The Beast Named Development: Shishir Jha’s Dharti Latar Re Horo

“It is difficult to tell what is the truth and what is myth.”

Dharti Latar Re Horo (Tortoise Under the Earth, 2022), directed by Shishir Jha, explores the tale of an adivasi family who have lost their daughter in the uranium mines in Jharkhand. While the film centrally portrays this story of an individual, personal loss; it opens up a piercing window into the interconnected ecological and social transformation of the community life of the Santhals, the traditional custodians of the mining area.

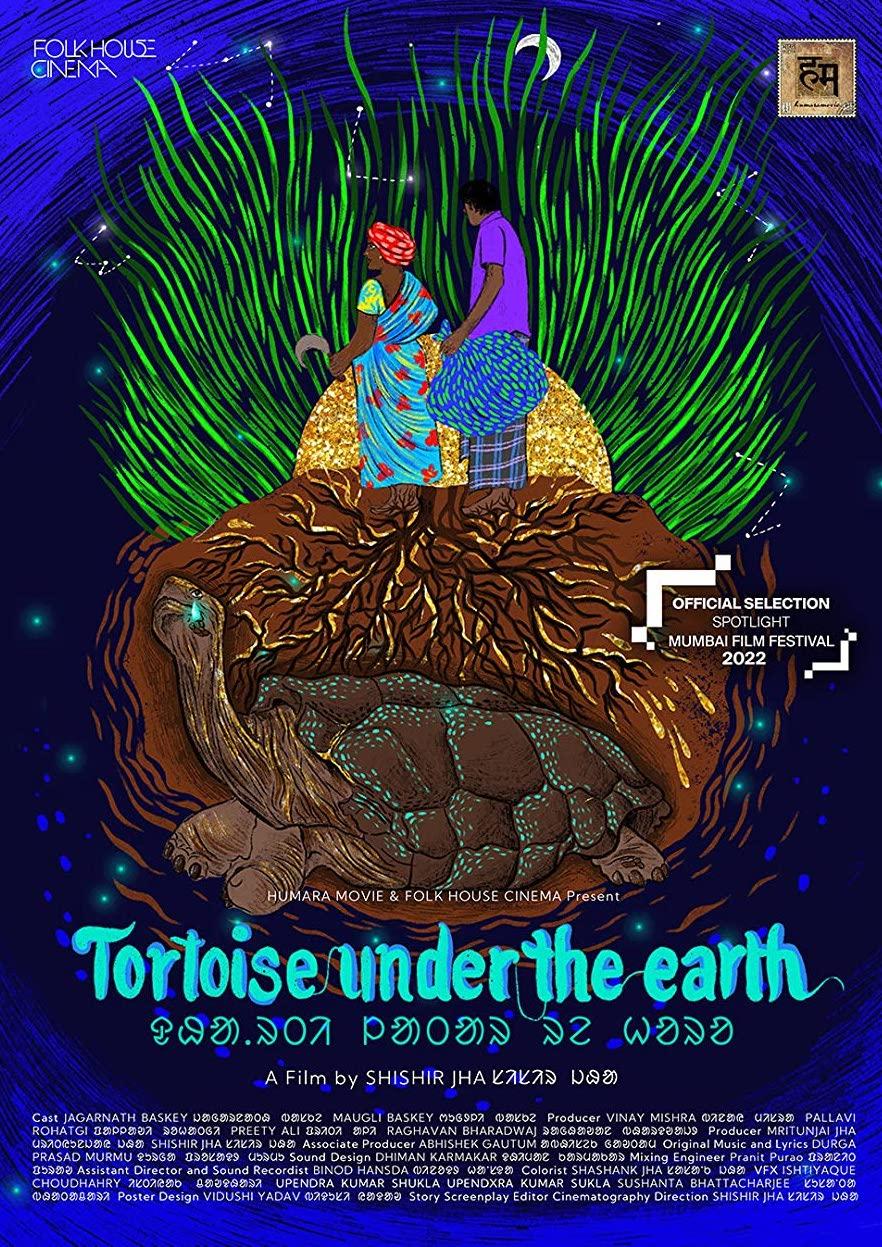

Official poster of Dharti Latar Re Horo. (Dir. Shishir Jha. 2022.)

The contested idea of ‘development’ in independent India has historically been synonymous with large scale industrial expansion enforced by a government-corporate nexus. In a country marred by deep inequalities among caste, class, ethnicities, etc., such expansions have customarily been concentrated in areas inhabited by the most deprived sections of people. This further results in their lack of access to adequate resources or political representation to contest this paradigm of enforced development. Their stories remain peripheral to the dominant narratives of the nation state’s civilisational progress and economic growth. Jha’s cinematic tale is an attempt to capture this unequal daily battle imposed on people who remain physically remote from the cosmopolitan, urban centres of power. It captures people in their interaction with various natural surroundings, to depict the innate bond between nature and its inhabitants. As the camerawork focuses on vast expanses of nature, the film forces a conversation about a reality of land acquisition that is overshadowed by the exuberant celebration of advancement.

In the beginning of the film, a voiceover tells us a strange tale of the haunted banyan tree just outside the village. We learn that many witch-doctors, occultists, and religious gurus have tried to explain why the tree is haunted, as have many scientists from outside the village. While some say many women suspected of being witches have been killed there, causing the banyan tree to change its shape; the scientists have credited the transfiguration of the tree to the radiation from the nearby uranium mines. The haunted tree stands at the complex cusp between fiction and fact. It references the plight of the village, which has had to bear the cost of unrestrained, unsustainable development schemes—the planning and execution of which the local adivasi communities had no say. Here, the uranium becomes the real ghost—a not-so-absent presence subsuming those alive in the village and slowly causing decay and death.

Much like the transmuting presence of the banyan tree, Dharti Latar Re Horo exists on the borders between documentary and fiction. Following a Santhal couple, played by Jagarnath and Mugli Baskey, who lost their daughter in the uranium mines nearby, the film also captures the very conditions that enabled the possibility of such events. The particular cinematic language of the docu-drama form allows the viewers to witness the deep sense of displacement, loss and alienation that underwrites the lives and livelihoods of the Santhal community. By using snippets of news on a transistor radio and television, shots of activism and resistance, as well as expansive frames of the industrial sites and their ruins, Jha juxtaposes the contemporary situation with the everyday life of the couple and the Santhal community. We get to view the love between the couple while they attempt to cope with the distress of their daughter’s absence and the impending fate of their displacement from their homes. The loss of the daughter forces the mother into a state of despair where she keeps looking at photo-albums. Her inability to participate in the seasonal regime of harvest makes her husband worry about their starvation. With minimal dialogue, the film illustrates their easy participation in the surrounding flora and fauna, which still nurtures the memories of their happy days even as it reluctantly transforms due to industrial incursions.

The film captures how intrinsically the communities in the mining area are connected to their habitus—the land, forests, seasons, non-humans, and humans alike. It chronicles the numerous ways in which the beast called development unleashes its monstrosity—affecting the local economy, the cultural milieu, the resources of sustenance, and the familial and social bonds between people. Not only does this form of ‘progress’ change the natural surroundings to the point where they become inhospitable and poisonous, it also displaces people from their traditional homes and occupations while forcing them to migrate to the cities for work. It transforms the very bonds between lovers, families and friends, as everyone has to succumb to this overarching project. The mourning of the lost daughter is rooted in this backdrop. Here, the changing seasons are witness to the evolving repercussions of industrial development, and celebrations and mourning coexist in a way such that they cannot be separated from each other. Durga Prasad Murmu’s music demonstrates to us that there is no way to know whether the Koel bird sings in the month of phagun (spring season) to usher in the festivities of spring, or to declare its hunger pangs. As the community celebrates their seasons, there remain lingering effects of industrial expansion in all facets of their lives. The mother now sings of the lost daughter; the festival songs now reflect the undercurrent of hunger, destruction and estrangement. “How can I be at peace with all this turmoil?” asks the mother.

To learn more about Dharti Latar Re Horo, please click here.

To read more about the films screened at the 2022 edition of the Dharamshala International Film Festival, please click here, here, here and here.

All images from the film Dharti Latar Re Horo (2022) by Shishir Jha. Images courtesy of the director and Dharamshala International Film Festival.