Amorar Akhyan: Dilara Begum Jolly’s Tales of the Undead

Dilara Begum Jolly is one of Bangladesh’s most essential critical voices in contemporary art, with a practice stretching across painting and drawing to multimedia work with videos, textiles and print. Some of the regular themes in her work address the complex legacies of women’s history in Bangladesh, especially their public roles and sacrifices at the time of the violent Liberation Struggle of 1971, which resulted in the independence of Bangladesh. The many sides of her practice are usually on display in her shows, such as in Threads of Testimony which sought to foreground the experience of women working in Dhaka’s garment districts. The country’s clothing industry is often viewed through an exotic lens of exploitation and tragedy, especially following the Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013. Thus, Jolly’s work has tried to re-work this singular one-sided gaze into a richer, more patterned way of seeing tragedies of the sort that implicate this life of labour in Bangladesh presently. Many of these concerns come together in her video installation The Departed Soul, or Deher Akhyan (The Tale of the Body), which was shown alongside other works for her exhibition, such as Amorar Akhyan (Tales of the Undead).

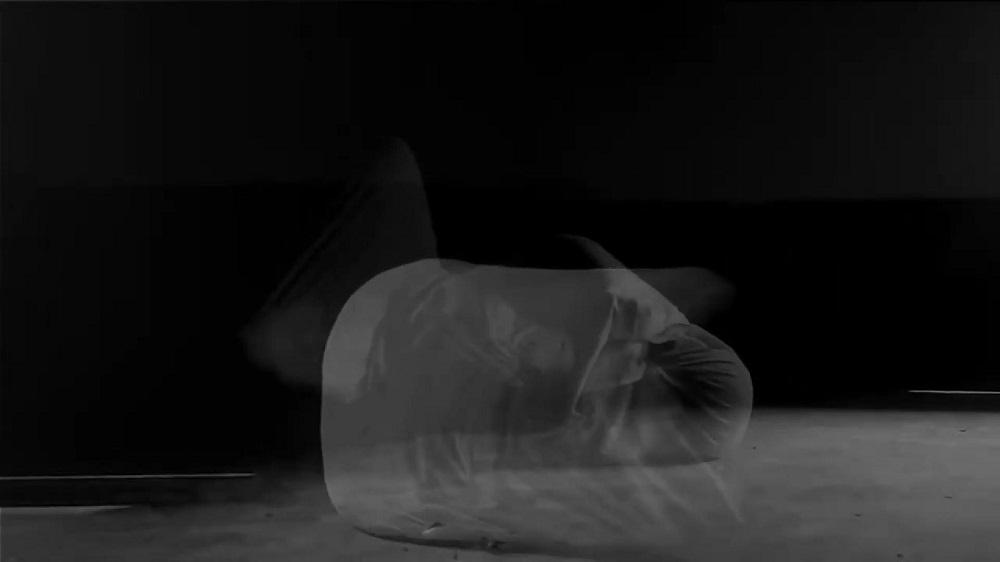

The film lies at the cusp of performance and video art, where both forms are utilised to arrive at a more poetic rendering of a haunted space in national memory. Situated within the confines of Mahamaya Dalim Bhaban in Chittagong, which was converted into a temporary cell for torturing dissidents during the Liberation Struggle, the site evokes no ordinary haunting as it peels apart the layers of significance surrounding the complex interactions between fabric histories, women’s bodies employed as tools of national construction and the womb-like presence of the dark and violent space that gave birth to new subjects. As a critical citizen of the country, no one can escape the conflicted legacies of such a violent creation myth, especially one that so explicitly constrained women’s bodies. The white sheet of clothing furled around the enigmatic body, assumes the tensile strength of these questions. Jolly identifies the difficult inheritance of the space, which now wears a dilapidated look, when she writes, “It was there, in the hollow, vacant apartment that I was led to chart a new cartography of their past. It was there, in the array of echoing voids that I was enveloped in a whispered dialogue with their previous reality. It was there that a murmuration of spectral images, human, physical, spoke to me of another creation-story for the present.” The haunted house is rendered a shrine, lodged in the heart of a dark and hollow cave.

While the fabric appears to shrink-wrap and anonymise the human subject, it also allows the subject to assume phantasmic shapes and forms, such as hardening around the window grilles to suggest the shape of a hand, or becoming smoke-like while spilling out of a vent. As fantasies of a pliable body that cannot be fully grasped, they provoke us to confront the ways in which countless nameless bodies were forced to adapt themselves to the demands of a new sacred idiom for a new nation. For what nurtures, gives birth and aids creation can also inflict violence, loss and trauma carried across generations, borne by the skin and reflected in every twist of fabric.

All images from Amorar Akhyan by Dilara Begum Jolly. 2015. Courtesy of the artist.