Photograph as a Commodity: Professional Photography in Twentieth-Century Calcutta

The practice of photography is not only derived from the photographic images themselves but is situated in multiple visual, cultural and social registers. Therefore, exploring the history of professional photography is embedded within networks of its production, circulation and reception.

Photography arrived in South Asia in 1840 within a year of its invention in Europe, leading to the opening of the earliest photographic studios in the Presidencies of Bombay and Calcutta. To trace the early history of photography in India, one must highlight the evolving phenomenon of the erstwhile colonial subject trying to master a decidedly European technological import and understand its socio-cultural and aesthetic implications on the visual worlds and lives of the people. As the modern technology of photography entered the social and cultural worlds of what we now know as India, the city of Calcutta fast became one of the firsts to accommodate the camera into its public life. Calcutta, much like the other Presidency cities, contained a number of British-owned photographic studios as the camera ventured into late nineteenth-century India. These British-owned studios would have Bengalis of various professional levels working there, but by the beginning of the twentieth-century, the city of Calcutta had a small but considerable number of successful Bengali-owned studios.

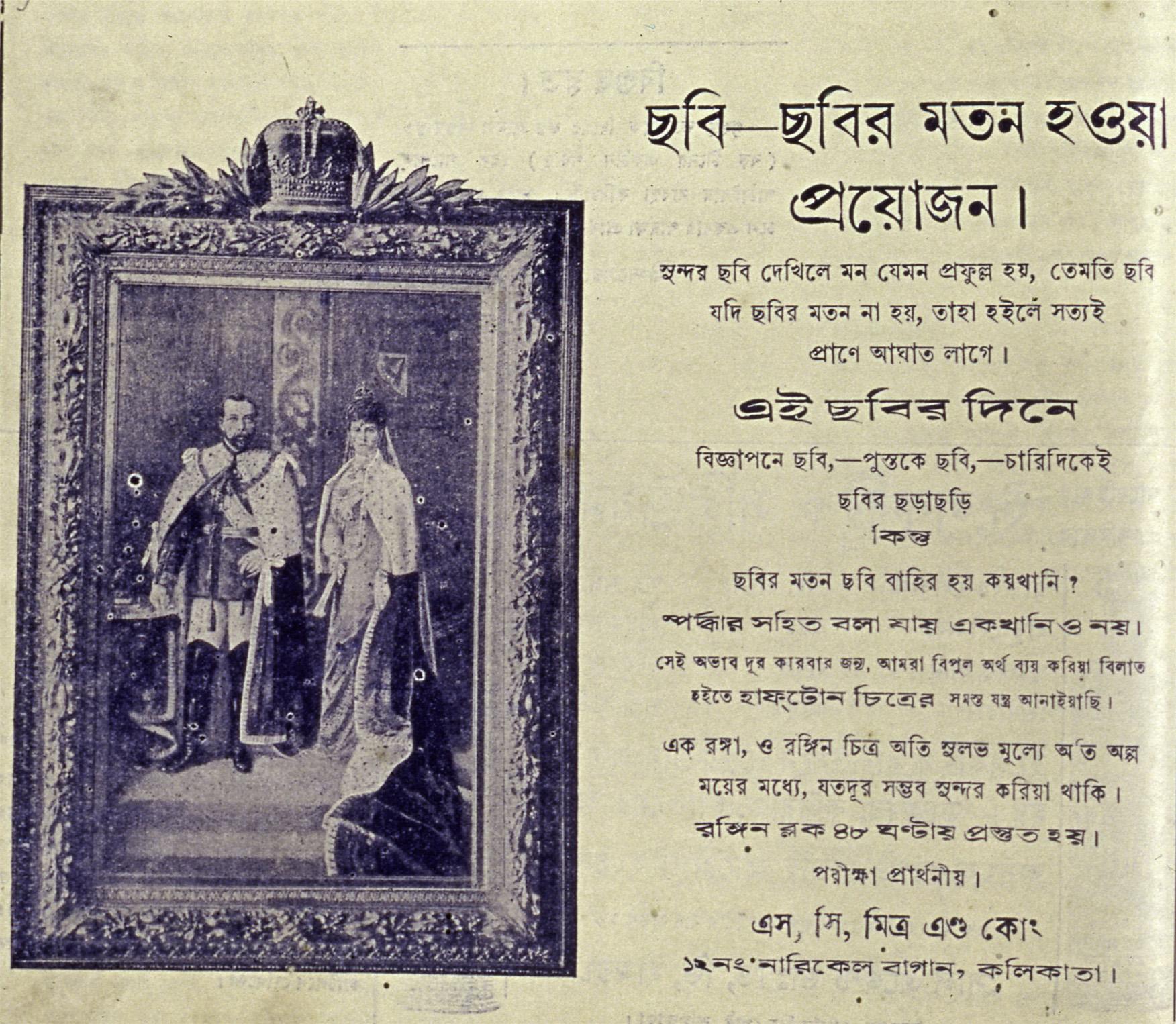

Advertisement of S.C. Mitra & Co., Calcutta, titled “Chhobi—Chhobir Moton Howa Proyojon” (a photograph should be picturesque) published in the journal Prabahini, 1320 BS (1913).

Advertisement of S.C. Mitra & Co., Calcutta, published in Prabahini, Chaitra 13, 1320 BS (1913).

With the advent of new printing techniques such as lithography, chromolithography and oleography in the late nineteenth-century, there was a rapid proliferation of mechanically reproduced and widely circulating visual images targeted towards public consumption. Advertising was one such arm of the new visual print genres, which ensured publicity and popularization of their products and services through their circulation in the market. It provided a new language that helped shaped consumer culture.

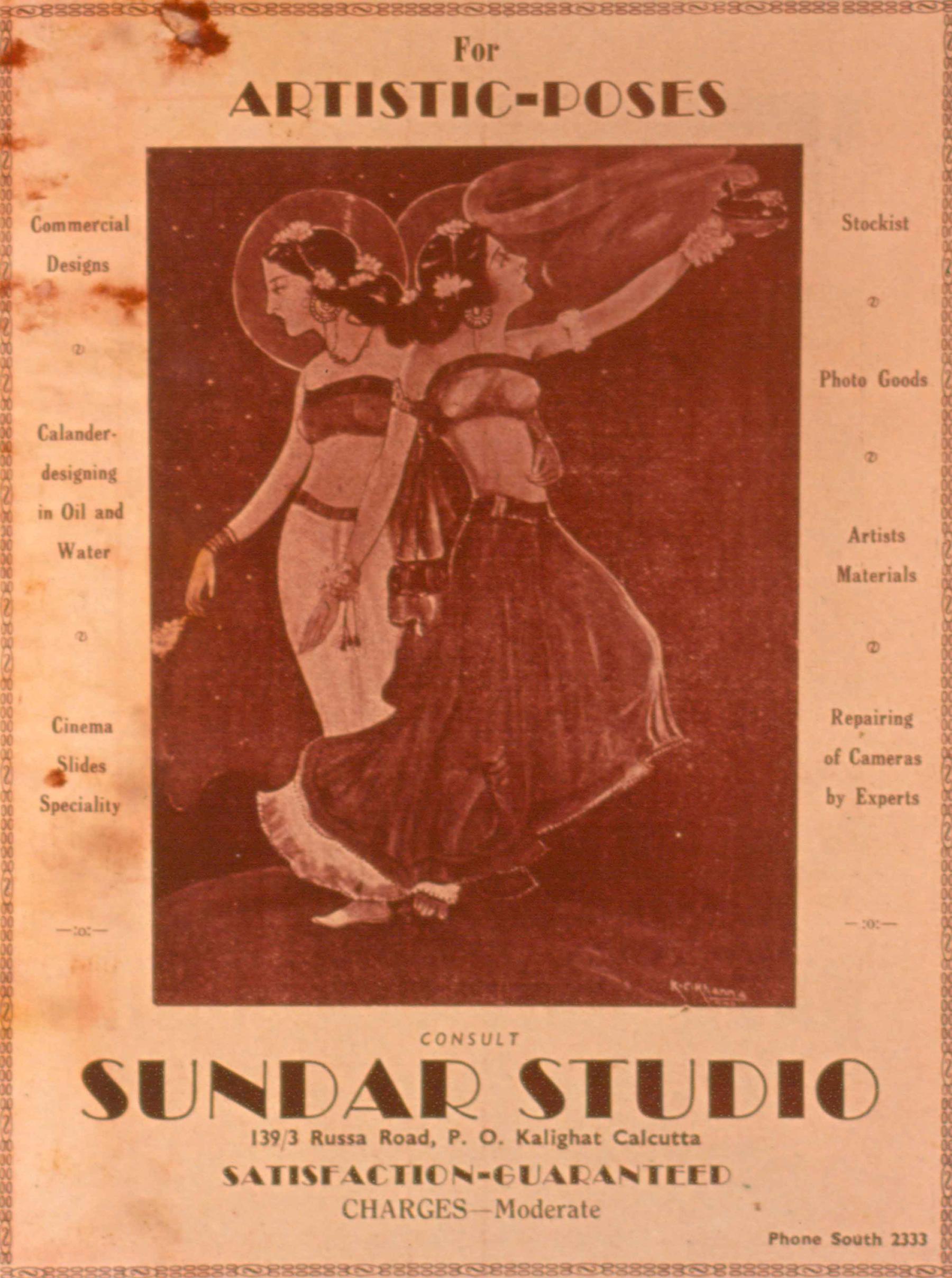

Advertisement of Sundar Studio, Calcutta, published in Fine Arts Souvenir of All India Exhibition 1948 in Eden Gardens Calcutta, 1948.

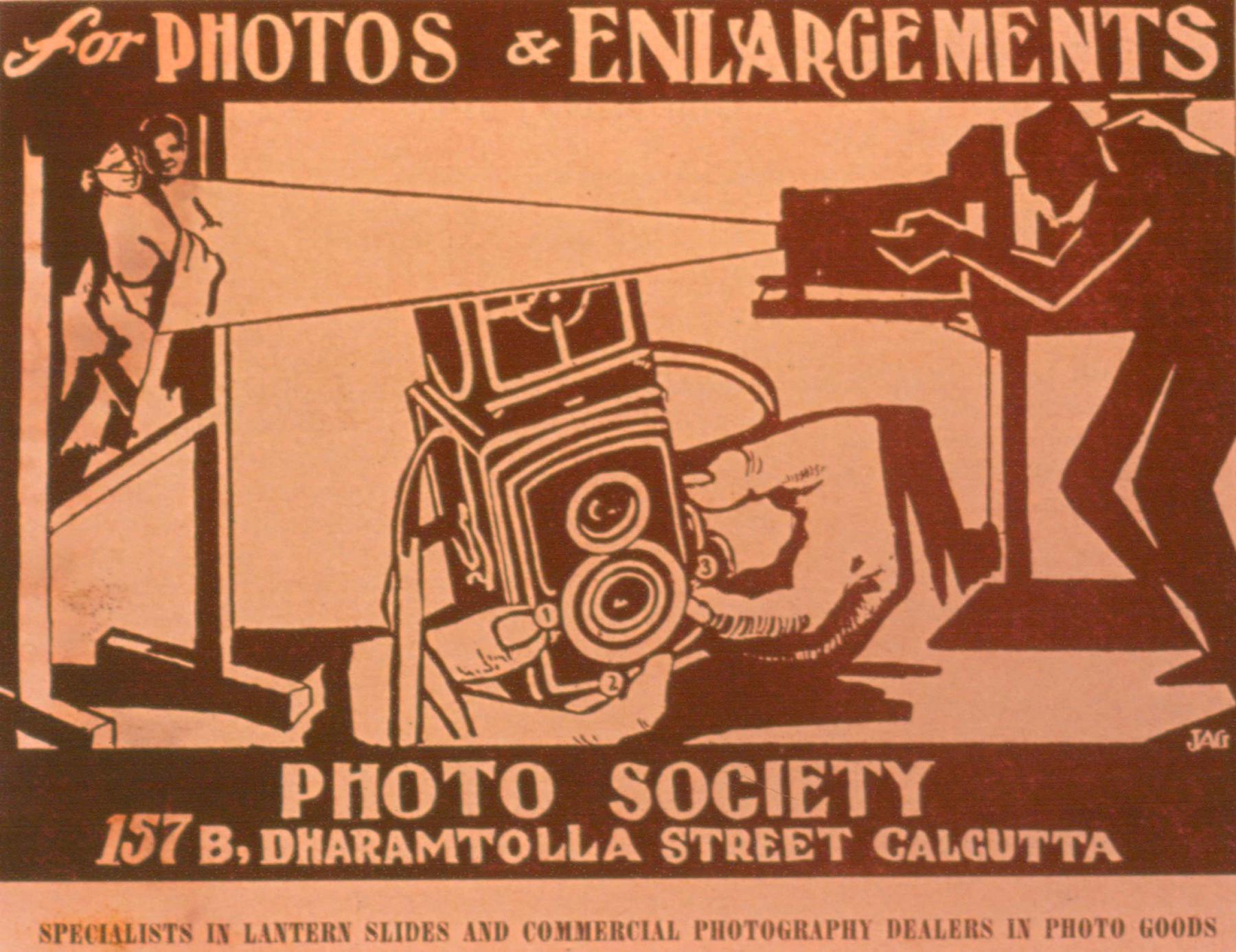

Advertisement of Photo Society Studio, Calcutta, published in Fine Arts Souvenir of All India Exhibition 1948 in Eden Gardens Calcutta, 1948.

In the twentieth-century, the flourishing advertising industry aided professional studios in promoting their business. Erstwhile, the photographer–client relationship depended more on informal networks and physical proximity. However, with the advent of an advertising culture, it was possible for a studio to reach a wider audience through the print medium of newspapers, journals and periodicals. Many of the British-owned and Bengali-owned studios started advertising themselves to approach untapped markets. These advertisements highlighted the uniqueness of their craft, sometimes endorsing their cutting-edge photographic equipment and masterful technicians and at others trying to ignite nationalistic fervour by inviting clients to indigenous, locally-owned studios.

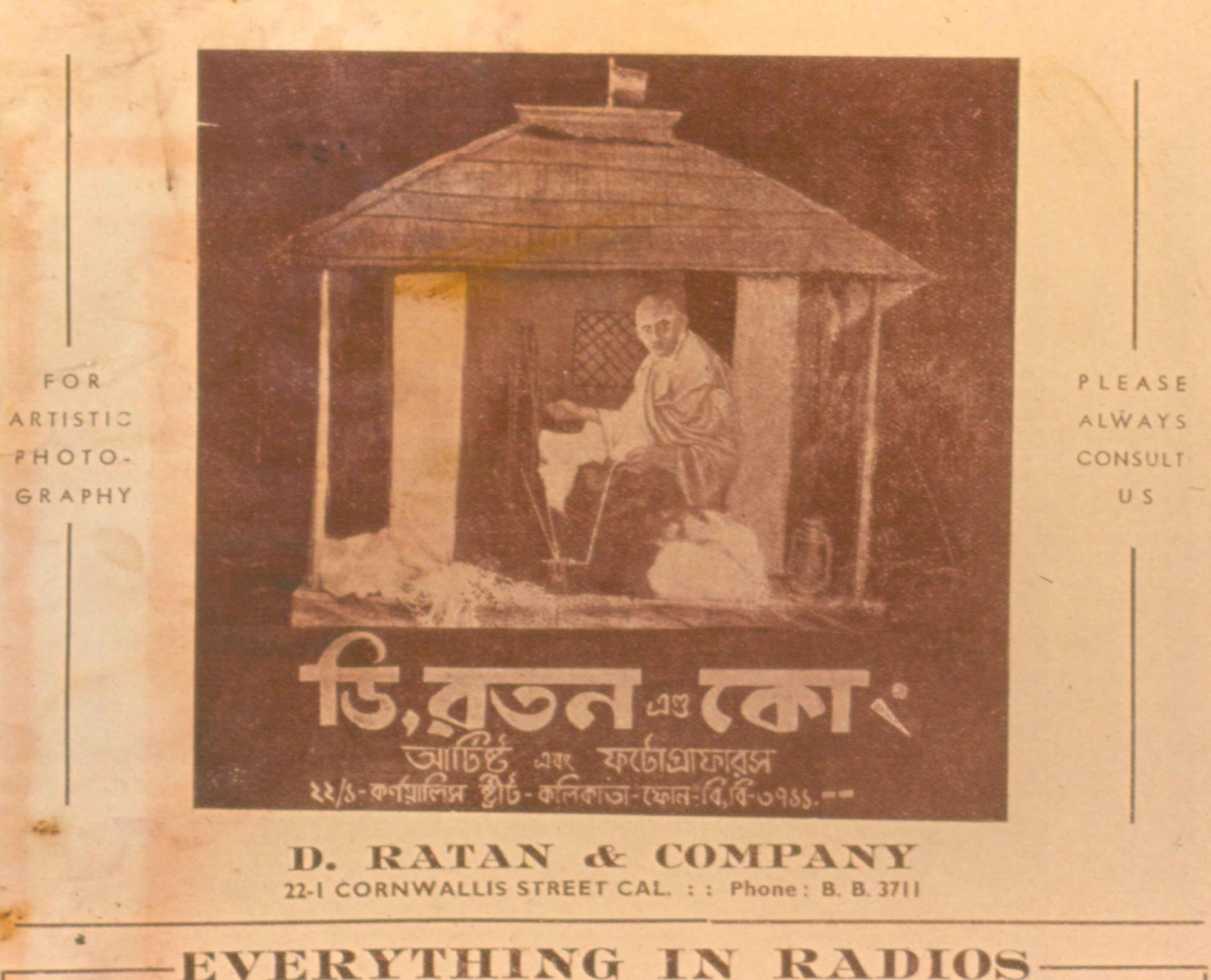

Advertisement of D. Ratan & Co., Calcutta, published in Advertisement from Art in Industry, Volume 1, No. 1, 1948.

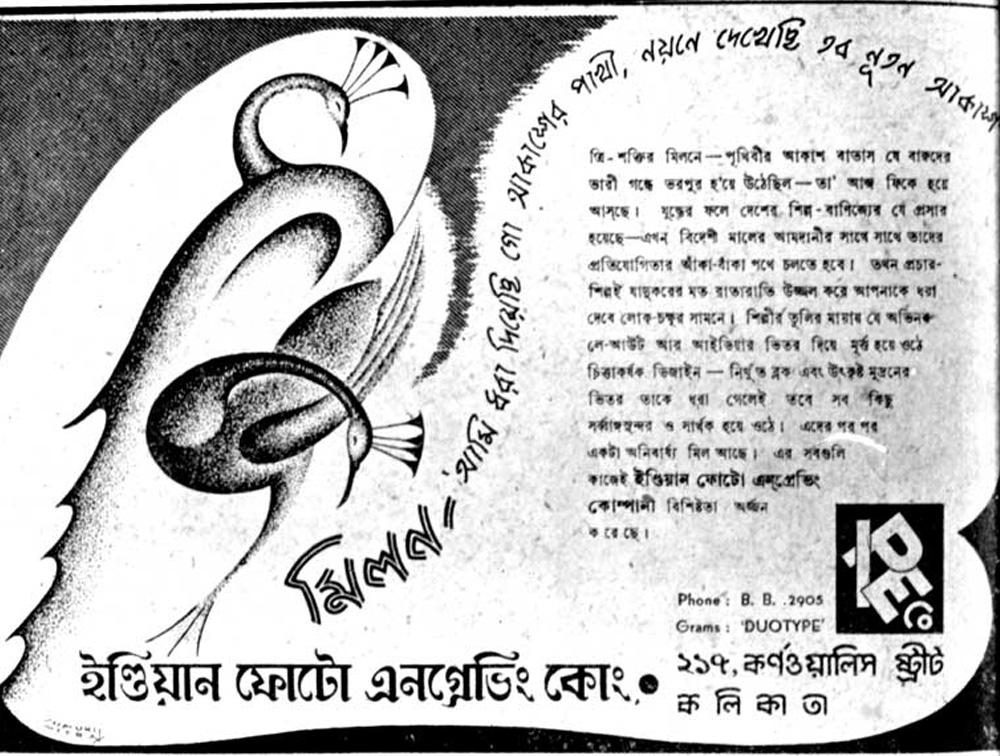

Advertisement of Indian Photo Engraving Company, Calcutta, published in Sharadiya Anandabazar Patrika, 1945.

A history of photography as a profession in twentieth-century Calcutta can be traced through these images. Additionally, these advertisements often illuminate the contemporary aesthetic conventions and cultural norms intricately woven into the photographic practice.

All archival images belong to the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta.