Accessing Excess in Mrinalini Mukherjee’s Archive: In Conversation with Archivists

The archive of prolific sculptor Mrinalini Mukherjee (1949–2015), digitised by Asia Art Archive, was recently launched on their website and exhibited at the Foundation for Contemporary Art (FICA) Reading Room. Beginning in the 1970s and comprising over 1,854 records, the archive documents Mukherjee’s engagement with unconventional materials, the varied sites and infrastructures that her work inhabited, and the personal and professional relationships she forged with individuals and institutions in the cultural field.

In this first of a four-part conversation with Noopur Desai and Pallavi Arora, who organised and digitised the collection, we focus on the extensive presence of visually dense photo-documentation in Mukherjee’s archive, and their granular experience of the materials as archivists.

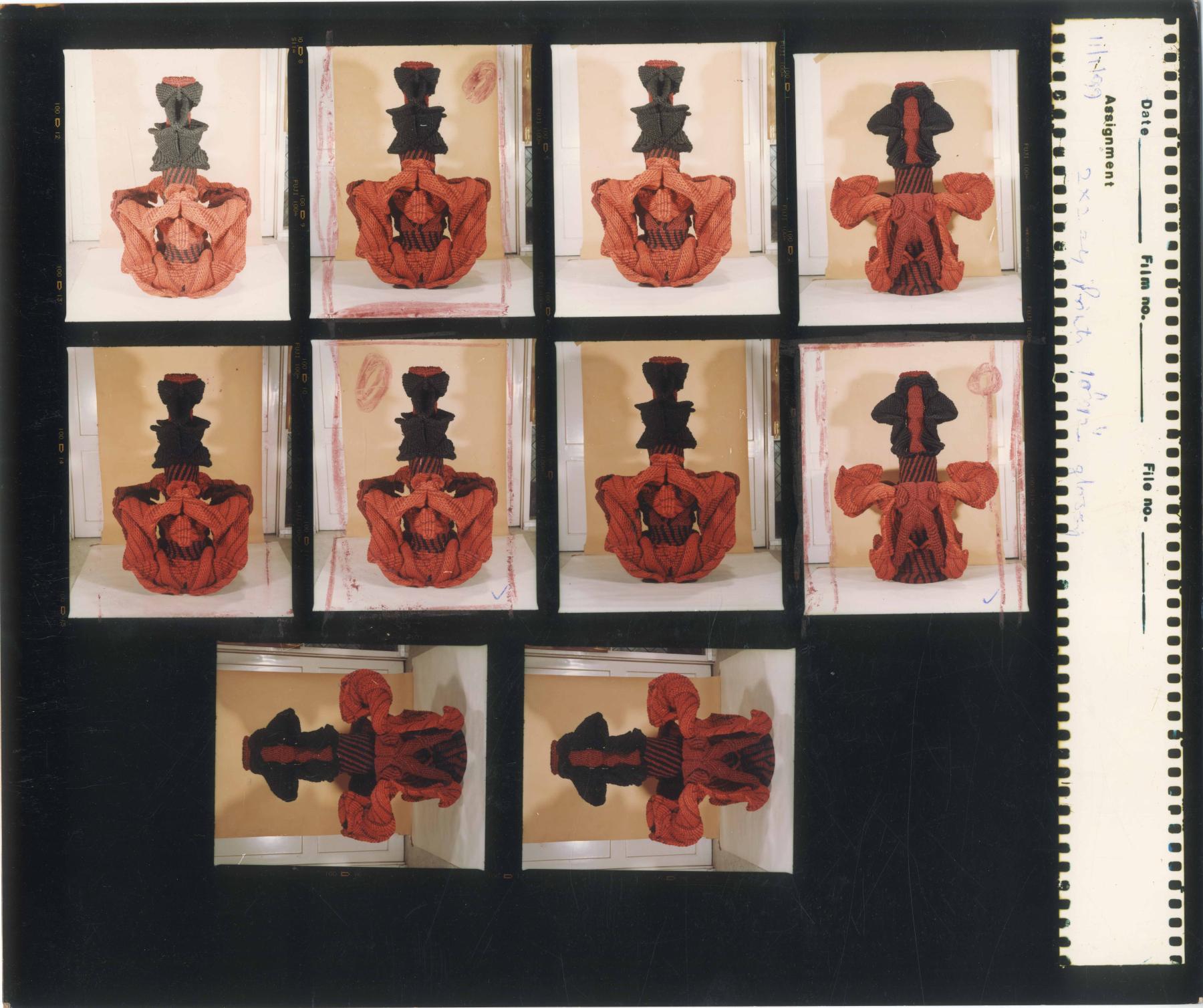

Contact Sheet with work Adi Pushp II (1998-99). Photo courtesy of Ranjit Singh

SB: A key set of materials within Mrinalini Mukherjee’s personal archives are the intensive photo-documentation of her work. Her sculptures are documented from multiple angles, sometimes with only the slightest shift of the lens, with multiple copies of contact sheets. As archivists, you were consumed by and immersed in this documentation, and have considered it to the point of excess.

ND: We had seen the materials in 2018, then housed at the FICA Reading Room, but we started in-depth scoping in early 2020. The first lockdown for the pandemic began soon after that, so we could not spend time with the archive in an immediate way, but after the city opened, we visited it once again and spent a month with the material. There were two cupboards full of contact sheets, negatives and 35mm slides. We used light-boxes to look at each and every image and material to see what was there—and what wasn’t. Only some of the material was annotated, but there appeared to be an internal logic to the organisation of the materials, which we tried to understand.

Our experience of the sheer surfeit of the archive did not happen at the moment of scoping but when we began to digitise, which is a much more granular engagement. We were overwhelmed by the material at that point, because it began to have a strained relationship with time. For instance, a set of sixteen slides or negatives would take about forty to fifty minutes to process, and it began to seem almost endless because there were thousands of slides to work on, and the idea of excess was starting to hit us. We brought the folders and boxes to our office, and as we would open one, there would be hundreds of negatives in it. We began to relate to some of what our colleagues have spoken about in the context of other extensive artist collections at AAA, such as Ha Bik Chuen or Jyoti Bhatt’s archives. Notably, there was an exhibition in Hong Kong in 2015 on Ha’s practice, titled Excessive Enthusiasm that we believe drew on the archivist’s experience of the materials as well.

It’s also interesting because when you spend that much time with each material, you are able to see the artist’s process in an intensive way, but at the same time start noticing their patterns, how they positioned themselves, and their ongoing interests in the archive, purposefully or otherwise.

PA: The entire process was characterised by this feeling of excess, and it was particular to our method. Usually, we organise the materials before we digitise them, but here we digitised everything before proceeding with the selection and organisation. There were also a lot of similar images, and it became difficult for us to gauge if these were separate or multiple copies—you had to strain your eyes to see the change in the angle of the photograph. Looking at one image repeatedly also creates a serial effect, wherein you begin to perceive it in movement, and it begins to gain an animated quality.

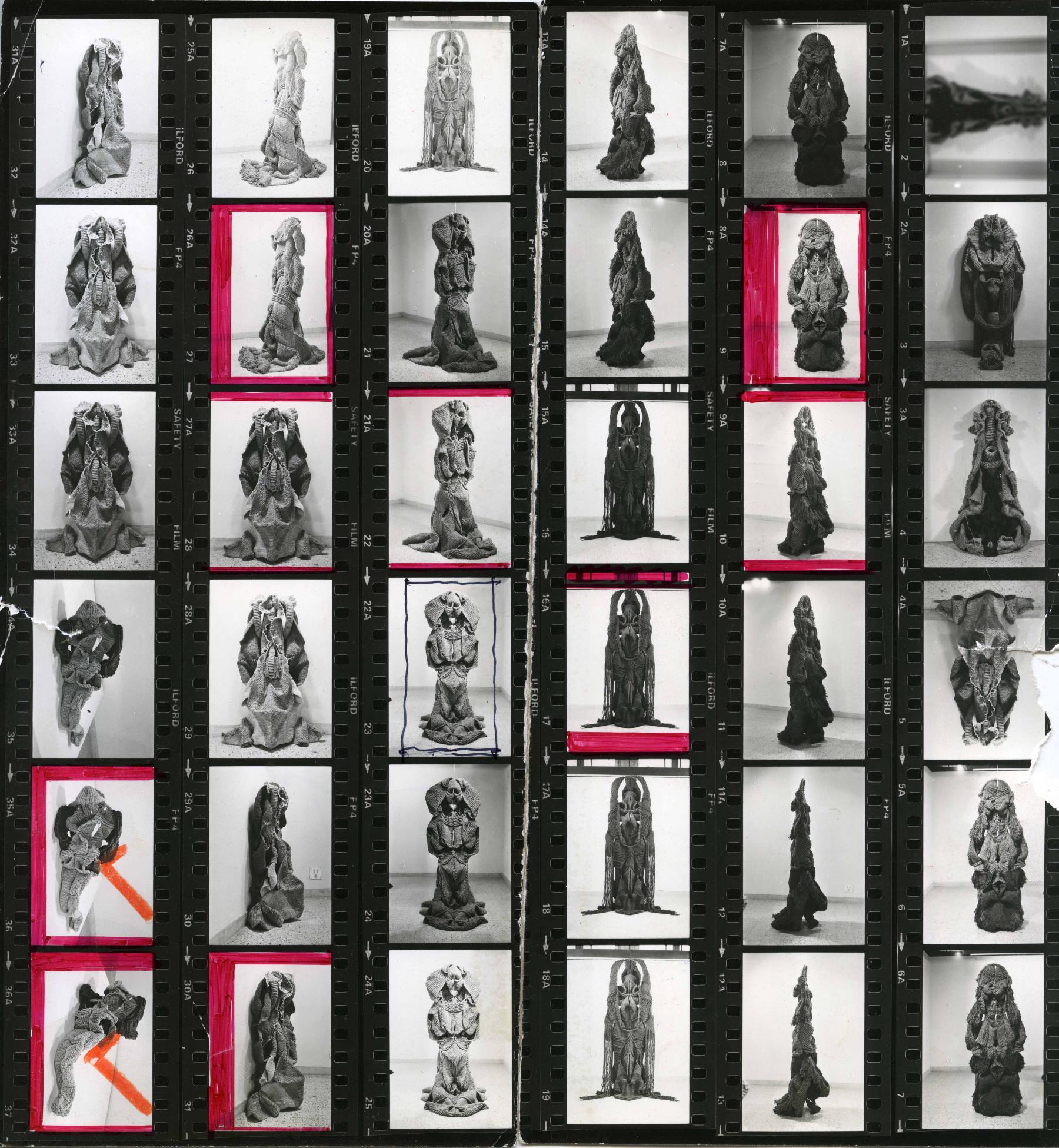

Contact sheet for multiple works including Kamal (1986), Purush (1980), Devi (1982), Rudra (1982), Pakshi (1985), Rituraja (1977) and Rati (1985). Photo courtesy of Ranjit Singh

SB: It appears that you are speaking of excess not in terms of volume, but repetition.

ND: Yes, and this can also be seen in the markings on the contact sheets. Mukherjee’s precise selections of the photo-documentation of her sculptures is evident, she would clearly highlight them (usually in red). To us, a lot of it looked the same, but there was clearly an image she had in mind that had to be realised and matched.

Another added layer to this process was when we began sorting the materials to upload online. We of course made selections keeping in mind the repetition, but we also negotiated with questions of how to could present the experience of excess on an online platform. I am not sure if the excess is palpable in the digitised archive.

SB: It definitely moved from excess to access in the process.

.jpg)

Contact Sheet for Ceramic Work (2001). Photo courtesy of Ranjit Singh

SB: In her monograph Mrinalini Mukherjee, Emilia Terracciano writes about how Mukherjee carefully selected photographers who were “architecturally savvy” but struggled to capture the essence of her work, and how Mukherjee was aware of the limits of photography. At the same time, Terraciano writes “…through photography Mukherjee plotted the ways in which sculpture could be experienced and animated.” Who were some of these photographers and what do you see in these photographs?

ND: The excessive documentation of her sculptures is about viewing the sculptures from different angles and perspectives, but what we also see is a spatial aspect to her sculptures. She was very particular about how her works were exhibited and displayed in relation to space.

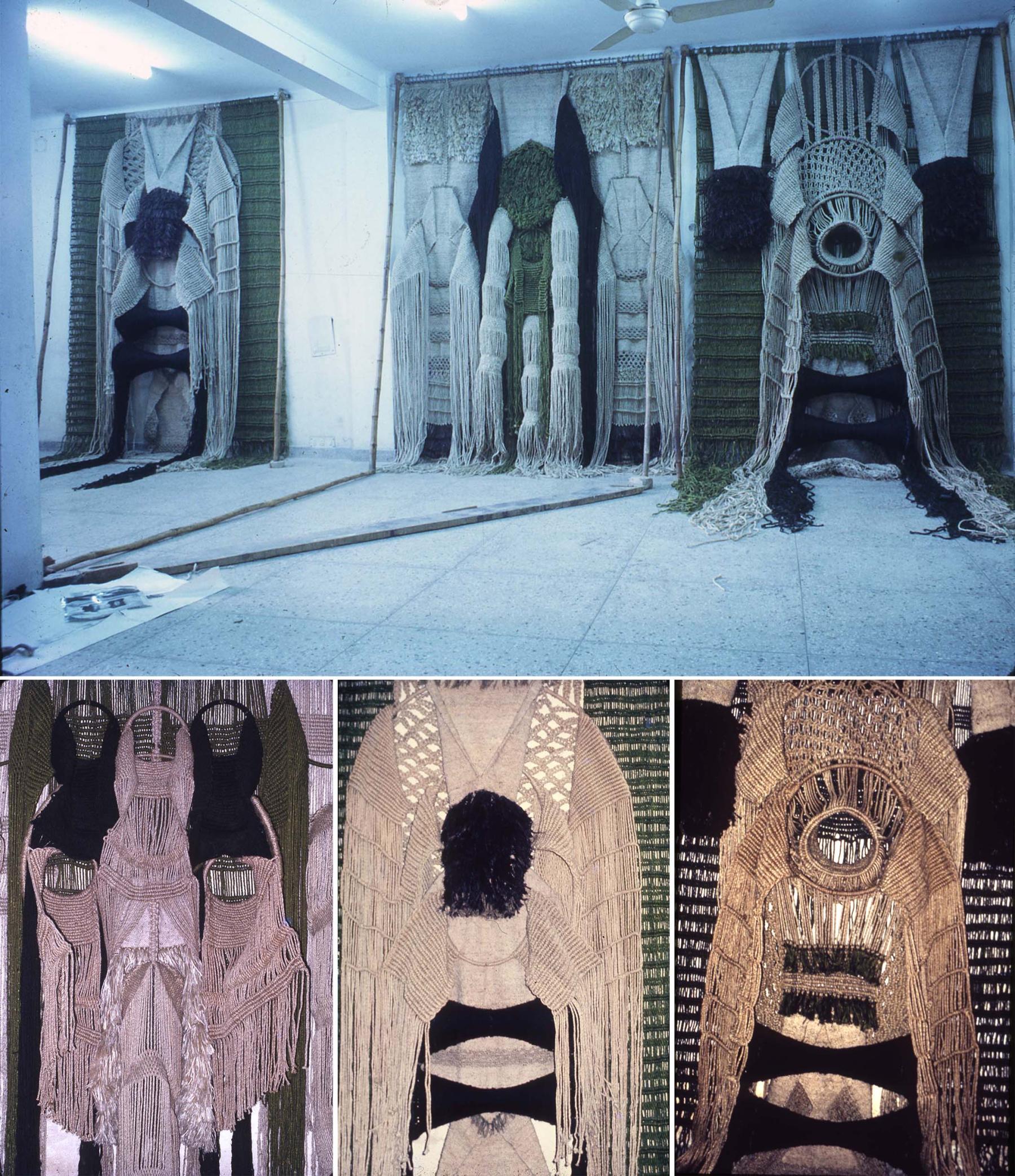

If you see Mukherjee’s earlier works from the 1970s, right after she graduated from the M.S. University of Baroda, she worked primarily on commissions from different architectural spaces; whether it is the mural she made for the Air India building in Washington DC, or the Mahatma Gandhi Institute Mural in Mauritius, her works responded to these spaces. When she moved to Nizamuddin, New Delhi in the 1970s, she was part of a hub of artists, designers, and architects who lived there, and with whom she worked closely, including her then husband and architect, Ranjit Singh.

Photographs of Mahatma Gandhi Institute mural, Mauritius (1976).

Singh documented a lot of her work, especially her early sculptures. Through these images you can access different spaces in the city—their barsati balcony with Humayun’s tomb in the background, different garages and shopfronts, outdoor spaces—all of these acted as sites and backgrounds for the photographing of her sculptures.

Professional photographers also documented her work, such as Avinash Pasricha, who during our conversations shared that he struggled a lot while documenting Mukherjee’s fibre sculptures in her garage studio. Because they did not have choreographed lighting present in exhibition spaces, he had to rely on natural light, which had a flattening effect. K.T. Ravindran was another architect who documented her work—there was a clear architectural lens in these photographs.

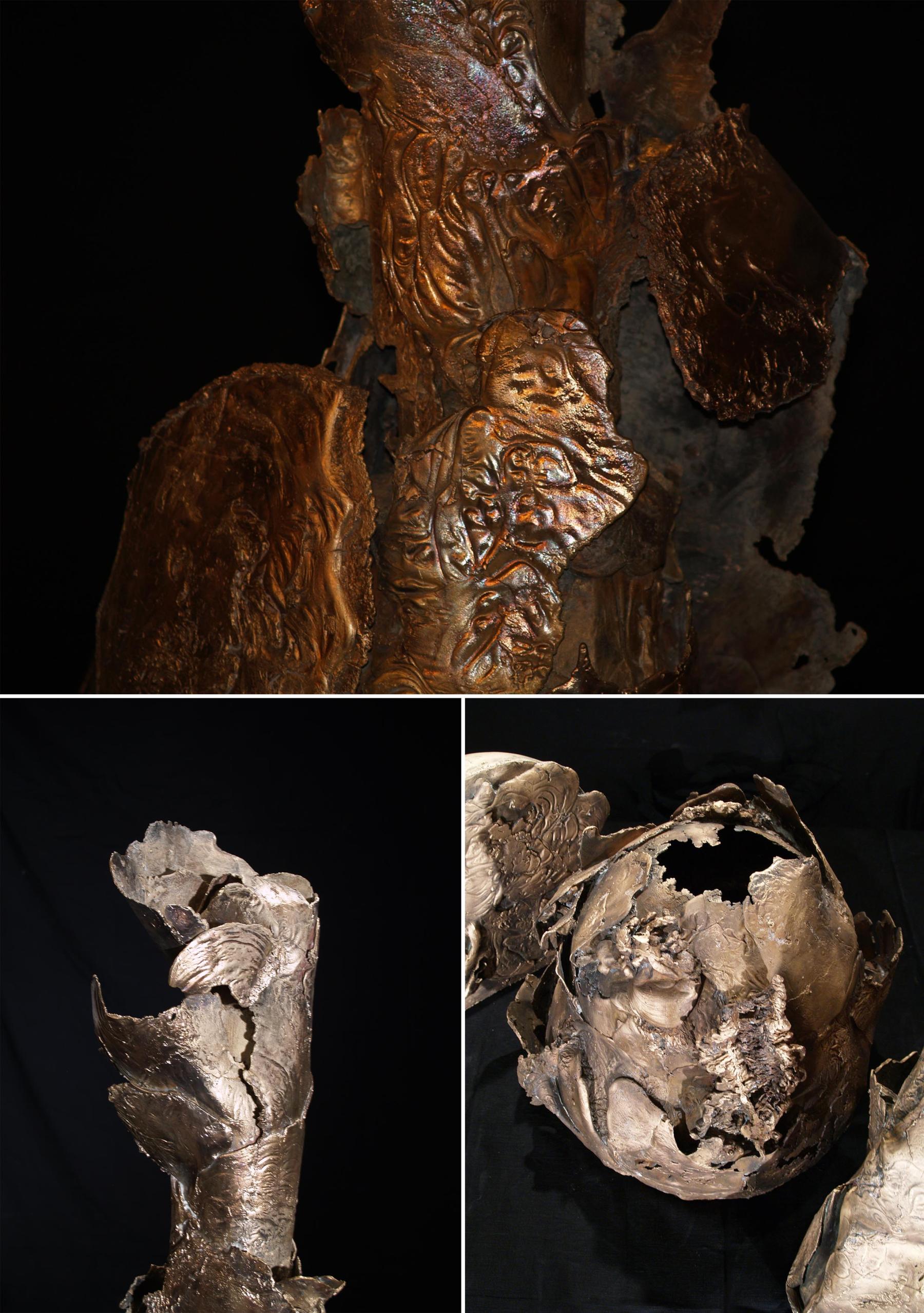

PA: Photographers such as Anna Tully also documented Mukherjee’s bronze works, and it’s fascinating because you can see her additive method when she works with ceramics and bronze. These are also evident in the installation experiments of her works, where you are able to see how she adds layers to her work rather than carving. You can also see the photographer’s own interest in Mukherjee’s work; for instance, Tully’s images are characterised by close-ups of the textures of the sculptures.

SB: I suppose we are all curious about how these images will circulate as Mukherjee’s archive is made accessible more widely, because her work is becoming increasingly precious, and one can only view it in limited institutional spaces. However, the photographs provide us with close-ups and angles we would not be privy to in person. The sculptures will have another kind of afterlife in these images.

ND: Yes, and it’s interesting because her fibre works especially are made of ephemeral materials, and so these photo-documents add another dimension of posterity to her practice.

Photographs of bronze works taken during Mukherjee’s solo exhibition. Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi. (2007) Photo courtesy of Anna Tully

All images are from the Mrinalini Mukherjee Archive, AAA Collections. Courtesy of the Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation.