The Afterlives of Images: Until the End of the World

Walking into the exhibition Until the End of the World, one is greeted by what appears to be a deceptively simple layout of six works on the four walls of the gallery space at PHOTOINK. Yet upon closer examination, one realises that artist duo Madhuban Mitra and Manas Bhattacharya are dealing with complex histories of technology, labour and capital spanning the history of film in the twentieth and twenty-first-century. Even as their works reference an archive of images, they speak to present concerns and the uncertainty of the future. Gleaned from over 10,000 films collected since the early 2000s from a large cinephile network, Madhuban and Mitra decided to “…photograph films as pre-existing representations of the visible world.”

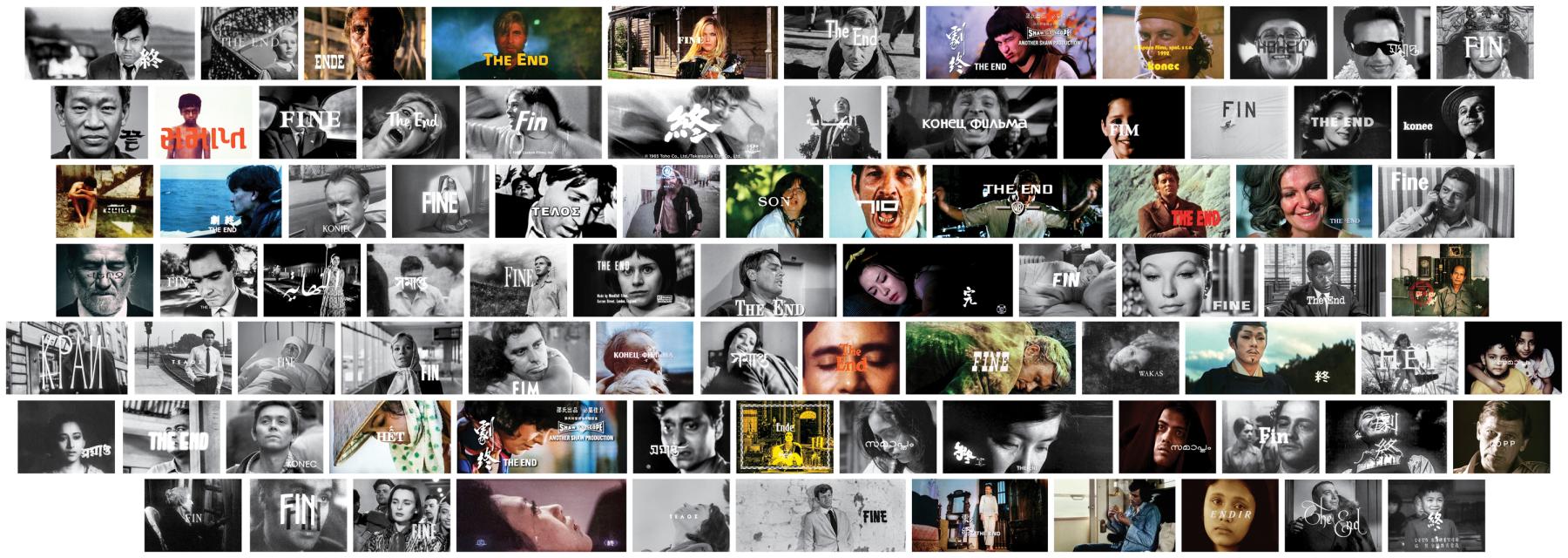

The Long Goodbye.

Conceived by the duo between 2019 and 2022, each work is presented as a grid containing stills in which the end credit sequence contains text accompanied by an image. These are ordered thematically to a large extent, as clusters of image data with variations of “The End” visible on them. The beauty of the series is in its use of the montage—through the juxtaposition and placement of text and image, of image and image, and between the texts. Each work plays with the idea of finality or an imminent end with reference to what is being represented. In this way, the artists play with compressed time and space within the filmic to think through the nature of experience. The work The Long Goodbye, consists of portraits as it juxtaposes faces that are known and unknown. Frozen in time, these faces capture a range of emotions that constitute the experience of being alive, even as we wonder about the possibility of death and that many of these people may not be alive today.

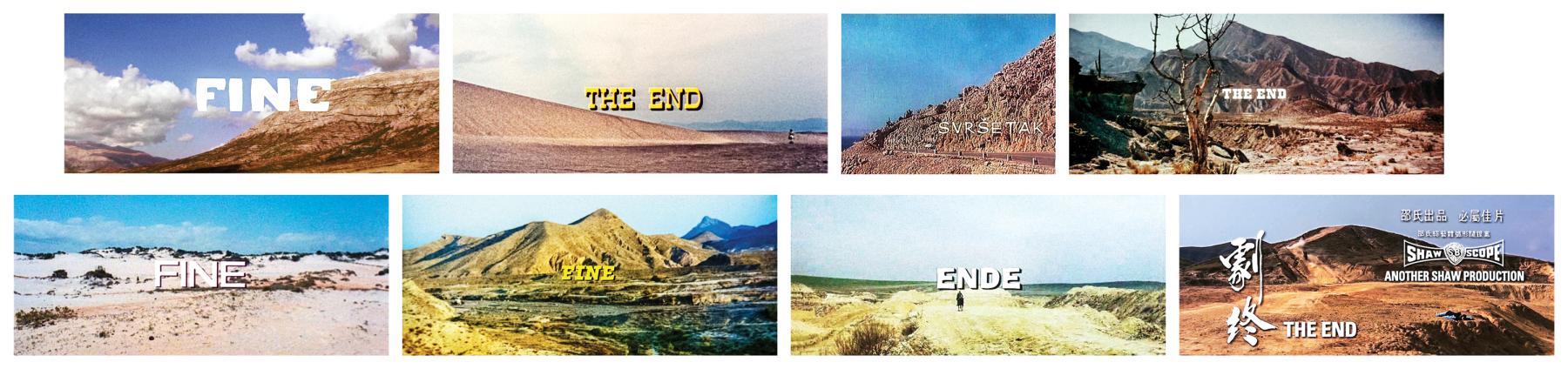

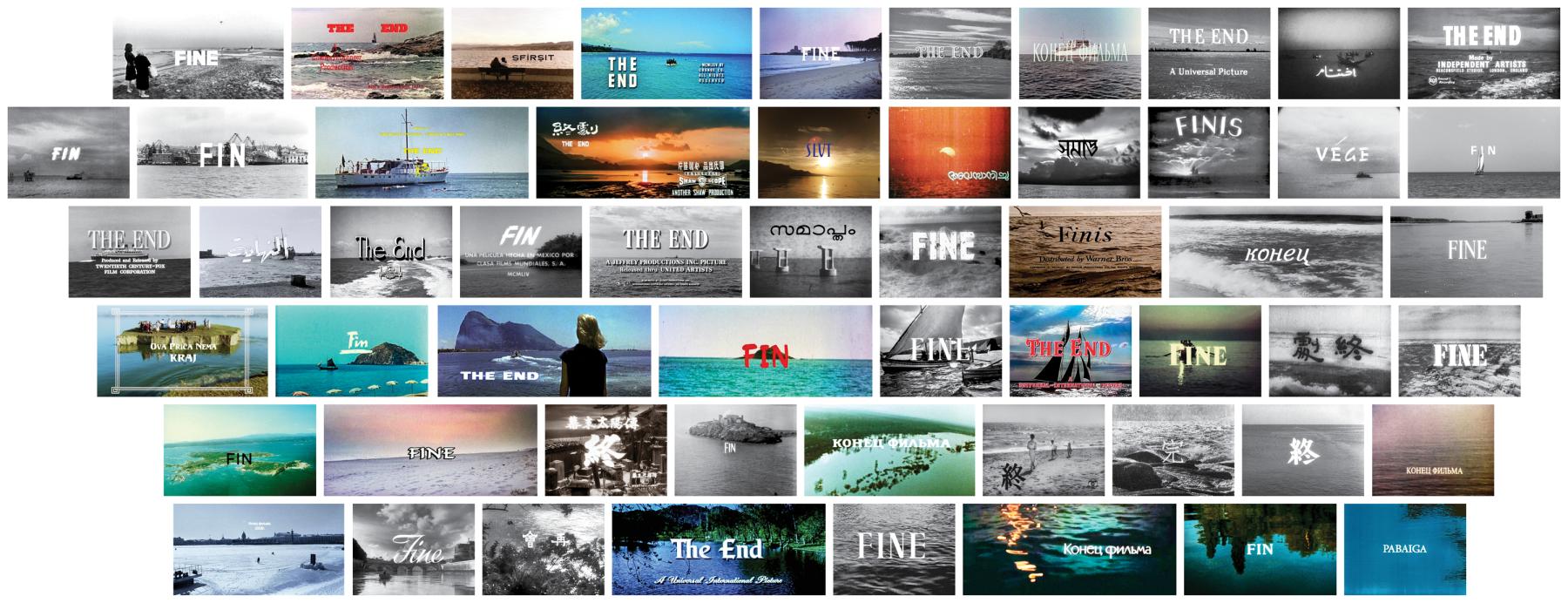

Intimations of an Apocalypse deploys the idea of doomsday in the anthropocene as translations of “The End” in various languages are overlaid on diverse landscapes from across the world. Speaking to this work and placed alongside it is Finis Terrae, which brings together various seascapes. The title is in Latin, and translates to “the end of the world,” and is perhaps also a reference to the 1929 Jean Epstein film by the same name. The two invoke an elemental logic where the surface of the earth is treated with a certain finality as the exploitation of our planet’s finite resources leads us to an inevitable end. Yet, the repetition in the titles also becomes a form of jest—despite our preoccupations with the idea of doomsday or the apocalypse as a trope, we continue to proceed in the same way as before.

Detail from Intimations of an Apocalypse.

In Borrowed Skies, different hues and cloud formations fill the frame, reflecting on how skies have been looked at in photography. Interestingly, the aeroplane appears in several of the end scenes, puncturing the shots and also hinting at the colonisation of the skies as new frontiers continue to be established. Mitra, in a conversation with the writer, mentioned that the title also acts as a key to the exhibition, as the artists are not making images but “borrowing” them. The act of re-photographing by the artists in order to re-use or re-purpose these images is a reminder that forms of meaning and production are not final. Unwitting Streets plays with this idea of the end through the implication of the open road—as a future filled with possibilities. The images are alike in their use of perspective, as the composition of the shots involves the use of the vanishing point, and an indication of the imaginary line that is understood as the horizon.

Of the six works on view, Endgame is perhaps the hardest to parse initially. The images are an eclectic mix with no immediate organising principle apparent on first viewing. Here, the writer had to refer to the title for some clue as the work references the idea of the chessboard, where language is the medium of play. The checkerboard format of the chess game is replicated through the alternating use of English and Italian in the titles “The End” and “Fine” respectively. Here, the artists critique monolingualism by signposting the Italian word “fine”, often misunderstood for the English word “fine”, to comment on the dominance of English as lingua franca.

Detail from Endgame.

The grid form allows for certain binaries or boundaries—such as those of nations/nationalisms and language—to collapse and be rendered meaningless. Yet other forms of hierarchies exist in the archive and the process of archiving. In a conversation with the writer, Mitra highlights the impossibility of containing everything within the archive, as there are always hierarchies to inclusion. While the digital realm has enabled people to access films much more easily, there continue to be hierarchies around film distribution. While pirate publics with their equalising nature have enabled a work like this to be made, the social construction of hierarchies forms a crucial node in how film history is encountered. Considerations of how closely film is bound with capital—which ultimately decides who gets access to watch or read without restriction—informed the series. Many production details are often visible in the stills, adding layers of information to how we read the labour and capital invested into making an image. The artists respond to this unevenness of the archive in a ludic manner. While Mitra and Bhattacharya derived images from a wide range of films from different countries, they have also surreptitiously inserted their own images within the grids. This intervention alludes to the mutating nature of film history, as films considered “lost” are often unearthed or rediscovered. One can also read forms of erasure in the archive through the inclusion of end credit images from several Films Division films, bringing to mind the recent closure of the film body as an autonomous unit.

Detail from Unwitting Streets.

Working within media archaeology as practice, the act of re-photographing becomes an interesting intervention on the part of the artists. In their statement, the duo write that re-photographing allows them to “…freeze, fix (to use a photographic term) and give material form to what was ephemeral, and to isolate an image from the continuum of the film.” Yet, this act of photographing is not the final conclusion. Rather, it becomes an act of translating a moving image into a still one. Existing in the blurred lines between photography and cinema, Until the End of the World opens up film language as a fluid and playful expanse even as it comments on circuits of power and representation.

Finis Terrae.

To read more about the IAF parallel shows, click here, here and here.

All images from the series Until the End of the World (2019-2022) by Madhuban Mitra and Manas Bhattacharya. Images courtesy of the artists and PHOTOINK.