Mapping Material Infrastructures: Mrinalini Mukherjee Archive

Vriksh Nata on terrace, New Delhi, 1991. Photo courtesy of Ranjit Singh

This is the second part of the ongoing series of conversations with Noopur Desai and Pallavi Arora at AAA, who organised and digitised the Mrinalini Mukherjee archive.

SB: A significant part of Mrinalini Mukherjee’s practice is about working in large scale, seen particularly in her hemp works. Additionally, her ceramic and bronze works tend to have an additive method. We find photo-documentation of her “artistic process” in the archives, but what do these images reveal?

ND: When we talk about the photo-documentation of Mukherjee’s artworks, we are interested in the different locations where the photographing took place. For instance, Nizamuddin East, where she lived, was one such site, then she had a garage studio in Khirki Village for some time, and she also worked at Garhi Studio as a part of a fellowship from the Government of India for many years. There’s also sites from her travels abroad—in 1996 she spent some time at the EKWC (the European Ceramic Centre, Netherlands) where had a large studio infrastructures provided by the Centre; she didn’t have that kind of space available to her in Delhi.

R: Wax moulds for sculpture in bronze at Garhi Studios, New Delhi, 2007.

L: Woman on Peacock (Work in Progress), New Delhi, 1991. Photo: Ranjit Singh.

Apart from the varied sites where her work was produced, you also get glimpses of those who helped her construct her large-scale works—friends and assistants, and often her then-husband Ranjit Singh. It’s clear that it wasn't possible for her to work at such a scale on her own.

In one of her lecture notes, Mukherjee discusses her process, “I have to start from somewhere, but then I let it grow”. Through these images, we are able to see how she begins with an armature, and how hemp ropes allow her work to “grow in all directions”. She would undo and redo the knots, which would eventually become her monumental sculptures. The photographs show us some unfinished stages of her works, where the ropes are yet to be knotted. The images also reflect an additive method that Mukherjee used in her bronze and ceramic sculptures. Artist and theorist Kristine Michael, who worked closely with her, also speaks about how Mukherjee would create a mould and then add different parts to her ceramic works, before they fired the sculpture.

L: Yogini (Work in Progress), New Delhi, 1986. Photo courtesy of Ranjit Singh.

R: Work in progress at European Ceramic Work Centre, Hertogenbosch, Netherlands, 2000.

SB: I was struck by one of our earlier conversations, where we discussed how even these in-process images appear staged and choreographed. On the other hand, you don’t see any sketches, blueprints, maps, models or any kind of notes about how she made her work; thus, the photographs become our clues.

PA: We also see how Mukherjee stages herself with her in-process works, posing for the photographs as if she is in the process of knotting it, but the images don’t really provide a clear sense of the process. You do see the stages, in some cases, but mostly you get glimpses of other things—armatures, sites, infrastructures. The archive doesn’t tell us, or we cannot see, where she sources her material from, what her dyeing process was…

ND: …and even the little we know about the above is because of conversations with her peers in the process of putting this archive together.

In terms of the sketches and notebooks, as we considered the archive internally, as a team, it became evident to us that we won’t be able to obtain a sense of the process of measurement. We considered forms like crochet and embroidery, and how there’s some sense of rows, columns and marking before the work is made. We don’t see any of this with Mukherjee. This is what made us turn to her few lecture notes, to make sense of her method, and this investigation is also what underlines our exhibition. We realised that what was happening was more embodied and visual, and not marked in documents the way we expected.

Garage Studio, New Delhi, 1985. Photo courtesy of Ranjit Singh

SB: The photographs in-process are also quite neat, if I may say so, and so we what we access from the archive is quite carefully framed–perhaps that’s what photography as a medium also lends itself to, which is selectively seeing.

I want to go back to something you touched upon earlier, about how the scale and labour intensive materiality of Mukherjee’s work was not possible without help and joint effort. Who else do we see in the documentation of her artistic process?

ND: When you see some of her earliest works from her student days at the Faculty of Fine Arts at M.S. U. Baroda, she’s working together with her friends, with the fibre on the ground. You also see her trying to hang some of the sculptures outside the mural department with them—this element of working with others appears to be evident from earlier days.

When Mukherjee moved to New Delhi and met Ranjit Singh, he began to appear quite a bit in the photographs because she worked closely with him; from traveling together to source the fibre from markets to the actual making of the work. He would also often be behind the camera, documenting under her direction. An important and consistent assistant for her was Budhiya, who was also her domestic help; she is a strong presence in the archival photographs.

Mukherjee’s assistant Budhiya working on fibre sculpture, New Delhi. Photo courtesy of Ranjit Singh

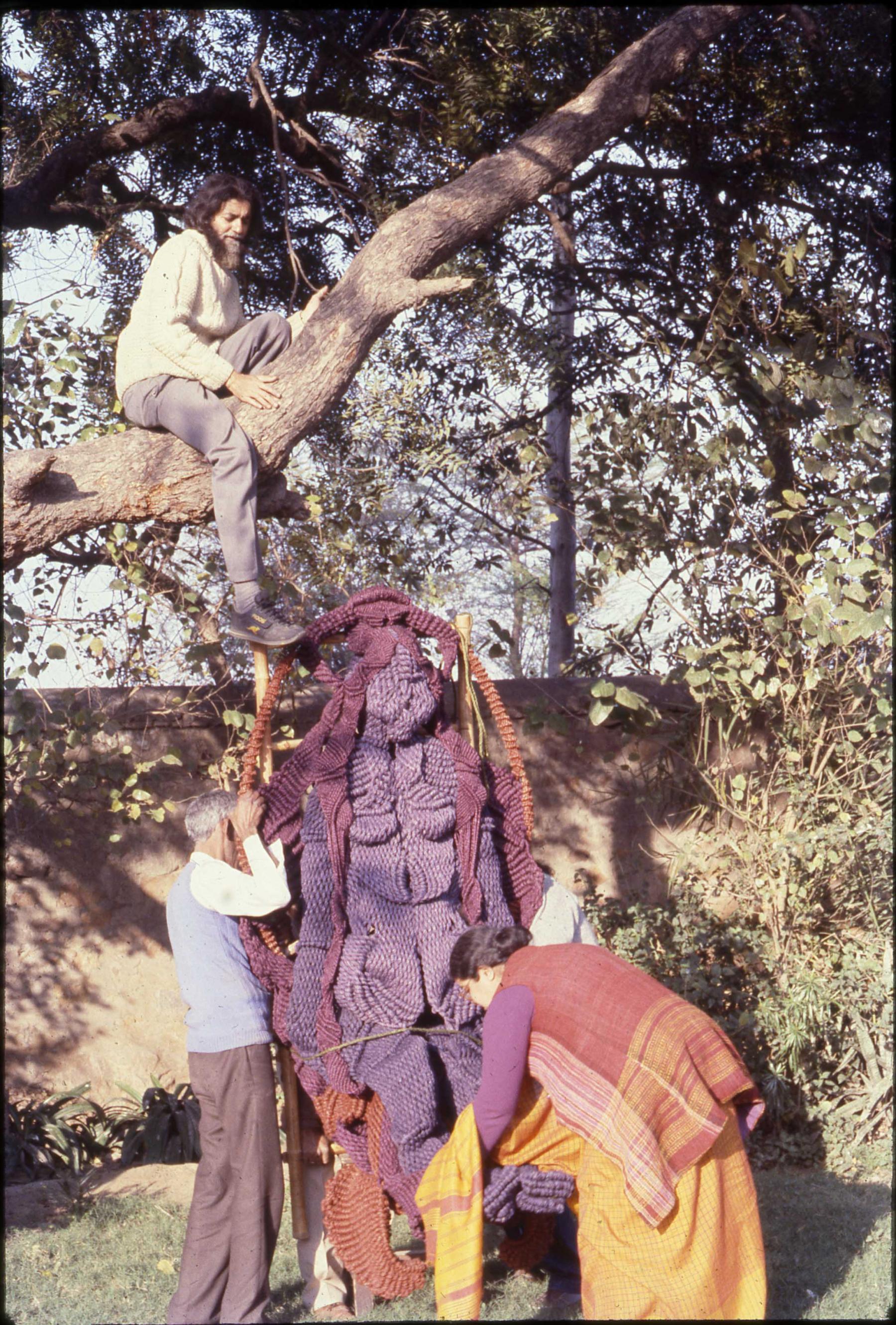

We all love this one photograph where she’s experimenting with installing her work, Woman on a Swing (1989), outdoors. We can see Manjit Bawa, a close friend of hers, sitting on a tree branch holding the top part of her work and she’s at the bottom fixing it. In another image from Sanskriti Kendra in New Delhi, the artists Sheila Makhijani and Kristine Michael are seen helping Mukherjee carry her work after firing. Her friends keep appearing in the archive.

Woman on a Swing installation experiment, 1989. Photo courtesy of Ranjit Singh

To read the first part of the conversation, click here. To read more about archival afterlives, click here, here and here.

All images are from the Mrinalini Mukherjee Archive, AAA Collections. Courtesy of the Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation.