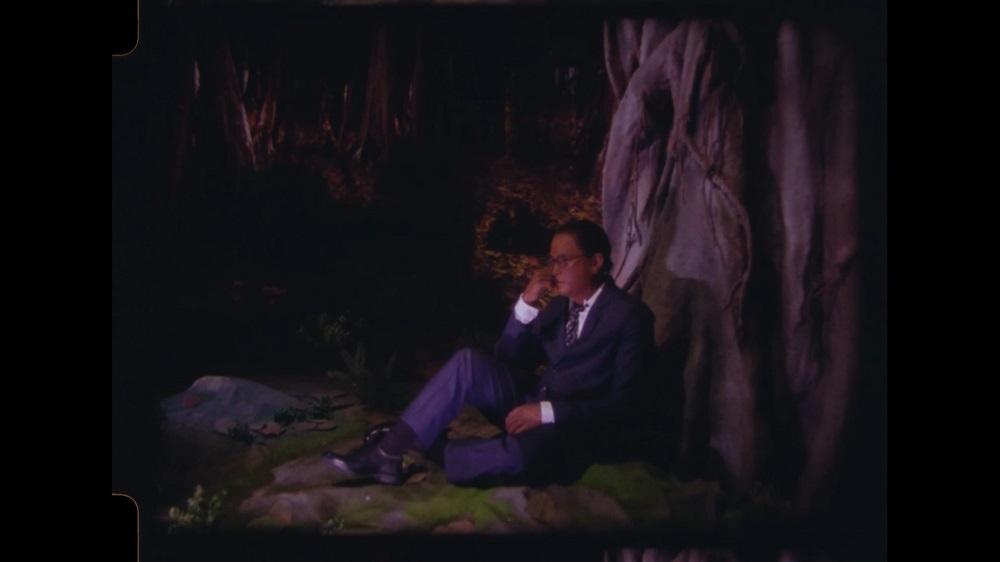

The film also highlights Indian cinema’s own radical past—a time when popular actors took difficult positions in public. Thus, this leads him to producing footage of the Indian “parallel” cinema actor Shabana Azmi’s famous public protest at the International Film Festival of India 1989, which took place the same year that Safdar Hashmi, a playwright, performer and member of the Communist Party of India (M), was assassinated by thugs hired by a Congress (I)-leader. The memory of Hashmi’s cultural and political war cry "Halla Bol” resonates through this gesture, down the years to modern day protest movements that use the same cry along with other weapons devised by poets and singers of the past, such as Faiz Ahmed Faiz who wrote Hum Dekhenge, which was put to song most memorably by Iqbal Bano in 1986.

Sanzgiri uses text, animation and multimedia images shot on 16mm film, or borrowed from rarely seen archives to construct this fragile new polity of a future built on solidarity. Although nostalgic in tone and affect, it builds on the wry and ironic tools of multimedia critique used by experimental filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard in films like Letter to Jane or Hail Sarajevo. Godard’s own famous disruption (along with other filmmakers) of the Cannes Film Festival in 1968, protesting on behalf of striking workers, served as an inspiration for Azmi’s later gesture. In employing a mix of styles, Sanzgiri suggests that these tools of image-making and remembering should be appropriated by artists and used for re-shaping old structures and constructing new grids of enquiry. Fittingly, Purnendu Pattrea’s words appear on screen:

“Assault is not a new word

Violence is not a new word

The new word is Safdar Hashmi

Safdar Hashmi means waking up

Staying awake

Awakening”

Therefore, through the work and vision of radical artists like Hashmi, the present can be infused with revolutionary longings, courage can be extended to besieged voices, and one can hope to prevent the foreclosure of a better imaginary future for Ambedkar’s republic.

All images from Letter From Your Far-off Country by Suneil Sanzgiri. 2020.