Memories of a Movement: On Ajay Bhardwaj’s When the Tide Goes Out

Ajay Bhardwaj’s documentary When the Tide Goes Out (2021), recently screened at the Kolkata People’s Film Festival, revisits the Canadian Farmworkers’ Union (CFU) and its active members through the 1980s. The CFU was founded in 1980, after a meeting of South Asian community activists in 1978 at a school in Surrey, British Columbia. It was led by immigrant communities from the Indian subcontinent—primarily Punjabi workers from India. The CFU went on to become a nucleus of cultural memory for the radical contributions made by these communities to the larger social imagination of Canada. Solidarity between the CFU and other Left political and cultural organisations in Vancouver sought to build a narrative of visibility for Punjabi-Canadians. They supported the fight for workers’ rights, as well as actively campaigned against the racial discrimination that plagued the community’s chances of finding justice in their adopted country.

CFU traces its existence to influential writers and journalists such as Sadhu Singh Dhami who moved to Canada as a teenager in the 1930s. Dhami connected the waves of political activism inspired by India’s freedom movement (with the Ghadar party as a special source of influence) to labour rights and trade union activism in Canada. He eventually retired from the International Labour Organization before his death in 1997. Dhami’s semi-autobiographical novel Maluka (1978) depicts the early years of Punjabi immigrant presence in Canada, describing the protagonist’s association with workers from Punjab who exhort him to secure an education: “Don’t end up like us, with sawdust on our turbans and sawdust in our hands.”

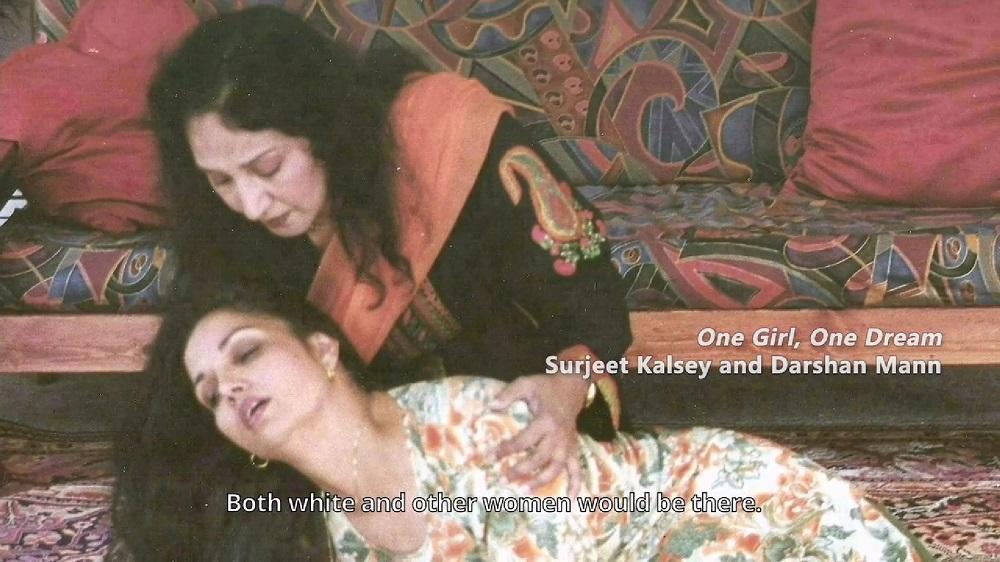

Bhardwaj’s documentary revisits the Punjabi-Canadians who were active members of the CFU through the 1980s—picketing factories, leading protests and producing theatrical works as well as cheaply made home movies and magazines. The monthly literary magazine Watno Dur (Far from the Country) formed an important archive of precedents and political opinion in this capacity for the cultural arm of the movement, that came to be known as the Vancouver Sath.

What could have been a film that relied on the transparency of the cultural document in representing the image of a holistic past becomes, in Bhardwaj’s conscious and complex handling, a platform for self-critique. How does one remember a movement that is full of cracks and silences that do not appear in its documentation? Cracks, which are not apparent in the images, or silences that are not audible to researchers become problematic when relying on the promise of those documents to tell a complete story instead of a dangerously partial one. Jean-Luc Godard would famously articulate the paradoxical, confabulatory potential of image-making in contexts of seeking justice when he spoke about the difference between a “just image” and what was “just an image.”

These questions take centre-stage as the film progresses, displacing the comfortable conspectus of a solidarity movement from the past. Bhardwaj focuses especially on the absent narratives of women workers in the union and outside. The structural reality of gender inequality manifested in patriarchal restrictions and, often, domestic violence as well as harassment at the workplace—which ranged from dismissals to sexual misconduct by the predominantly white managerial staff. A lot of the protests and picketing featured women in the foreground, as depicted in some of the images. They fought for the right to be recognised as working Punjabi women, asserting their mark over an alien landscape.

The documentary asks questions around personal memories of the past. It examines how these intersect with or bolster the collective memories of communities in solidarity with each other, as they work to achieve larger goals in public life. What were the silent sacrifices made to document such solidarity—and does that document then assume the status of a subversive and uncomfortable fiction? The work of photographers and artists, such as Claire Kujundzic and Anand Patwardhan—who made one of his early films on the CFU, titled A Time to Rise (1981)—becomes important. How does one consider questions around the CFU’s acts of protest and solidarity with workers’ rights, while recognising the personal unhappiness faced by the many women who fought battles on multiple fronts in their struggle to be recognised as immigrant citizens? Several decades after the events depicted in the film, union workers suggest that these battles fought by women could often simply mean a range of sites where their presence and struggles were ultimately forgotten. Even as Bhardwaj’s film attempts to re-create the past of a solidarity movement, it deftly interrogates the gaps that inevitably shape an archive of resistance, asking the audience to confront their own impulses to separate the personal from the political.

To read more about films screened at the Kolkata People’s Film Festival, click here.

All images from When the Tide Goes Out (2021) by Ajay Bhardwaj. All images courtesy of the artist and Kolkata People’s Film Festival 2023.