Building an Archive: The Confluence Collective on Retelling Histories

A six-member collective of photographers and researchers—consisting of Mridu Rai, Dipti Tamang, Ashwin Sharma, Shivam Darnal, Kunga Tashi Lepcha and Praveen Chettri—came together to form The Confluence Collective in 2020. Over an email exchange, the collective responded to their very organic formation, which was driven by the fact that all of them had been collaborating closely on personal and professional projects since 2016. Interested in researching and working with the larger region of the Sikkim-Darjeeling Hills, their practice as a collective became instrumental in establishing a platform to illustrate an inclusive history of the area through the documentation of visual archives and oral histories.

Annual village picnic, Mungpo, 1950. Image courtesy of Dipti Tamang, The Confluence Collective Photo Archive.

The Confluence Collective decided to focus on the Sikkim and Darjeeling Hills as all of the members identify with the need to bring forth the origins of their local cultures. Engaging strongly with visual mediums, the collective works as a channel that connects the past with the future. They communicate their research through photography as an art form, which for them, “…deliberates, speculates and creates collective engagement.”

Hand coloured Tibetan Muslim family portrait of Lt. Faizullah Chishti’s family, Kalimpong, 1963. Image Courtesy of Sufian Chishti, The Confluence Collective Photo Archive.

There is a certain subjectivity that accompanies the creation of archives. The voice of the person documenting a photograph or story as an object creates an inherent layer of situating information, which eventually becomes part of the larger representation of a group. The collective deliberates on the need to create an archive at a time when the subjectivity of existing archives is being questioned. Commenting on the forms of othering present in most perspectives of the region, the collective highlighted the “outside” gaze on their region, understood through the abundance of “snowy mountain peaks, lush tea gardens, women in ethnic outfits” and other colonial viewpoints. The images and stories compiled by The Confluence Collective recontextualises photography in the region, allowing visual narratives to bring forth often-ignored voices and moments in time through family picnics, personal struggles and aspirations in the Sikkim and Darjeeling Hills.

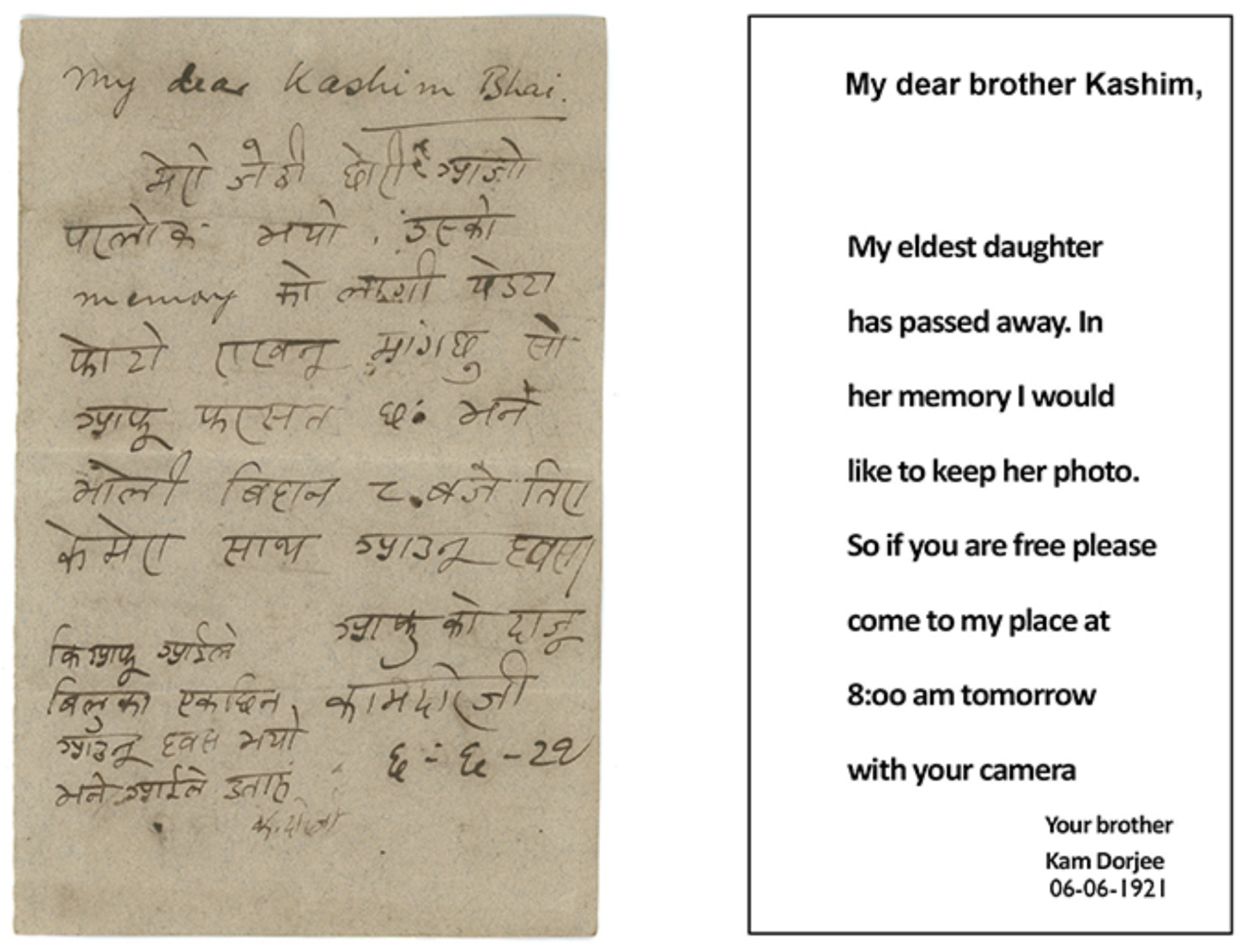

A Letter to the Photographer Kashim Ali, 1921. Image courtesy of The Confluence Collective Photo Archive.

Through their practice, The Confluence Collective strives to combat the one-dimensionality of narratives in archives by presenting new ways of looking. They cite the example of Sikkim, a region that is primarily exoticised for its natural beauty. This has led to Sikkim becoming a major tourist attraction, resulting in an increase in the number of construction sites to accommodate the tourism industry. While it may be analogous to term such expansion as “growth and progress”, it is instead an instance of hegemonic regression. Through the process of reopening personal and family collections in the region, the collective aims to build an archive that becomes a source of knowledge production and offers a conscious retelling of histories as they seek to undo colonial perspectives of the region. In this manner, they hope to create an archive that celebrates and nurtures the local and individual cultures of the Hills.

Family portrait. S. K. Singh Studio, Darjeeling 1952. Image courtesy of Palsang Lama, The Confluence Collective Photo Archive.

The archive began with contributions from the members of the collective, and their families and friends. As it gained traction, the collective was approached by people from across the region who wanted to add their own stories. These contributions have helped the collective’s efforts of documenting local narratives and histories to emerge as an extremely significant intervention in the region.

Ishita Rai Dewan sharing details about her family album photographs. Image courtesy of The Confluence Collective Photo Archive.

Apart from personal or family histories, the collective also recognises the need for including institutional images in their archive. They have gathered images from local institutions such as Dr. Graham’s Homes in Kalimpong and a large collection of images by Tse Ten Tashi, one of the first practising photographers from Sikkim. In this manner, the collective aims to document and collect stories of folklore, tradition and local knowledge through their visual and oral archive.

Sobit volunteered to help the collective digitise the Dr. Graham's Homes school archive. Image courtesy of The Confluence Collective Photo Archive.

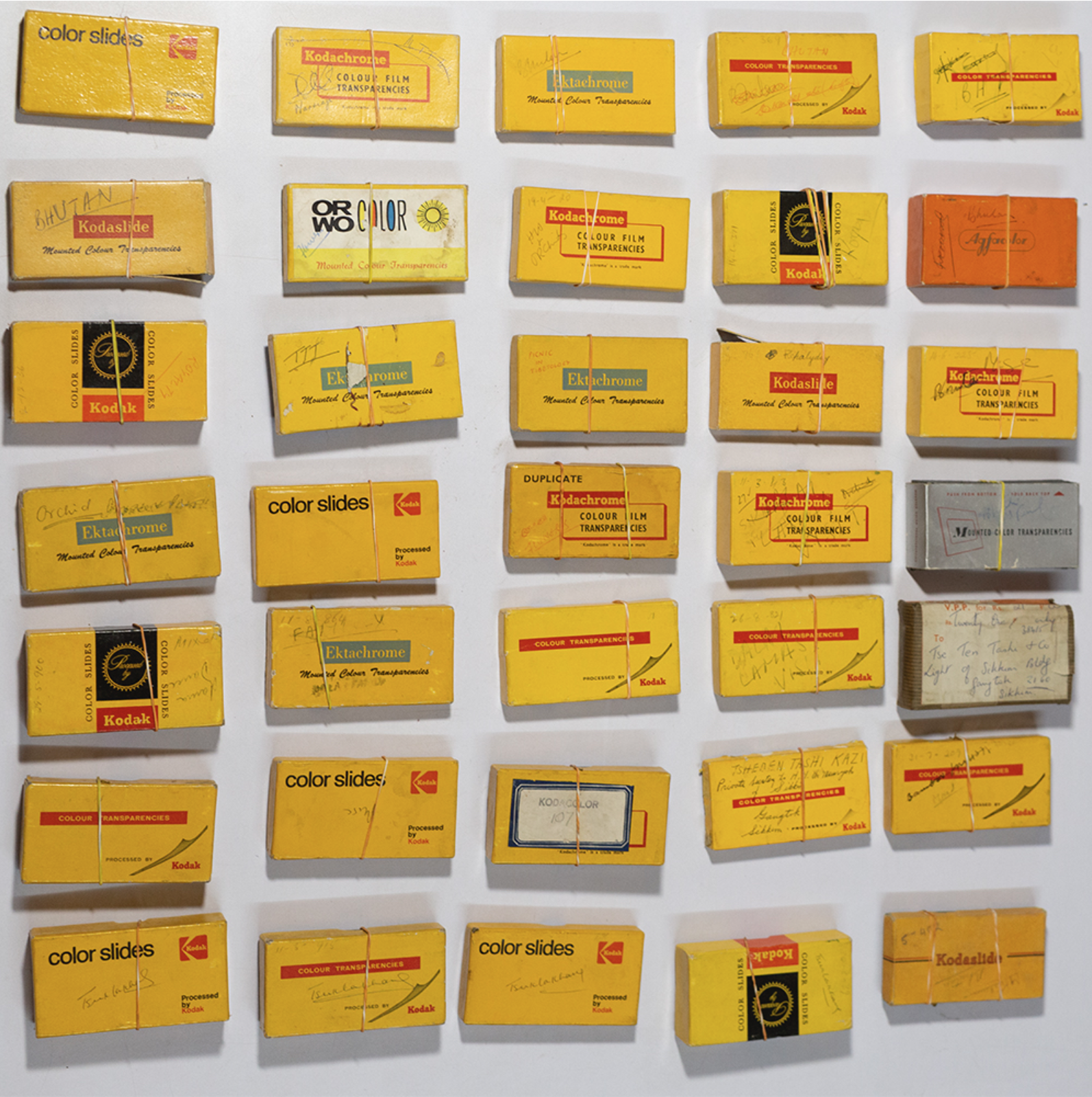

Slide boxes belonging to Tse Ten Tashi, the Court Photographer to the Chogyal of Sikkim as well as the Druk Gyalpo, the King of Bhutan. Image courtesy of The Confluence Collective Photo Archive.

Another attempt by the collective to think through the nature of representation in the archive is by reflecting on conflict in the region. Political unrest in the Darjeeling Hills is supressed by the notion that a visually disturbing presence is required for conflict to exist. Dipti Tamang writes:

“Our perceptions of conflict is such that unless it is obvious in its most bare form—as raging sites of battlefields, gun-wielding warfare and violent confrontation—we barely acknowledge the presence of conflicts where such sites of direct warfare is not involved in its most obvious forms. The conflict in Darjeeling Hills is not recognised precisely due to this perception of conflict that predominate our imaginations. Further due to the cyclical nature of the conflict, long periods of ‘peace’ in between these cycles obscures the presence of conflict in the region, simply understood as a ‘law and order’ problem.”

Debt of mother tongue has to be paid, Kalimpong 1970. Image Courtesy of Sufian Chishti, The Confluence Collective Photo Archive.

In referencing the visual socio-cultural aspects of an archive, The Confluence Collective draws closely from and is inspired by the works of the Nepal Picture Library and other art and photography collectives in South Asia. They carry forward Nepal Picture Library’s aim of creating a visually dense history of Nepal and populating the gaps of historic socio-cultural knowledge in the region they work in.

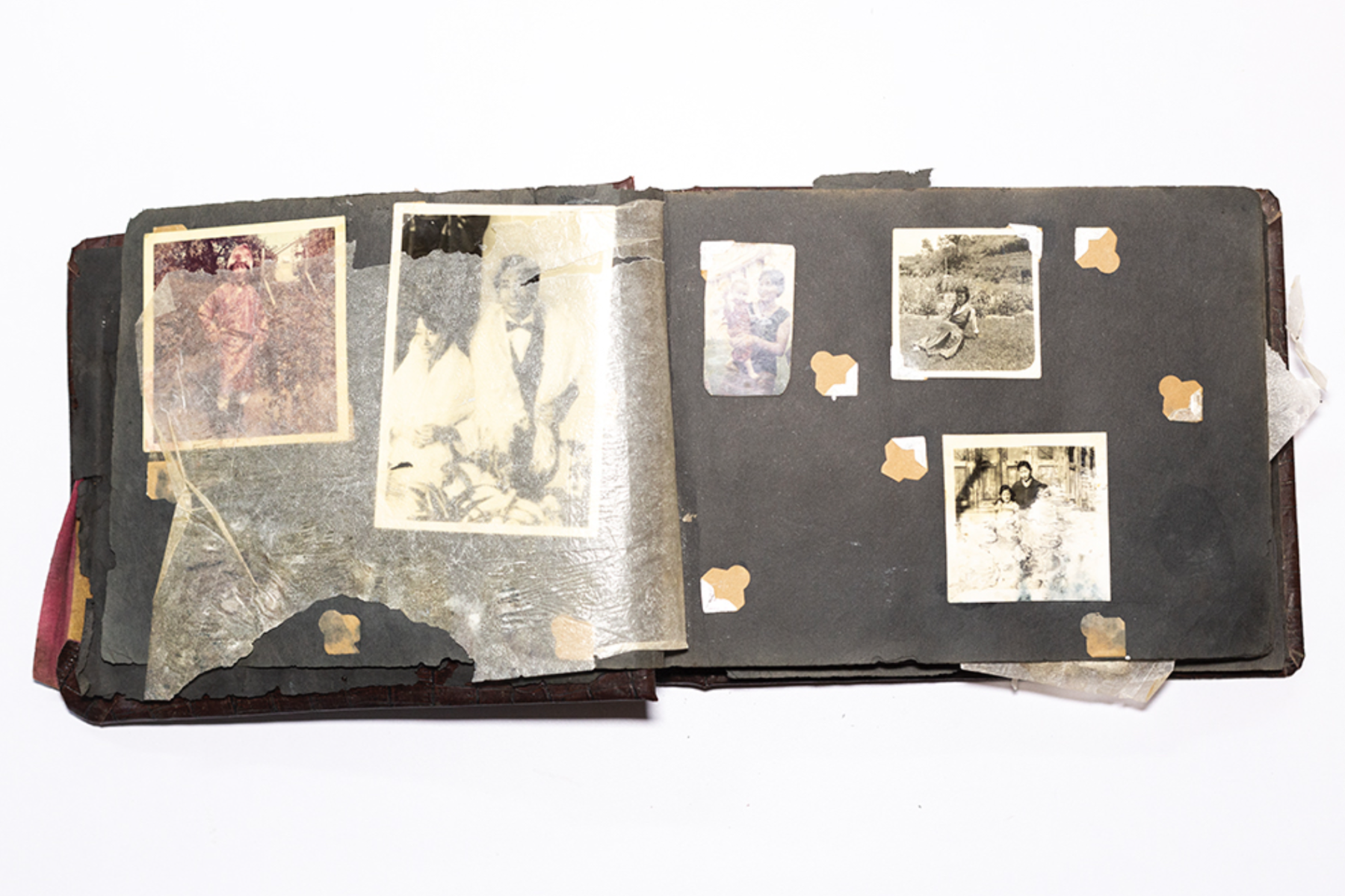

Found album belonging to Kesang Dichen. Image courtesy of The Confluence Collective Photo Archive.

Each member of the collective is highly aware of their role in determining future readings of the archive. By addressing the fact that they were not taught their local histories in school, but instead that of mainland India; they are driven by the need to create local knowledge through the archive. This involves the need to understand themselves through the process in order to be able to understand and mediate their narratives in storytelling.

All quotes and references cited here are from email exchanges between The Confluence Collective and Veeranganakumari Solanki, which took place in September 2021.