Finding Archives Where There Are None: Documenting a Displaced Existence in the Forests of Chitwan

The “Anthropocene” is an idea popularised at the start of the millennium by the Dutch atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen to define a new geological era on Earth, one where the effects of human habitation are seen and felt in its natural systems—including but not limited to climate change. This idea has produced fertile ground within the field of humanities—towards an urgent consideration of both its immediate and remote futurity—in diverse disciplines such as anthropology, philosophy, art and activism.

A spectacle of modern technology opening a new frontier in Chitwan. A dozer clears the forest to pave way for the construction of infrastructure and an integrated economy. (Photograph by Dave Hohl. 1967.)

In The Skin of Chitwan, an online exhibition supported by the Nepal Picture Library (NPL), this notion becomes an agent in foregrounding the need for new readings and writings of history, including those that are often completely effaced in the state narratives of modernity and technological progress. The exhibition is a manifestation of the ongoing research project Indigenous Pasts, Sustainable Futures by NPL that attempts to document, archive and share Nepal’s marginalised histories. Curated by Diwas Raja Kc, it takes the form of a reflective collection of images, video and audio narratives which are contextualised by a curatorial text; situating them within the immediate temporalities of internet viewership. The materials presented here range from an archival map of the region, to an audio narrative describing the coming of the first tractor to the indigenous Tharu community, to beautiful landscapes of the forests and water bodies from the region.

Travellers cross the Narayani River at Pitauji Ghat, down the river from Narayanghat. Logs are piled across the river, which will be brought over to be hauled to India. (Photograph by Dave Hohl. 1967.)

Parts of Chitwan, a borderland once inhabited, cultivated and revered by the indigenous community, have been transformed into the Chitwan National Park since 1973. Now entry is restricted to tourists and urban dwellers who visit seeking to immerse themselves in natural beauty. The Skin of Chitwan digs below these projected narratives of national conservation to talk about the forced disruption of a native community and a way of being that has since been erased from the imagination of the country’s future.

In his curatorial text for the exhibition, Raja writes: “The dramatic consequence of climate change aside, the Anthropocene is also the story of how entire sensoriums of living, surviving, and thriving in entanglements with other beings are disposed for the reproduction of capital.”

New settlers in Chitwan being trained as “agricultural extension workers” about hybrid crops and the use of chemical fertilisers. (Photograph by Richard Pete Andrews. 1967.)

As an online presentation of sustained anthropological and photographic research, the website provokes the documentary modality, weaving together the various social realities of a wounded landscape—its soil, its forgotten deities and its resilient people—into a larger narrative about modernity and the Anthropocene. Questions about who and what is worthy of documentation emerge from these juxtapositions.

This sensorial immersion into the land moves the stories of Chitwan away from being dismissed as collateral damage in the global programme of modernisation. Raja writes: “Histories of dislocation often give past orientations a continuity—and not merely as memory—even as landscapes of inhabitance turn incoherent. Absences do not mean they don’t demand attention. They can be sensed as other modes of the present. They work on the world as oneiric prophecies.”

Settler town Narayanghat begins to sprawl on cleared forest lands. (Photograph by Richard Pete Andrews. 1968.)

In a public online presentation on the project at the time of its official launch, Raja described the thrust of the project to be a proposition to “…find archives where there are none.” Fragments of life from Chitwan—still and moving pictures of the quiet and unrelenting endurance of history—become a valuable resource for researchers, scientists and individuals confronting the challenges of climate change and perpetual planetary crises. As Raja writes in the curatorial text, “What was once reliably a metaphor for permanency, vitality, and equilibrium—the earth, the ground, the soil—is now a tectonic terrain of unrestrained calamity.”

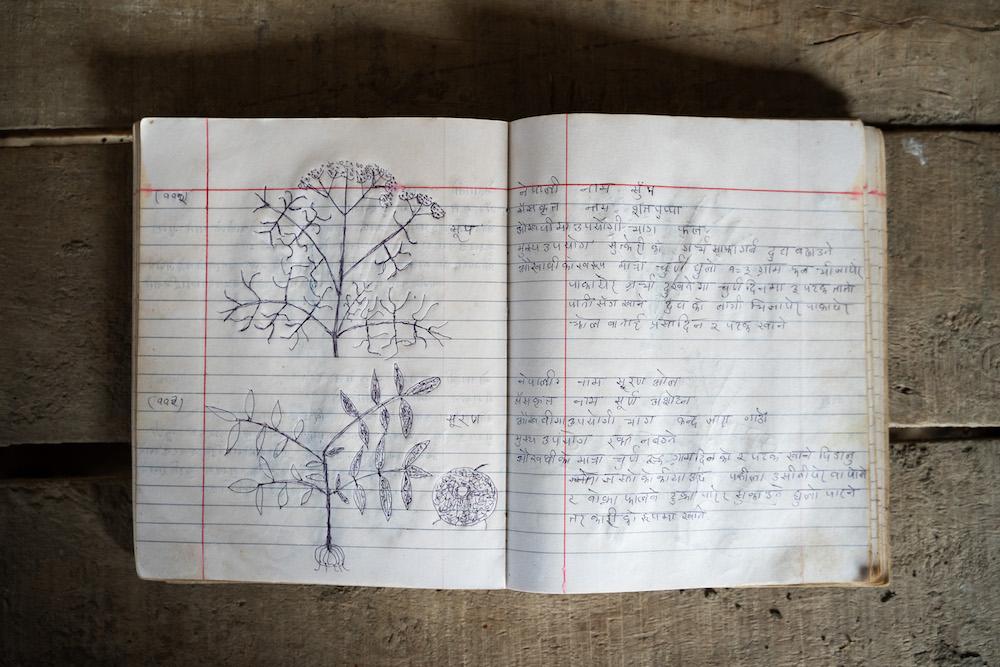

Pages from the diary of Ram Din Chaudhary, Jhuwani’s gurau (shaman).

To learn more about The Skin of Chitwan, please search for "Indigenous Pasts, Sustainable Futures: Images from The Skin of Chitwan."

All images from The Skin of Chitwan, Nepal Picture Library, 2019.