A Double Elegy: Farha Khatun’s Ripples Under the Skin

While watching Ripples Under the Skin (2021), Farha Khatun’s poignant portrait of the dying profession of bhisti (urban water-carriers), the real surprise, one feels, is that there are still a few of them around. Defiantly anachronistic, they continue to pour “sweet water” from plastic jars into their mashaq (goat-skin bags) before conveying them to nearby homes and local establishments that do not have access to the municipality’s water-supply. The documentary, which was screened during the Kolkata People’s Film Festival 2023, tells the story of Sheikh Nazim, a migrant worker in his sixties, who continues to ply his trade in central Kolkata against all odds.

Nazim with his mashaq en route to a delivery.

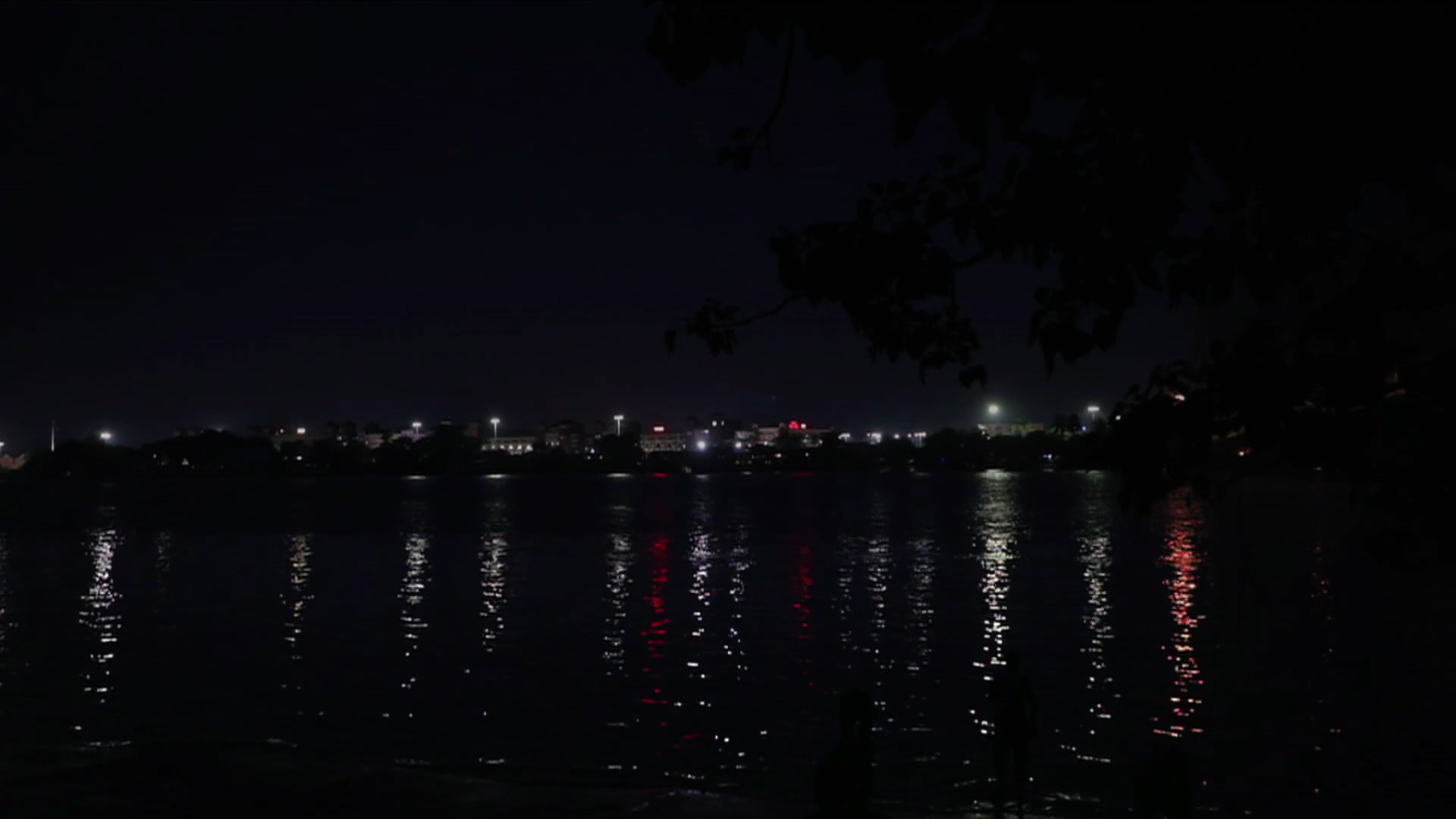

A bhisti’s day starts well before the first crack of dawn. Kaak-bhor i.e., the hour at which crows can only be heard, as it is known in Bangla, is when the film begins its journey alongside Nazim chacha. He sets off on his lopsided walk down dark bylanes, observed by silhouetted birds from tree-tops and lampposts. As the camera positions itself atop a staircase inside a house, waiting for him to catch up, we hear the narrator (Monalisa Mukherji) explain that bhisti comes from the Persian word behest or “heaven” and behesti or “one who belongs to paradise.” The bhisti does not distinguish between religion, caste or creed but knows only those who are thirsty and parched.

Tank Square and water carriers, Calcutta (1851) by Frederick Fiebig. Image courtesy of British Library.

We learn that Nazim had come to the city several years back in search of a livelihood, after having tried his luck in the fields in his native Bihar and in Nepal. In Kolkata, he started out as a scrap-collector in Metiabruz, a locality situated close to the docks in the south-western part of the city, before moving to the central districts and learning the bhisti’s work from a cousin. He subsequently procured his license and equipment for Rs. 5000. At present he earns ten rupees per mashaq for ground and first floor deliveries, and between twenty and thirty rupees for the upper storeys, with a daily tally of about thirty to forty refills. The film also makes a fascinating pitstop at Sk. Shafiq’s workshop, which is the only place in Kolkata that repairs mashaq, before setting off with Nazim on a journey to his home in Barsoi village in Katihar district. The film then introduces viewers to other members of Nazim’s family—perhaps also by way of explaining why farming alone is not enough to sustain them.

Nazim tending to his crop in Barsoi, Katihar. The motif of ripples—in ponds, the Hooghly river, and in puddles—recurs throughout the film.

The self-awareness with which the film incorporates the historical and archival is remarkable. Mukherji’s voiceover relays the story of Abbas, the fabled first bhisti, who is said to have brought water from Furat (Euphrates) to Imam Husayn’s army on their way to Damascus during the Battle of Karbala in 860 CE. Predictably, this incident is found in more than one version. Later, we hear the story of Nizam, a bhisti who saved the life of Emperor Humayun during his battle with Sher Shah Suri. As a reward, Nizam sat on the throne of Agra for a day. The story was charmingly cited in the narration as having been found “in the museum archives.” The British colonial fascination with the bhisti is alluded to as well, in the form of visual collages in the title and end credits. Towards the end of the film, we come full circle to see two images of the mashaq frozen in museum displays at the City Centre shopping mall in Salt Lake, Kolkata, and inside a renovated luxury heritage establishment. The director refrains from commenting on the irony, thereby ensuring that the film’s focus remains firmly on Nazim’s story.

A cast-iron sculpture of mashaqs at the City Centre mall, Salt Lake, Kolkata.

This sensitivity is noticeable in other aspects of the film too. Given how easy it is to lapse into nostalgic, colonialist narratives about the city, Khatun successfully navigates through a maze of hackneyed representative strategies to share her personal involvement with Nazim’s life and work. This is evident in the pacing of the film. A few evocative sequences in particular deserve special mention in this regard: the opening shots of Kolkata coming to life, and the sequences in the train and in Barsoi. In the latter especially, the cinematography and editing create a richly sensorious experience for the viewer, as if to lure us into believing that we are co-travellers.

The film also addresses its own volatile political context with great subtlety. Khatun met Nazim in 2019, around the time of the nation-wide anti-CAA-NRC protests. The profound irony of the claim made early in the film about the bhisti not discriminating between religious or caste identities is presented with the protest posters and graffiti visible in some shots of the cityscape. The montage frees the protagonist of bearing the burden of standing in as a political symbol, with meaning-making emerging instead through an unarticulated transaction between the filmmaker and viewer.

Nazim at a street-corner with a campaign poster against NRC and CAA behind him.

Ripples Under the Skin was produced by the Films Division of India in 2021. Under the present context of the merger of the Films Division of India and the National Film Archives, it is difficult not to view the film as a double elegy: to a profession and to a cherished institution. During during the Q&A, when asked by the writer what she feels the future might hold for such projects, Khatun, a two-time recipient of the President’s National Film Award, responded that the Films Division had felt like a “safe space” for many filmmakers like her, and she hopes that these spaces of productive engagement will remain accessible in the future too.

To read more on films screened at the Kolkata People’s Film Festival 2023, click here and here.

All images from Ripples Under the Skin (2021) by Farha Khatun, unless mentioned otherwise. Images courtesy of the artist and Kolkata People’s Film Festival 2023.