Of Familial Matters: Don’t Worry About India by Nama Filmcollective

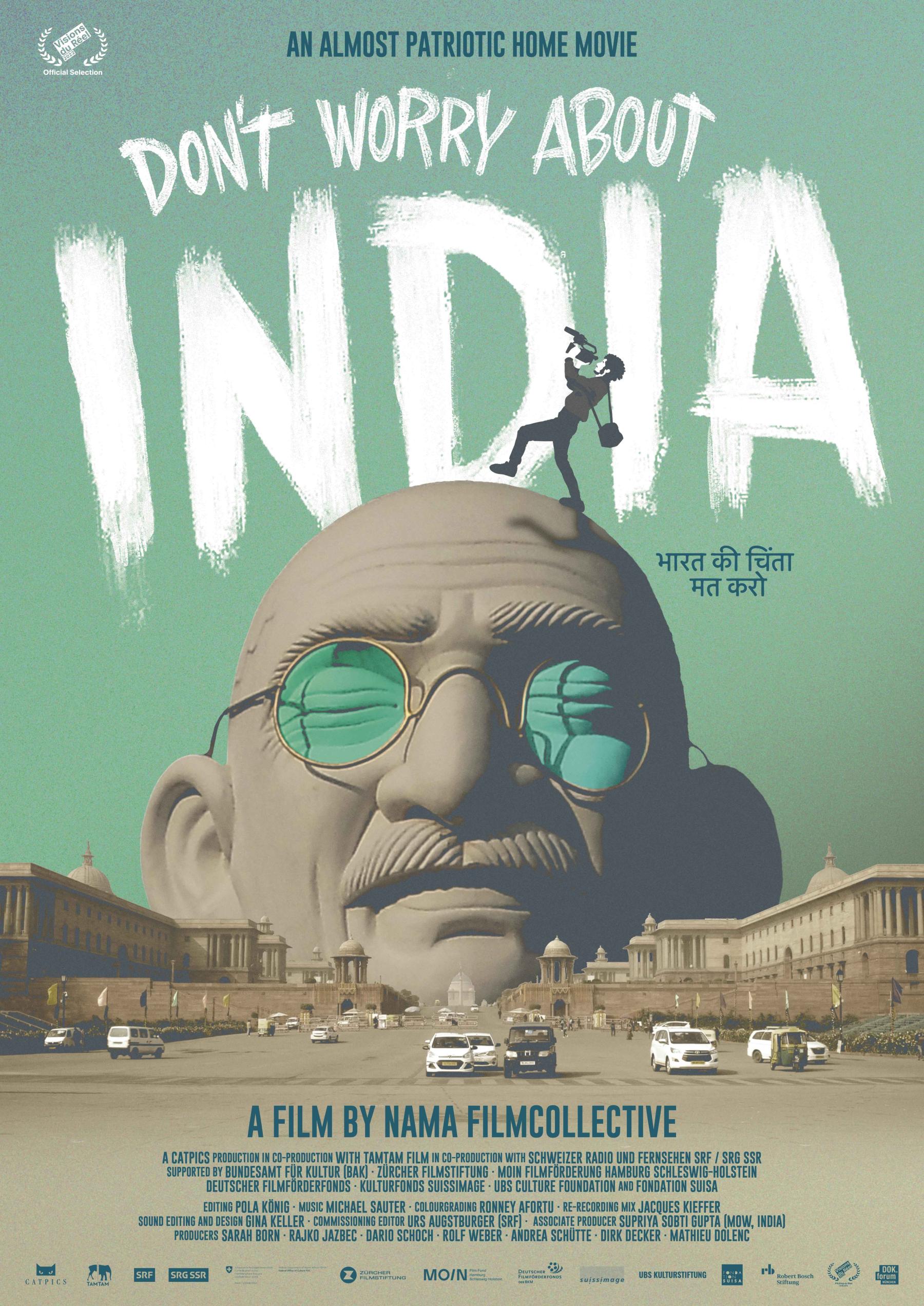

Recently screened at the Kolkata People’s Film Festival 2023, Don't Worry About India (2022) by Nama Filmcollective charts the 2019 Lok Sabha elections in India through the personal acquaintances and familial associations of its protagonist. The film deploys an even-tempered language operating along the intersecting axes of the genres of a home movie and a road movie. Steeped in dry humour and a darker shade of irony, the film uncovers its protagonist's intergenerational political ignorance as he travels across the country amid the resurgent wave of Narendra Modi’s return to power.

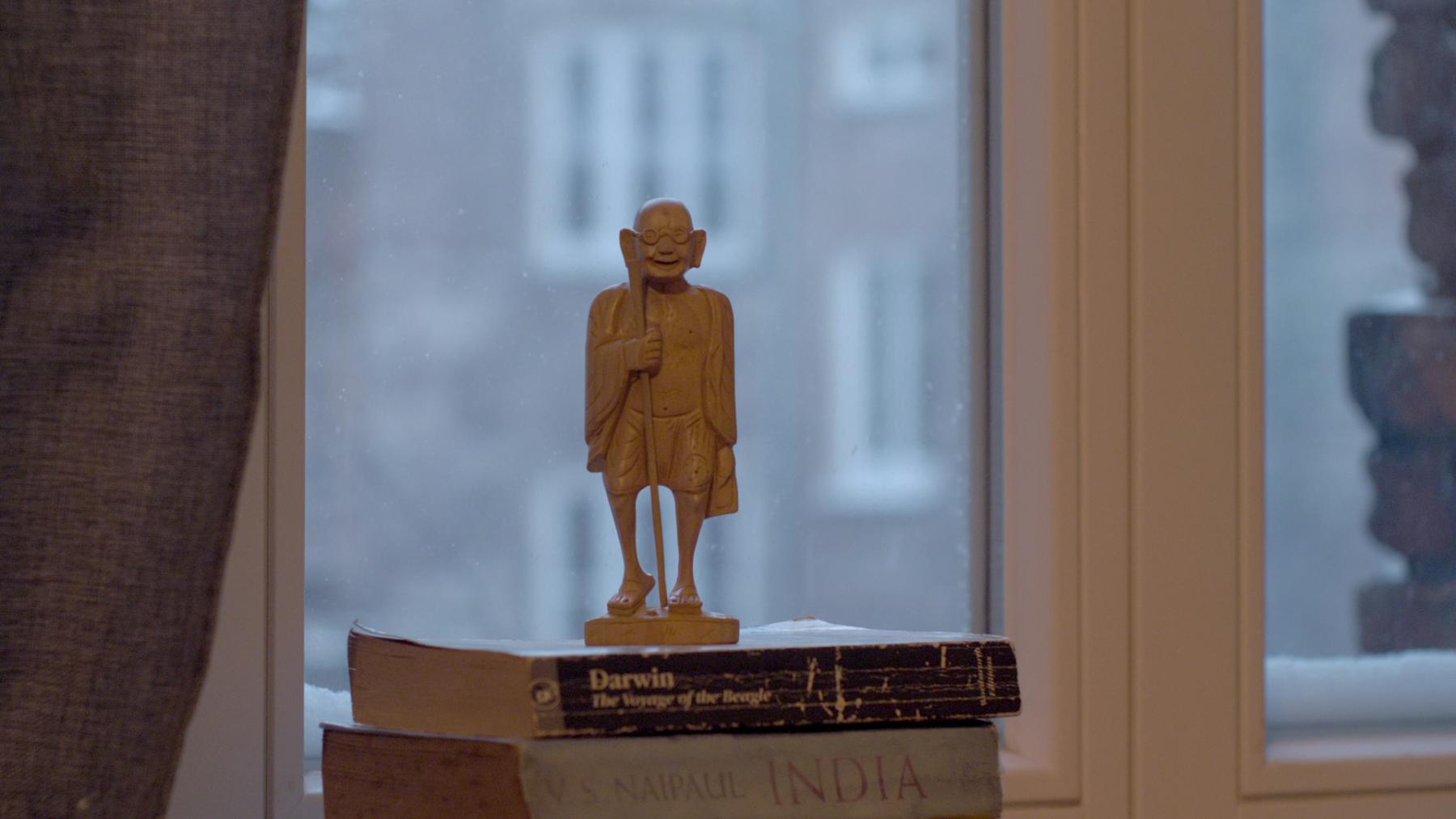

The protagonist was born to an upper-middle-class family in Bombay at the heels of economic liberalisation. He grew up in an environment of patriotic zeal, believing in Gandhian ideals of democracy while speaking English at home to improve his free-market prospects. However, these values also belied the rising communal tensions that gripped the subcontinent. Not unusual for their socio-cultural location, the protagonist’s parents swept any link to political discourses under the carpet, where it became “impolite” to bring up related subjects at home.

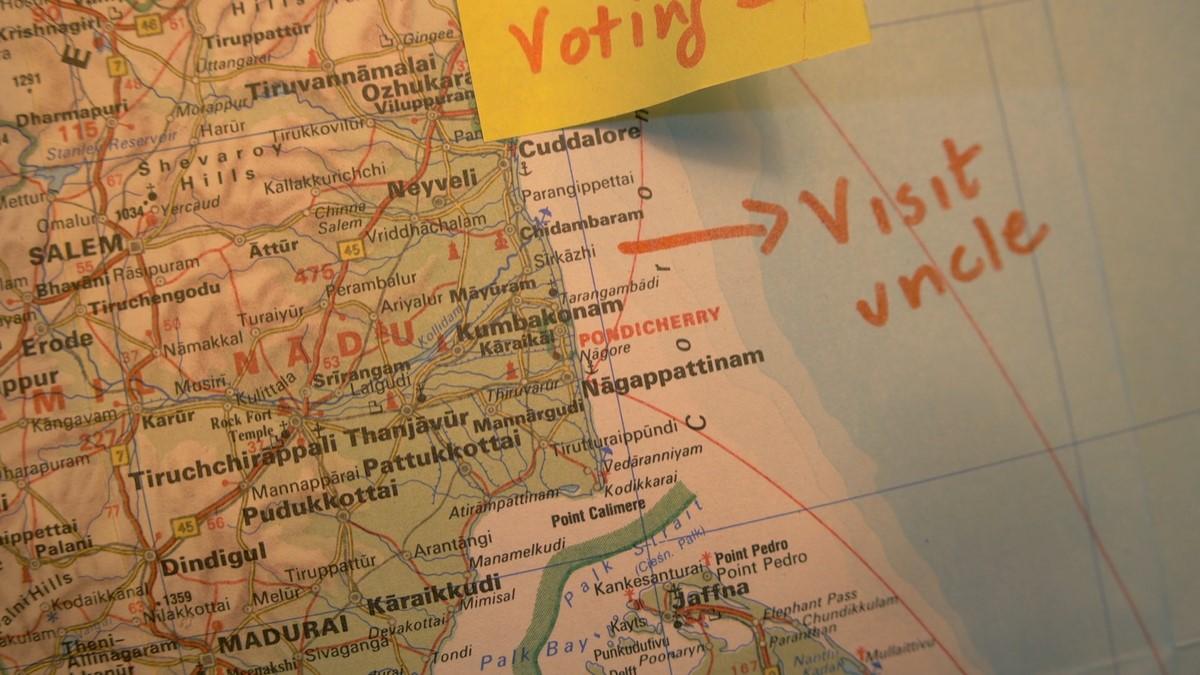

Later, the family shifted to the United States of America for their children's “fancy education,” and the protagonist eventually took up filmmaking in a European school. His yearly visit to India in 2019 coincided with the seven-phase elections, provoking him to re-examine his family’s relationship with the country’s political reality. Encounters with relatives and domestic workers throughout the filmmaking process unfurl divergent perspectives, betraying his parents’ complicity in the fantasy of India’s progress. The film persistently circles back to this domestic haven of wilful ignorance in an auto-ethnographic gesture.

In her research on the English-speaking urban dominance of the new middle class in the 1990s, Leela Fernandes notes the “politics of forgetting” vis-a-vis social groups marginalised by India's integration into global markets. It was not an inadvertent but an active political-discursive project that sought to construct a sanitised image of economic globalisation while naturalising its exclusions. New imaginations of citizenship emerged based on identitarian relationships with the state and capital. The corresponding construction of spatial purification further reinscribed communal divisions. Typifying this section of the upwardly mobile elite, the protagonist's parents in Don’t Worry About India act as constitutive agents in the marginalising of narratives.

The film maintains a bittersweet tone as the various subjects in the film vote in the elections that are held across different states. Their political behaviour often veers towards the comical but, at the same time, also displays dark underpinnings. From his golf-enthusiast uncle and the family’s caddy—who attends every political rally for a day’s wage—to another uncle, who has taken up the lifestyle of a farmer after leaving the army, the film plays out these dramatic tensions in an amusing way. Other intriguing characters organically cross the protagonist’s path, such as his mother’s school friend who now labours in their colossal farmland in the village or a fortune teller who comfortably predicts that those in power will get re-elected.

The film’s narratorial tone navigates these dramatic modulations remarkably. It registers requisite silence at poignant moments yet does not abstain from sarcastic remarks at the farcical comedy that occurs in the functioning of political parties. “I have found the spirit of democracy. It was brandy!” the protagonist remarks after learning how it is money, muscle power, and alcohol that help win elections. Though his political discoveries often appear facile and predictable, they mostly serve as catalysts for critiquing his extended family’s problematic heritage.

Don’t Worry About India posits a notable case of developing critique from situated knowledge—questioning the protagonist’s family's principles and orientations. There is a discernible shift in tone as the film proceeds through personal confrontations towards its culmination during the emergent moment of the nationwide CAA-NRC protests. Seemingly, the carved figurine of Mahatma Gandhi that he had carried to India assumes a caricaturish form in the last frame. Or maybe, it is the filmmaker’s altered perspective that permeates by the end of this exercise.

To read more about films screened at the Kolkata People’s Film Festival, click here, here and here.

All images from Don’t Worry About India (2022) by Nama Filmcollective. Images courtesy of the collective and Kolkata People's Film Festival.